Long Island Books: Bearing Witness

“In Paradise”

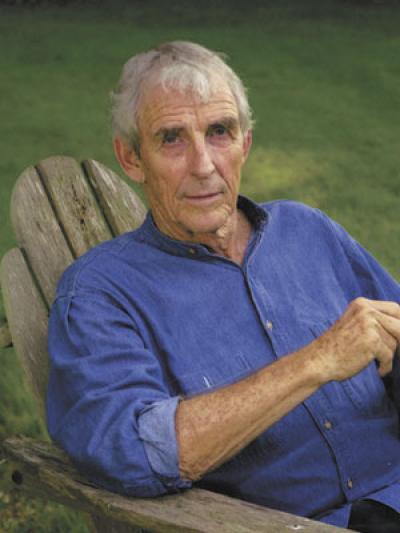

Peter Matthiessen

Riverhead Books, $27.95

Can one win multiple National Book Awards and still be an underappreciated writer? This may be the case for Peter Matthiessen, who won awards for “The Snow Leopard” and “Shadow Country.” When critics discuss what has been referred to as the greatest literary generation of the United States, those writers who began to emerge in the post-World War II years — Philip Roth, John Updike, Don DeLillo, Norman Mailer, Saul Bellow among them — Matthiessen’s name is rarely, if ever, included. Although certainly a recognized and admired writer, the appreciation of Matthiessen’s fiction seems relatively modest compared to that of many of his contemporaries given the scope and quality of work he has produced.

One may argue that this comparative neglect is because of the divided nature of his work as both a fiction writer and nonfiction writer and the fact that his best-known work is in the latter category. Or it may be that Matthiessen simply went about much of his life, traveling and writing, focused on the causes that moved him intellectually, morally, and spiritually without a great deal of self-promotion for his fiction. For many years, he maintained the charming notion that the work he produced should stand on its own without his having to provide interviews or go on book tours to sell it.

The overwhelming number of his more than 30 published works are nonfiction, and those works brought him his greatest public, if not critical, attention. Many of these books were written precisely with the idea of bringing public attention to issues and causes Matthiessen strongly believed in. In some cases, the work was polemical, as in the cause of Leonard Peltier and the American Indian Movement presented in “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse” or the unionization of farm workers in “Sal Si Puedes: Cesar Chavez and the New American Revolution.”

Other books emerged from his own personal involvement in particular issues and ideas, both local and transcendent, such as the plight of Long Island commercial fishermen in “Men’s Lives” or Zen Buddhism in “Nine-Headed Dragon River.” Still other nonfiction works resulted from Matthiessen’s environmental advocacy and worldwide traveling, as seen in such works as the seminal “Wildlife in America,” “The Tree Where Man Was Born,” “The Cloud Forest,” or “Tigers in the Snow.”

The works of fiction came far less often than the nonfiction works, and never lingered for too long on the best-seller lists, if at all. Nevertheless, fiction writing remained Matthiessen’s first love, and he resolutely proclaimed himself first and foremost a fiction writer who happened to also write nonfiction. But following his first three novels — “Race Rock,” “Partisans,” and “Raditzer” (published between 1954 and 1961) — Matthiessen published only six more novels over the next 53 years. His books of nonfiction for the same period are more than double that number — causing him to comment in his brief preface to his short-story collection, “On the River Styx,” that he wrote “a bit too much nonfiction.”

Each of those six novels, beginning with “At Play in the Fields of the Lord” in 1965, though, is outstanding, and at least three are singular and lasting achievements: “Far Tortuga,” “Killing Mr. Watson,” and “Shadow Country.” Fittingly, his final published work, appearing just days after his death from leukemia, is a novel, “In Paradise.”

The novel takes place in 1996 at a weeklong retreat for 140 pilgrims at the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp in Poland. The participants represent a wide variety of nationalities, ages, and faiths. Their purpose over the course of the week is to commit themselves to “homage, prayer, and silent mediation in memory of this camp’s million and more victims” in order to bear witness to “man’s depthless capacity for evil.” (The inspiration for the novel was Matthiessen’s own participation in three meditation retreats at Auschwitz. Although he wanted to write about his experiences there, he did not feel qualified to write a nonfiction work about the camp and the Holocaust “as a non-Jewish American journalist.” Fiction, however, allowed him to examine “the great strangeness of what I had felt.”)

Matthiessen develops only a few of the participants as fully realized characters. Most serve more as stock characters or representatives of particular ideas and reactions concerning the Holocaust. Each evening the retreatants come together to discuss their day’s experiences and to express their individual and collective reactions. At times cruel, accusatory, and contemptuous, these evening discussions spare no individual or group. The Germans, Poles, Catholics, Christians, and even the Jews are at various times blamed for causing the Holocaust, perpetuating it, rationalizing it, or forgetting it.

One character in particular, Earwig, is the designated antagonist. He finds fault with almost anything anyone has to say. All are complicit, in his view, and he is openly disdainful of the other participants’ struggles to express their feelings and ideas.

As one might expect, this novel is more concerned with ideas than character development. Part history, part distillation of the memoirs of Primo Levi, Aharon Appelfeld, Tadeusz Borowski, and others — Matthiessen has constructed a meditation on the “incipient evil in human nature” and our capacity for forgiveness. He poses large, important questions: Whose cruelty, suffering, and guilt are the worst? What does one do to survive and what is the cost to themselves and to others in doing so? Are we able to forgive or be forgiven? Is redemption possible? Is transcendence?

Of course, these questions are, for the most part, unanswerable — or have as many answers as there are individuals at the retreat. In fact, Matthiessen raises the basic question of why even come to such a retreat. What can possibly be accomplished there? The participants are all on “painful missions incompletely understood, by themselves perhaps least of all.”

The central figure among the group is D. Clements Olin, a Polish-born American poet and a professor of 20th-century Slavic literature at a Massachusetts university. He has a special interest in the survivor texts, and is at the retreat ostensibly to do research for a book on Borowski, the Polish writer and concentration camp survivor. However, Olin is also searching for information about his unwed mother, whom he never knew. Abandoned by his father at the start of the war, she may have been killed along with her family at the camp.

Through the course of the week, Olin struggles not only with his experiences at the retreat but with his own identity and sense of belonging. A skeptic and non-joiner (he is not even an official participant at the retreat), he is a lonely and solitary figure without any meaningful and lasting relationships. He “hungers for clarification” of who he is and where and how he belongs.

During the week, a burgeoning relationship develops between Olin and Sister Catherine, a young, rebellious novitiate. While some readers may find the attraction between the two a curious plot development given the novel’s setting, it is indicative of Olin’s desperate need for some meaningful connection in his life. His search for belonging is to a certain extent each person’s search for human understanding and connection. And Olin’s tentative movement from outsider to personally invested participant is interwoven with the experiences of the retreat.

Matthiessen was always an ambitious writer who often experimented with narrative structure. The narrative of “In Paradise” is more fragmented than is usually seen in his work. He provides small vignettes or parts of the story, allowing them to linger with the reader and coalesce into the larger whole as the reader pulls back from the novel and lets the parts settle in the mind, much as the points of color merge into a picture as one steps back from a painting by Seurat.

In many ways, “In Paradise” is a typical Matthiessen novel — intelligent, graceful, precise, and contemplative. He maintains an authorial distance in telling the story, demonstrating a good deal of restraint and control, demanding the reader’s engagement in the story. He does not intrude or intercede on behalf of one position or another. With subtlety and thoughtfulness, each character is allowed his or her say. Like the retreatants, the reader too must meditate and decide.

“In Paradise” is not the equal of the very best of Matthiessen’s fiction, but it easily deserves a place among his novels. It is a testament that, even in his last years, he was capable of producing provocative and moving work filled with moral anguish and human sympathy. Within the American canon, few writers’ works taken as a whole are so beautifully crafted and written. To the last, he remains one of our most elegant and humane writers. His fiction needs no more honors; it simply needs more readers.

After teaching literature for 30 years at Southampton College, William Roberson now teaches at L.I.U. Post. He is the author of “Peter Matthiessen: An Annotated Bibliography,” published by McFarland.

Peter Matthiessen lived in Sagaponack. He died on April 5 at the age of 86.