Long Island Books: The Believer

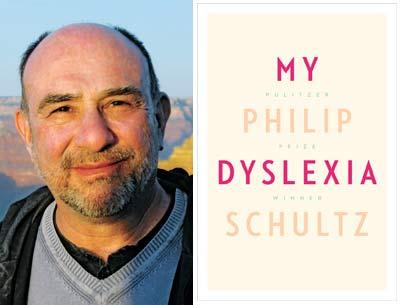

“My Dyslexia”

Philip Schultz

W.W. Norton, $21.95

I have read one scene in “My Dyslexia” over and over. Each time I read it, the writing is clearer, and the pain I feel when reading the words is more palpable: “I remember the first time I even considered the idea of being a writer. I was in the fifth grade when my reading tutor . . . asked me out of the blue what I thought I might like to do with my life. Without a moment’s hesitation, I answered that I wanted to be a writer.”

This answer provoked uncontrolled laughter on the part of the tutor, a former school superintendent, who thought it was hilarious that an 11-year-old boy who could not read wanted to be a writer. Although we feel the boy’s pain at the presumed humiliation when he was laughed at, Philip Schultz claims he was not offended or hurt by his teacher’s laughter because he himself totally understood the irony. Writing and reading are woven into one pattern. If you can’t read you can’t be a writer.

I keep imagining that the same teacher is still laughing at the same irony. His student has totally lived out the incongruity between what might be expected and what really happened. The boy who could not read has won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

For many years, Mr. Schultz did not have a label for his problems. He knew he was different from most of the other children in his class, and he fought his mockers and was disciplined, even expelled from school. He describes in spare detail how he was bullied and ridiculed because he was in the “dummy” part of the class, but “I didn’t discover I had dyslexia until I was fifty-eight years old, when my oldest son was diagnosed with it in the second grade. I learned from his neuropsychologist’s report that we shared many of the same symptoms, like delayed processing problems, terrible handwriting, misnaming items, low frustration tolerance for reading and most homework assignments involving writing, to name a few.”

The accumulated knowledge about dyslexia, including the diagnostic tools developed in the past few decades, has come about to the benefit of Mr. Schultz’s son and many others, but the author, with little help in the days when he was a boy, had to understand the tricks his mind played on his own.

“Every decision or idea attracts a horde of fierce self-commentaries which automatically refer to a vast switchboard of do’s and don’ts.” Even now, after all these years and experiences, Mr. Schultz admits he still has difficulty sitting down to read unless he tricks his mind with some distraction like online solitaire before beginning. “And when I make the mistake of becoming aware that I am reading, and behaving in a way that enables this mysterious, electrically charged process to take place, my mind balks and goes blank and I become anxious and stop.”

Developing a sense of self-worth is an important struggle for a child with dyslexia because dyslexics may be subjected to mockery and ridicule. The need for self-worth is not limited to children with dyslexia, however. Achieving a sense of it may be the central struggle for almost everyone. But individuals with dyslexia face additional hurdles. It is difficult to separate the idea that “there is something different about the way my brain processes information” from the idea that “there is something wrong with me.”

Despite this, the author observed, “Even when the entire world seemed to be ganging up on me, some persisting sense of myself argued on my behalf.” The ability to receive and process the arguments about self-worth being made on behalf of a person with dyslexia must vary greatly from individual to individual.

As I worked on this review, I became aware of why I was so interested in the passage about the reading tutor who laughed when the young Philip Schultz said he wanted to be a writer. Through my childhood and teen years, I had a speech impediment. I stuttered. Not all the time, but sometimes when faced with important moments.

After the point I had publicly declared my intention to enter the ministry, a profession that required a great deal of public speaking, there was an assignment to make a presentation in English lit class, but when I stood in front of my classmates to deliver my prepared words, I could not get the first sound out of my mouth. No matter how I tried to form the first word, it would not release. I shuffled, turned in a circle hoping I could unwind what had struck me dumb, opened my mouth, closed it. Then tried again, formed the sound with my lips, but that first word, all words, in fact, were locked up safely and would not escape on that occasion.

My classmates were laughing hysterically. It did not help when the teacher tried to explain, to cover for me: “Don’t you know what he was doing? He was miming.” I’m sure other people have had humiliating experiences that attacked their own sense of self-worth. My experience was an isolated incident, not a daily, lifelong struggle such as faces the person who lives with dyslexia throughout his childhood and youth.

Many of us know the flavor of taunting, ridicule, and bullying. “My Dyslexia” provides a sweet taste of success in how to overcome it. No matter how difficult it is to maintain the internal dialogue about self-worth, the effort is worth it. We are in the debt of Mr. Schultz, who has shared his experiences and thereby encouraged us all to persist and believe in ourselves. We should try for what we want most and try with all our hearts.

—

Philip Schultz’s collections of poems include “Failure” and “The God of Loneliness.” He lives in East Hampton.

Gary Reiswig is the author or “The Thousand Mile Stare: One Family’s Journey Through the Struggle and Science of Alzheimer’s.” He lives in Springs.