The Long Habit of Living

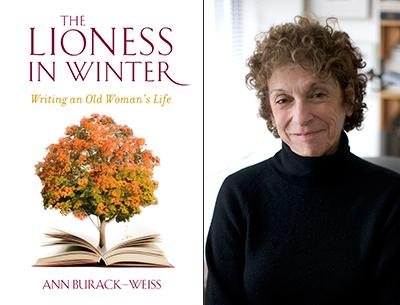

“The Lioness in Winter”

Ann Burack-Weiss

Columbia University Press, $30

“There are compensations for every decade,” my grandfather used to say, casting the specter of aging in a positive perspective. As I reach for reading glasses or cantilever myself into a yoga position, my grandfather’s words sometimes return to me. I count my compensations gratefully. Why, just last week, a miracle: I risked telling a joke at a dinner and delivered the punch line intact. In exchange for failing knees, I reason, the reward has been a little hard-won social confidence.

In the famous arrogance of youth, old age is the shore we’ll never reach. As the decades pile up, we vow to stay always connected and relevant. We choose the voodoo of healthy living to ward off illness and injury. But “age trumps all,” writes Ann Burack-Weiss in her elegiac new book, “The Lioness in Winter: Writing an Old Woman’s Life.”

“Old age is terminal,” in the words of Doris Grumbach, now nearly 100, whom Ms. Burack-Weiss quotes, “but still, I find the long habit of living hard to break.” Indeed, as they say, it’s better than the alternative.

A social work practitioner and educator, Ms. Burack-Weiss staked her claim on the field of gerontology in 1969, in grad school, to which she returned after her second child started school. “It was a heady time for social work education at Columbia University,” she reports. The “war on poverty” was on. Money available for social programs was substantial. Yet, the view that “there was nothing you could actually do with, or for, the old” prevailed. Who could picture the vital student protesters who took over Low Library as old, much less depleting the coffers of Social Security and Medicare?

Ms. Burack-Weiss claims her career choice was counterphobic. “I became a social worker with the aged because I was afraid for my life,” she confesses. “I was packing a virtual doomsday kit — shoring up resources of information and insight to sustain me when I became one of them.”

However, data on the aging was virtually nonexistent at the time. The evolving field of gerontology — to the author’s dismay — was increasingly objectifying the aged into “activities of daily living” assessment lists matching needs to services. In a quest for information from the front, Ms. Burack-Weiss obsessively read the memoirs of women who had grown old in print.

Nearly five decades later, the author has put a lifetime of musings into “The Lioness in Winter,” a slim and beautiful volume that is part memoir, part career-confessional, but most compellingly a collection of writings on aging from women she admires.

The professional, she owns, has lately become personal. Widowed now and in her late 70s, Ms. Burack-Weiss finds that her life is circumscribed by a fall in which she broke her pelvis. Through this book, she is teaching what she still needs to learn, she writes. Her companions are, most recognizably, Doris Lessing, Edith Wharton, Joan Didion, Maya Angelou, and Colette, among many others whose thoughts on aging will most certainly be new to many readers.

Originally Ms. Burack-Weiss intended to create a kind of “verbal version” of the artist Judy Chicago’s iconic mid-1970s piece “The Dinner Party,” which was a table with individualized settings for 39 women who advanced women’s causes. Ultimately, though, Ms. Burack-Weiss felt she wanted to reveal the influence of each writer in a far more personal way.

The outcome, she admits, is “a highly idiosyncratic collection,” a kind of conversation in which her thoughts are processed on the page, along with those of others. The messages are often grim. The kinds of compensations my grandfather promised are very few. The truths delivered are exactly those that make the subject of aging so unpopular: physical pain, dependence, diminishing capacities — or, if not that, then a growing sense of becoming marginalized.

“Old age is a little like dieting. Every day there is a little less of us to be observed,” wrote Ms. Grumbach nearly 20 years ago. “It differs from dieting in that we will never gain any of it back.” Reading these words, it’s hard to know whether to laugh or cry.

But then there is Edith Wharton’s generous optimism: “In spite of illness, in spite of the arch-enemy sorrow, one can remain alive long past the usual date of disintegration if one is unafraid of change, insatiable in intellectual curiosity, interested in big things and happy in small ways.”

Ms. Burack-Weiss has categorized her “personal stars” by the eras in which they were born, although time, except for its inevitable passing, is not significant. On the universal subject of aging, the voices of Gerda Lerner or Vivian Gornick, while individual, speak as one. I confess I would have liked more biographical information on a few of the women who are lesser known. I can appreciate, however, that the author may have chosen not to identify her literary companions by the achievements that defined them at the peak of their lives.

If I had a quibble, it’s that “The Lioness in Winter” fails to launch until page 43, which in a book of 160-odd pages feels significant. Is a chapter that identifies and describes the differences between autobiographical forms (i.e., memoir versus journal entry) truly needed? The lesson feels tacked on, more suited to a college freshman English class.

At that point I began to worry that the book was an analysis of memoirs about old age in which we’d never get a taste of the original material. I rifled ahead to see what was in store.

Thereafter, though, the narrative takes off. Its broad areas of preoccupation are those that consume us all: body, identity, home, sex, death, and happiness — occasionally even shopping. “I greatly enjoy making out checks and spending money in every possible way,” wrote (or perhaps dictated) May Sarton in talking about small pleasures in her journal before her death at 83. “This is not only true of my old age; it has always been true,” she confessed.

Ms. Burack-Weiss wonders what she or anyone can offer younger, more able people who assist the elderly, and this is followed by a description of her encounter with a drugstore attendant who has happily helped her assemble a blood pressure monitor that is beyond her capabilities. I love her answer. Maybe like Lear’s Cordelia, she concludes, she is “herself a dowry.”

“The Lioness in Winter” is a follow-up to Ms. Burack-Weiss’s “The Caregiver’s Tale: Loss and Renewal in Memoirs of Family Life.” In both books, the work of Joan Didion acts as a kind of divining rod. “I protested her view of the aging female experience,” Ms. Burack-Weiss writes of reading “Blue Nights,” Ms. Didion’s bleak 2011 memoir about her regrets and fears of declining powers. “So hard did I protest that it would not take the insight of Shakespeare or Freud to recognize that I protested too much.”

Indeed, I myself approached “The Lioness in Winter” with one eye closed, at first resisting its more difficult truths. My objections are emphatically recorded in the margins of my copy — “No!” “Really??” “Unnecessarily negative?” But the author’s goal is not to sugarcoat the subject. After a while I stopped resisting, and the words began to resonate.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” she notes that Ms. Didion observed. Ms. Burack-Weiss appears to have followed her own advice: “It is what it is. Get used to it. And, if you’re able — turn it into art.”

Art abounds: in Edna O’Brien’s description of home in the “lambent light of that August evening, with the sun going down, a bit of creeper crimsoning and latticed along an upstairs window . . .” Or M.F.K. Fisher’s passage declaring that she was “completely sexually alive” for the husband who had died more than 40 years before.

I loved this bit of drama from Diane Ackerman: “I may not live to the end of this sentence, to lift my felt-tipped pen and settle a tiny black dot on the page. I did. But that was then and this is now, the thisness of what is, the ripening dawn.”

No slouch herself in the writing department, Ms. Burack-Weiss admits that in assembling her doomsday kit decades ago she had “packed sneakers to climb Mount Everest.” At base camp she has now gathered her friends, who tell her to love what is, find happiness in the everyday, show up for yourself, accept the kindness of strangers willingly — not new ideas, exactly, but newly inspiring in this context.

Ellen T. White is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” an exploration of the great romantic women of history. She lives in Springs.

Ann Burack-Weiss spent summers and weekends in Montauk from 1974 to 2011.