Lighthouse Is Now A Landmark

On Monday, the Department of the Interior officially designated the Montauk Point Lighthouse a national historic landmark.

It took the advisory board of the agency’s National Park Service six years to study the application submitted by the Montauk Point Lighthouse Museum.

“It’s great. The designation will be a financial advantage,” said Brian Pope, the museum’s assistant site manager. He explained that grant proposals, for instance, might be given a priority as well as help in the event of damage from a monster storm or other calamity. He said a celebration would take place sometime next summer.

The Lighthouse is the 12th national landmark on Long Island. There are only 2,500 in the entire country, one of which is the Old Whalers Church in Sag Harbor, and two of which are in the Town of East Hampton — the Thomas Moran House on Main Street in East Hampton and the Pollock-Krasner House on Springs-Fireplace Road in Springs.

The Montauk Point Lighthouse was commissioned by President George York City Chamber of Commerce going back to 1792 to show the dominant role the Lighthouse played in both pre- and post-Revolutionary War trade between New York and England.

Specifically, Mr. Hefner was able to show that the Light’s position relative to the prevailing winds made the landmark vital to navigation in the age of sail up until the time when steam-powered vessels were deemed trustworthy enough to ply a direct course to New York Harbor.

By the time the Montauk Lighthouse was built, New York Harbor was handling a third of the nation’s trade with other countries. According to the city’s 1870 commerce and navigation report, 75 percent of all goods imported from Great Britain and 89 percent of all goods from France — a total of 44 percent of all American imports — entered this country through New York Harbor following the same sea routes protected by the Montauk Light.

“Bob Hefner was one hell of a detective,” Mr. Pope said, adding that Eleanor Ehrhardt, a member of the museum’s Lighthouse committee, “spearheaded the process.”

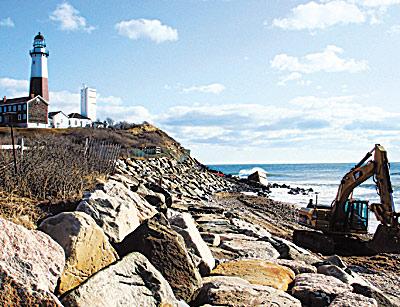

Work began this week to buttress and repair the southwest portion of the stone revetment that protects the new national landmark.

Greg Donohue, a committee member and expert on shoreside erosion control, said the work, being done under a permit from the State Department of Environmental Conservation and the Long Island State Parks Department, was to repair a settling, or “slump,” in the existing revetment that occurred during the last year in the area behind a concrete structure known to surfers as the Alamo.

The structure was a World War II-era fire-control bunker that years ago fell because of erosion from the top of Turtle Hill, as the Montaukett Indians called the bluff on which the Lighthouse sits.

Mr. Donohue said that a level of boulders was being added to about 140 linear feet of revetment on the Turtle Cove side to bring its height up to 19 feet above sea level in keeping with the height of the stonework that rings the sand and clay Lighthouse bluff.