'Listening to Marlon Brando' Is Latest HIFF SummerDoc

The second film in the Hamptons International Film Festival’s SummerDocs series, “Listen to Me Marlon,” has no talking heads, no interviewees, no narrator. With the exception of a few television news clips, the voice on the soundtrack is Marlon Brando’s, and it affords access to the actor’s multidimensionality seldom available even to his friends.

John Battsek, a producer at Passion Pictures in London, was approached by the Brando estate, which was interested in supporting a documentary to mark the 10th anniversary of the actor’s death. Mr. Battsek invited Stevan Riley, an English filmmaker with four documentaries to his credit, to undertake the project.

“We knew the estate would approve the documentary and give us access to the archive,” said Mr. Riley, who wrote, edited, and directed the film. “But it wasn’t yet determined what was in the archive and how much there was. It turned out there were reams and reams of documents, some home movies, and there were these tapes.” “These tapes” were approximately 300 hours of audiotapes made by Brando that nobody, not even managers of the estate, had heard.

“I was given a selection that had been digitized, seven or eight tapes, and I was lucky they happened to be really interesting. They included a self-hypnosis tape, and I started trying to figure out an approach and thought how bold it would be if we could tell something entirely in Marlon’s own words.”

Initially, Mr. Riley wasn’t sure his idea would work. He came to the United States from London to interview as many people involved in Brando’s life as were available to him — his family, work colleagues, friends, and personal assistants. “The further I got into speaking with these people, the more I was inclined to stick with my original plan, doing it all in Marlon’s voice, because he kept his life so compartmentalized that there was no one who could give the whole picture. I thought, who better to give that full picture than Brando?”

As more and more tapes were coming out and being transcribed, Mr. Riley realized his idea for the film was doable.

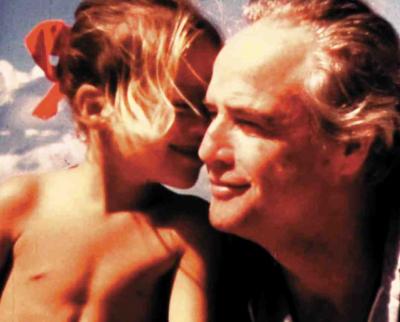

Brando’s ruminations, recorded in the solitude of his home on Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles, range from reflections on his childhood, particularly his troubled relationship with his father, to the many phases of his acting career, his eventual aversion to fame, his political involvement with the civil rights movement and Native American activists, his relationship to his children, and his growing seclusion. Personal photographs, clips from home movies, and archival news footage, like the audio recordings, move back and forth in time, creating an increasingly layered impression of the inner and outer man.

The self-hypnosis tapes are especially moving, and one, from 1996, gave rise to the film’s title.

“Listen to Me, Marlon. . . . This is one part of yourself speaking to another part of yourself. Listen to the sound of my voice and trust me. You know I have your interests at heart. . . .”

Brando’s sense of humor is as present as his insightfulness. In one segment, perhaps from a home movie, he makes a series of funny faces that are almost impossible to reconcile with Brando the icon. Elsewhere he says, “If I hadn’t been an actor, I’d have been a con man.” He discusses how during the 1930s and 1940s “you knew what you were getting from the actor — the same thing each time. Stella [Adler] changed all that.” Though seldom satisfied with his work, his aim was “to make it as real as you can, to find the truth of that moment. When it’s right you feel it in your bones.”

Regarding the self-hypnosis tapes, Mr. Riley said, “I wasvery aware of how private he was, and I wanted to protect that in some regard. The way to do that was to make sure I was as well informed as I could be so that I could portray him in as honest a way as possible. He thought he had been misrepresented so often that I thought the tapes offered a way he could explain himself that he had never been allowed as a public figure.”

Brando had his face digitized in the 1980s by Scott Billups, a digital filmmaker who, years later, tracked down the original files. Working with Mr. Riley, Mr. Billups and his team used the files to create an animated 3-D version of the actor’s face, which appears as an overlay in shots of the interior of Brando’s home.

“I always wanted to put those images in the house as a ghostly presence, as if he was giving a postmortem of his life from beyond the grave.” They do indeed leave the impression of Brando hovering over the entire enterprise, keeping his eye on the filmmaker and his audience.

A discussion between Alec Baldwin, and Mr. Riley will follow the screening Aug. 1 at 8 p.m. at Guild Hall. The film will have its theatrical release on Wednesday, at Film Forum in Manhattan, and on Friday, July 31, at the Landmark in Los Angeles, before rolling out nationwide throughout the summer and fall.