Long Island Books: All in His Head

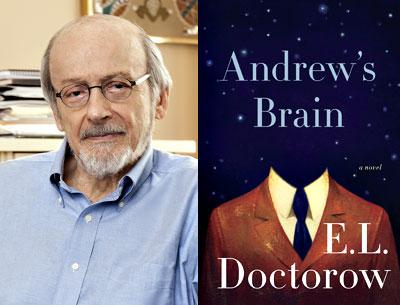

“Andrew’s Brain”

E.L. Doctorow

Random House, $26

The casual reader may be a bit surprised coming to E.L. Doctorow’s latest novel, “Andrew’s Brain,” not to find a story imbued with historical detail. The general perception of Mr. Doctorow is as a writer of historical fiction — even if this is a misleading delimitation — thanks to the sweeping historical canvases found in such works as “The Book of Daniel,” “Ragtime,” or “The March.”

More often than not, Mr. Doctorow’s primary concern is with his characters’ intersections (a word Mr. Doctorow himself has used) with history, the truer emphasis being on individual struggles for equilibrium within the American experience rather than simply the historical framework per se. We see this in “Homer & Langley,” in which he constructs a story of human frailty, compulsion, and alienation against the evolving milieu of early and middle-20th-century New York City. That struggle for equilibrium, less the overt historical context, is again at the forefront of his most recent work.

“Andrew’s Brain” has one of Mr. Doctorow’s simpler plotlines. Andrew, who describes himself as a “freakishly depressive cognitive scientist klutz,” is having a rambling conversation, almost a monologue, with another person. This person may be his therapist or a doctor of another sort or, possibly, neither. Perhaps Andrew is really only talking to himself. In any case, locked away at an undisclosed location (whether asylum, within his own head, or still elsewhere) he relates the story of the tragic effects he seems to precipitate upon others as well as himself — divorce, the death of his first child, the death of his second wife, the abandonment of their child.

Rather than emphasizing the outward struggle with the external world that the historical framework facilitates, “Andrew’s Brain” is more concerned with mapping an intense inward struggle concerned with loss, memory, and identity. As a cognitive scientist, Andrew knows, to a degree better than most, the science of how the brain works. He struggles to understand how his brain reacts to what has happened around him and to him in terms of that science. His own life becomes the subject of his analysis as a cognitive scientist. What is the relationship between what he knows objectively as a scientist about how the brain functions and his own individual experiences?

His very knowledge of the brain is a burden to him, however, as he tries to come to terms with what he has done and experienced and to find meaning within the resulting chaos. Despite all that has happened to him, Andrew is battered more by the limitations and perplexity of his own mind than the outside world. While trying to understand his relationship to the events surrounding him, he is constantly attempting to accept how his own mind works. How does the brain become the mind? When does it become the me? What is the difference, if any, between the brain, the mind, and the soul?

His brain is something he cannot escape: “It’s a kind of jail, the brain’s mind. We’ve got these mysterious three-pound brains and they jail us. . . . I’m in solitary. . . .” If he can simply understand and apply the science of it, he believes he can better endure the pains of his life and find some solace.

The narrative structure reflects his struggle and confusion as Mr. Doctorow places the reader into Andrew’s tormented and self-loathing mind. Andrew spews out whatever is within his head at the time, creating a mixture of memories, visions, and thoughts, so the story jumps from point to point, event to event, and back again. Occasionally, Andrew even shifts to the third person in telling his story, emphasizing the distance he tries to achieve from himself as he examines his own life.

At one point, he asks his listener if he is a computer, but he knows the brain is more a dynamical system than a computational one. Grappling with the processes that are a part of that dynamic system — memory (and forgetting), perception, reasoning, and understanding — creates a tension within his brain that becomes the story. But that very tension and struggle make everything that Andrew says questionable. What actually has happened and what is real only within Andrew’s brain? Whomever he is speaking to continually asks: “This was not a dream?” “Did this really happen?” “Do you think . . . you may sometimes overreact?”

History does intrude in the last third of the book — the least successful part of the story — with the 9/11 attacks and, more pointedly, a slightly comic introduction of an unnamed President George W. Bush as Andrew’s former Yale dorm roommate, and Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld, here named Chaingang and Rumbum. Andrew is appointed head of the Office of Neurological Research in the White House basement in order to have him sign a confidentiality agreement ensuring that there will be no politically embarrassing stories of the president as a Yale frat boy.

Mr. Doctorow’s prose is lean and honed to the essential, and there are more than a few pleasures found in the writing itself. His description of traveling north on I-95 is evocative and depressing at the same time (as well as somewhat apocalyptic). “I remember coming up the Jersey Turnpike, past the oil refinery burn-offs, and with the growling of the convoying semis in our ears, and away off to the left the planes dropping to the runways of Newark Airport and then the fields of burned grass irrigated by rivulets of muck and with what looked like a buzzard floating over the turnpike risen now on concrete pillars that in their tonnage were holding up the furious intentions of traffic, the white lights coming toward us, the red lights beckoning. . . .”

And he provides a poignant description of Mark Twain in his later years as he “rages at the imperial monster he has helped create.” “I see his frail grasp of life at those moments of his prose, his after-dinner guard let down and his upwardly mobile decency become vulnerable to his self-creation. And the woman he loved, gone, and a child he loved, gone, and he looks in the mirror and hates the pretense of his white hair and mustache and suit, all gathered in the rocking-chair wisdom that resides in his bleary eyes.”

There are also a number of small, neat comic touches, such as a scene of Andrew’s former wife’s husband, an opera singer, referred to by Andrew simply as Martha’s “large husband,” drunk in his living room and dressed as the titular hero of “Boris Godunov.”

Despite these fine moments, “Andrew’s Brain” is not major Doctorow; ultimately, the sum is less than its parts. However, even lesser Doctorow is worth more than the best of many other writers. Andrew’s philosophical, psychological, and scientific ruminations raise challenging questions about the process of knowing and the creation of the self, even if neither he, Mr. Doctorow, nor anyone else can provide satisfying answers.

After teaching literature at Southampton College for 30 years, William Roberson now works at L.I.U. Post.

E.L. Doctorow lives in Sag Harbor and New York.