A Life in Livres

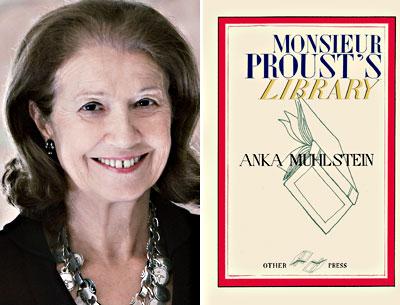

“Monsieur Proust’s

Library”

Anka Muhlstein

Other Press, $19.95

Anthropologists have suggested that societies without writing have a linear sense of time, while in literate societies the sense of time is cumulative. It stands to reason, then, that the great novel of the last century, with its accumulative thrust and ruminations on the past, was also a book about, well, books.

Perhaps nowhere more than in “In Search of Lost Time” are literary tastes so paramount to defining character. Next to art, childhood, homosexuality, love, memory, and society, the central themes of Proust’s novel are manners and aesthetics. Throughout the novel, characters reveal themselves by what and how they read. The bookish Bloch falls in the narrator’s estimation when he hastily dismisses the work of Racine and Ruskin, while the Duchesse de Guermantes bares her genius by using literature as “a wonderfully subtle social instrument of domination,” invoking Darwin to dazzle her dinner guests and reciting Victor Hugo’s poetry to best her husband’s poorly read mistress.

Like “Balzac’s Omelette,” her lighthearted study of the impact of gourmandizing on Balzac’s oeuvre, Anka Muhlstein’s latest work of literary investigation, “Monsieur Proust’s Library,” is a concise, accessible affair — part biography, part criticism — that examines “In Search of Lost Time” through the lens of its author’s reading mores. Despite the book’s brevity (it runs to 129 pages), Ms. Muhlstein covers a large canvas, drawing a portrait of the artist as a young reader and disclosing some of the ways Proust absorbed literature into his final masterpiece.

Arguably the most interesting sections of “Monsieur Proust’s Library” are devoted to those immediate predecessors Proust admired with reservations: Balzac and Ruskin. Ms. Muhlstein points out several lightly veiled Ruskin appearances in the novel: How his theory that beauty resides in “the simplest objects” is parroted in Proust’s novel by the painter Elstir; how the book the narrator falls asleep to in the novel’s opening may be Ruskin’s “The Bible of Amiens”; how “sesame,” the password to gain entrance to the male brothel, is a comical allusion to the fastidious art critic’s book “Sesame and Lilies.”

More important, Ms. Muhlstein convincingly argues that Ruskin provided the young novelist with a sense of architectural design. Proust spent nine years translating — or polishing his mother’s translations of — Ruskin’s works, and, although his enthusiasm for the English critic waned over time, what he learned in the process was profound. Proust’s introduction to Ruskin’s “Sesame and Lilies,” which Ms. Muhlstein quotes from, speaks volumes about the construction of “In Search of Lost Time”:

“Ruskin arranges side by side, mingles, maneuvers, and makes shine together all the main ideas — or images — which appeared with some disorder in the course of his lecture. . . . But in reality the fancy that leads him follows his profound affinities which in spite of himself impose on him a superior logic. So that in the end he happens to have obeyed a kind of secret plan which, unveiled at the end, imposes retrospectively on the whole a sort of order and makes it appear magnificently arranged up to this final apotheosis.”

As for Balzac, Ms. Muhlstein illustrates how, despite Proust’s reservations about the French author’s inelegant style and excessive explanations of his characters’ feelings, Balzac’s work may have paved the way for the more cautious Proust to write openly about homosexuality. Proust, Ms. Muhlstein writes, “reveled in Balzac’s boldness” and morally neutral exploration of homosexual themes. One of Balzac’s inventions, the escaped convict Vautrin of “The Human Comedy,” gave Proust a model for his own mature homosexual character, the Baron de Charlus.

“Monsieur Proust’s Library” is an agreeable addition to the growing list of original books about “In Search of Lost Time,” such as Alain de Botton’s “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” Eric Karpeles’s “Paintings in Proust,” and Phyllis Rose’s “The Year of Reading Proust.” Like Mr. de Botton’s charming, irreverent book, which draws a convincing portrait of Proust in the guise of a self-help book, “Monsieur Proust’s Library” pursues serious scholarship while remaining genial to the lay reader.

Yet the risk of such books is that one reader may want for more academic rigor where another wants for more levity. Ms. Muhlstein’s suggestions about Proust’s methods and motives, about the books that shaped his characters, are thought-provoking. They are also, occasionally, mundane. Strangely enough, for a book this short, one wishes that an editor had actually excised a few of the sentences, especially those attesting to the obvious: that books mattered a lot to Proust.

Will Schutt won the 2012 Yale Younger Poets Prize. His poems and translations have appeared in The Southern Review and A Public Space, among other journals, and he has a collection, “Westerly,” due out in April. He lives in Wainscott.

Anka Muhlstein lives part time in Sagaponack.