Links Life

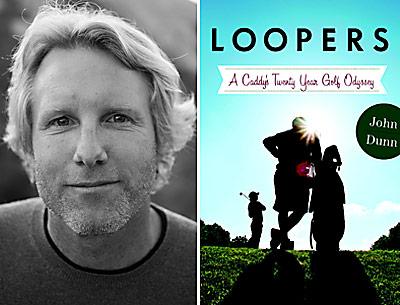

“Loopers”

John Dunn

Crown, $25

Sometimes it takes an outsider to really appreciate a place. Remember Maycroft? That immense hulk of a mansion that for years loomed over North Haven in glorious Miss Havisham decrepitude? Though it was bought, entirely renovated, and hidden away behind gates, it may linger in the popular consciousness here as the former home of a private school for girls and then the Rainbow Preschool. But who knew one wing once housed a bunch of itinerant caddies?

John Dunn recalls it fondly in his new book, “Loopers: A Caddie’s Twenty-Year Golf Odyssey.” He does more than recall it. He brings it back to life with an account of evenings of play on a wedge course he fashioned on the property’s 40 acres, run at the time by an order of Episcopal nuns: “. . . down past the dilapidated teahouse, all overgrown with honeysuckle and ivy, to the weathered, warped, clamshell-littered dock, and finally back up the hill past the huge elm to the row of gravestones beside the house where the sisters were all buried, including the mother superior, whose headstone became the eighteenth hole.”

At one point he and a personable caddie from Ireland motor a borrowed boat into Sag Harbor, pick up a couple of girls at a bar, go skinny-dipping with the cove’s phosphorescent jellyfish, and take the two back to Maycroft for sex beneath the religious relics. It’s nice to know the place knew such joy.

These were the years 1999 to 2001, and Mr. Dunn was working at the Atlantic in Bridgehampton, standing out as a white guy in a caddie yard full of Jamaicans and Antiguans known on occasion to leave a burning spliff on the fairway. And in case you’re thinking caddying is mere menial schlepping or kid stuff for losers and lost souls, at the height of the season, from mid-August to Labor Day, they each pulled in $500 a day, easy — to say nothing of the requisite expertise in yardages adjusted for wind and elevation, how to read a green, club and shot selection, and the psychology of sports.

You might say a looper is a veteran caddie, but Mr. Dunn puts a finer point on it: “A looper isn’t a caddie who’s seen it all; a looper is a caddie who’s seen enough to know he never will.”

But that doesn’t stop them from trying. In Mr. Dunn’s case, his career takes him from his home in Connecticut to crisp Aspen, Colo., to the gators of South Carolina’s Lowcountry to the California high desert and on to the whispering pines of Georgia’s storied Augusta National. One particularly memorable trip traces 3,500 miles from the Baja Peninsula up the West Coast to British Columbia. He hitchhikes across Utah, Arizona, and Nevada on his way to San Francisco with a sand wedge strapped to his pack to play some backcountry golf en route.

At a marina and restaurant on the Intracoastal Waterway in Beaufort, S.C., he befriends a couple in the midst of a round-the-world sail and comes to see his adventures as akin to theirs: “I liked that romantic vision of caddying as a vehicle that carries you to beautiful far-flung places, the golf courses like ports where you dock for a while, fix your sails, replenish your supplies, and then set sail again the following season for another destination.”

Metaphor made manifest, he later meets one of his brethren who actually lives on a sailboat, albeit one that’s permanently trailered and towed around to campgrounds across the country.

No amount of perambulation, however, can outdistance the disapproving gaze of his father, who, whatever the adventure recounted, responds with an inquiry as to his son’s real plans to settle down and start a life. He’s a strait-laced sort prone to exclamations like “Darn tootin’!”

“I’m not quite sure what he’d visualized a caddie’s role to be,” Mr. Dunn writes, “perhaps something like a bellhop or a waiter.”

That assessment joins wanderlust in dogging the author. It’s driven home to devastating effect when, in chatting up a woman in a Venice, Calif., bar, he relays what he does for a living and she answers, “You know, you really shouldn’t tell people that,” before moving on to talk to someone else.

Here’s one answer to the ghosts that haunt him. Back on the South Fork, we find Mr. Dunn caddying at Shinnecock Hills, a “once-in-a-lifetime experience” at “arguably the finest course in the country.” One quiet Monday at the close of the season he and his friend Carlo tee off next door at the National Golf Links of America and after the first nine holes hit their balls from 10 over the trees onto Shinnecock’s third fairway, play on, and then when they again reach Shinnecock’s third they cross back over to finish out at National. They call the hybrid course the Double Helix — “quite possibly the greatest contiguous thirty-six holes in the world.”

“This is why we can’t quit caddying!” Carlo says from a bluff above Peconic Bay as the setting sun turns the world a molten gold.

Throughout, Mr. Dunn is an eminently likable, self-deprecating tour guide with a knack for descriptions of nature and setting, from a Los Angeles that’s “all hell and smog” to St. Andrews in Scotland, where he plays a nighttime round by himself in a fog as thick as a blizzard’s whiteout.

His book is full of loops within loops. That round in the Scottish “haar” recalls his golfing in the dark when he was young. He hitchhikes around the country more than once. He starts his tale in Connecticut, glad to stay away for years from perhaps our least interesting state, and then returns at last, wisely avoiding any “knowing the place for the first time” cliché.

Mr. Dunn does settle, in a way, becoming a writer, a career no more reputable than caddying, when you get right down to it. The point is moot with his father, as he had developed pancreatic cancer. Their decades’ distance is finally, forcibly broken when Mr. Dunn sits bedside and won’t leave even when his father clearly doesn’t want to talk. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.

John Dunn has written for The Golfer and Travel + Leisure Golf magazines. He lives in Southern California.

The National in Southampton will host the 2013 Walker Cup from Sept. 6 through Sept. 8.