Long Island Books: Back to the Future

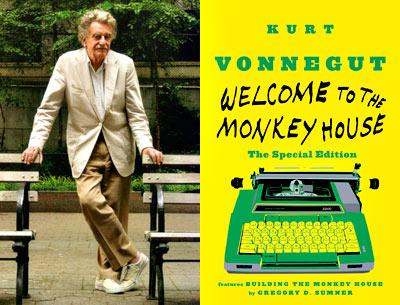

“Welcome to the

Monkey House:

The Special Edition”

Kurt Vonnegut

Dial Press, $18

The female praying mantis bites off its partner’s head during copulation. In the title story of “Welcome to the Monkey House,” Kurt Vonnegut introduces a biological paradigm in which the female entices men not to sex and death, but only death. The collection has just been re-released in a “Special Edition” edited by Gregory D. Sumner.

In the story, J. Edgar Nation is “the Grand Rapids druggist who was the father of ethical birth control.” Sickened by the sight of monkeys playing with themselves in the zoo, Nation runs home and develops “a pill that would make monkeys in the springtime fit things for a Christian family to see.”

“The only sexual beauty that an ordinary human can see today is in the woman who will kill him,” says Vonnegut’s character Nancy McLuhan, a hostess at one of the Ethical Suicide Parlors, which are Nation’s legacy. Nancy has been spirited away by Billy the Poet, who is out to change or restore the world to its former imperfection. Vonnegut’s dystopia is one in which an entity called simply “the World Government” controls world population growth by suicide or the administering of pills that kill all pleasure. “All the pills did was take every bit of pleasure out of sex.”

“Nothingheads” are the rebellious ones who refuse to commit suicide or take their pills, and it is they who spearhead the rebellion. Though the pain-pleasure principle may be manifested in different ways, the hyperbolically envisioned future is clearly a metaphor for the present. But no matter how outlandish the scenario, there is a frightful familiarity to Vonnegut’s creations.

“I’m not going to throw myself into your arms . . . and I’m not going to budge from here unless somebody makes me,” Nancy tells Billy as he prepares to initiate her into the world of pleasure. “So I think your idea of happiness is going to turn out to be eight people holding me down on that table, while you bravely hold a cocked pistol to my head — and do what you want.”

Even though Vonnegut’s character is a gargoyle, she’s complex and troubling and you believe her, just as you believe Herbert Foster, the central character of a story called “The Foster Portfolio.” Foster is a beneficiary of fortune who adheres to the notion that “every man, for his own self-respect, should earn what he lives on.” Vonnegut establishes his comic equation, as Foster works day and night to subsist while his fortune builds in his portfolio.

The comedy can hinge on something simple that catches the reader off guard because its nonsense makes so much sense, such as this about smoking, from Vonnegut’s preface to the collection: “The public health authorities never mention the main reason many Americans have for smoking heavily, which is that smoking is a fairly sure, fairly honorable form of suicide.” Vonnegut employs the understated reversal of Swift’s “A Modest Proposal.”

In “Report on the Barnhouse Effect,” about the title character’s paranormal ability to destroy weapons, the humor is stated thus: “But those who would make war if they could, in every country of the world, wait in sullen silence for what must come — the passing of Professor Barnhouse.”

Both the futurist and more quotidian stories share a prodigious believability. Vonnegut’s financial manager from “The Foster Portfolio” will startle readers because his outlook and strategies, conceived in 1951, when the story was published, remain on the mark even today. “My firm began managing Herbert’s portfolio, converting some of the slower-moving securities into more lucrative ones, investing the accumulated dividends, diversifying his holdings so he’d be in better shape to weather economic shifts — and in general making his fortune altogether shipshape. A sound portfolio is a thing of beauty in its way, aside from its cash value. Putting one together is a creative act, if done right, with solid major themes of industrials, rails, and utilities, and with the lighter, more exciting themes of electronics, frozen foods, magic drugs, oil and gas, aviation, and other more speculative items. Herbert’s portfolio was our masterpiece.”

Similarly, in “Deer in the Works,” Vonnegut shows a preternatural knowledge with his industrial juggernaut — the Ilium Works of the Federal Apparatus Corporation, “the second-largest industrial plant in America . . . increasing its staff by one third in order to meet armament contracts” — in which his central character, like the deer in the title, is momentarily trapped.

“The Lie” is a tale about the scion of a wealthy family who’s rejected from the elite prep school his forebears have attended. And it exudes a similar credibility in its picture of an upper-crust outsider.

Vonnegut was a satirist and fantasist who had one foot firmly planted on the ground — which is to say that while he may owe a great deal to futurists like Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, and Philip K. Dick, the sentiment, humanity, and complexity of his characters and the conflicts they endure also owe something to Balzac’s “Comedie Humaine” and Zola, in which complex individuals are the embodiment of equally complex social forces, like the close-to-home ones in the title fable.

And one of the most charming stories in the collection, “Long Walk to Forever,” is simply a beautifully written tale of Newt and Catharine, old friends who don’t realize they love each other until it’s almost too late. Newt is overly shy and “covered his shyness by speaking absently, as though what really concerned him were far away — as though he were a secret agent pausing briefly on a mission between beautiful, distant, and sinister points.” At a crucial moment, “Catharine burst into tears. She turned her back to Newt, looked into the infinite colonnade of the woods.”

Gone are the sardonicism, the ideology, and the global visions, but Vonnegut’s little sketch is a masterful study of human emotion, as is “Next Door,” a Cheeveresque tale about overly protective parents whose attempt to spare their child from a movie that “isn’t for children” ends up inadvertently exposing him to the homicidal rage of a jilted mistress.

How have these stories weathered the times? Are “Welcome to the Monkey House,” which first appeared in Playboy back in 1968, or “Harrison Bergeron,” a story about a society that crushes exceptional individuals, from 1961, timeless classics like Philip K. Dick’s “The Minority Report” or “The Man in the High Castle”? Certainly some of the territory is dated. The sexual revolution has long passed, and population control, another theme that’s prominent in the collection’s signature story, is a far less cut-and-dried issue, with China’s one-child-per-family policy and some countries, like the U.S., actually experiencing a decline in population growth.

Though “Unready to Wear” (1953) does offer the prospect of literal out-of-body experience, the satire of “More Stately Mansions” (1951), with its keynote line, “There’s more to life than decorating,” doesn’t really transcend its 1950s suburban setting. Indeed the satirizing of ’50s and ’60s suburban and exurban mores (Vonnegut was a resident of Barnstable, Mass., and later Sagaponack) also dates many of these tales.

And what’s “New Dictionary,” a catty review of the Random House dictionary dating from 1967, replete with a snipe at Bennett Cerf, doing in the collection, other than to provide unnecessary padding?

The denouement of “The Foster Portfolio,” published in 1951, is an almost textbook example of “compromise formation,” a precept that undoubtedly had great cachet during the heyday of American psychoanalysis, when the story was written. “He had the respectability his mother had hammered into him,” Vonnegut’s narrator reports. “But just as priceless as that was an income not quite big enough to go around. It left him no alternative but — in the holy names of wife, child, and home — to play piano in a dive, and breathe smoke, and drink gin, to be Firehouse Harris, his father’s son, three nights out of seven.”

However dated some of the themes, it is in the flashes of truly elegant writing like this that the genius and longevity of many of these pieces ultimately lie.

Mr. Sumner’s essay “Building the Monkey House,” which accompanies the volume, exhumes unpublished drafts that are then compared invidiously to the published text. One can understand the attempt to fathom the author’s process. However, it’s almost as if Mr. Sumner were capping off this “Special Edition” with a disclaimer when he says “to my mind the published version has always felt more mechanical, its vulgarities more forced, than what we find in Vonnegut’s best work.”

It’s hard to see how these disappointing fragments — several, for example, sport the turgid title of “Desire Under a Hot Tin Streetcar” — support this view.

Francis Levy is a Wainscott resident and the author of the novels “Erotomania: A Romance” and “Seven Days in Rio.” He blogs at TheScreamingPope.com and on The Huffington Post. His reviews, “Guestwords,” and stories have previously appeared in The Star.

Gregory D. Sumner is the author of “Unstuck in Time: A Journey Through Kurt Vonnegut's Life and Novels.” Vonnegut died in 2007.