Long Island Books: Beneath the Swagger

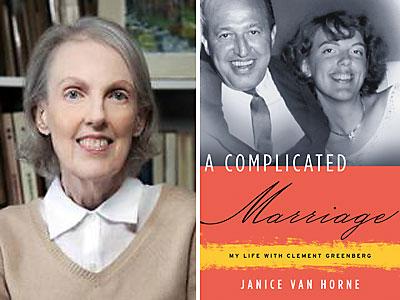

“A Complicated

Marriage”

Janice Van Horne

Counterpoint, $26

Clement Greenberg was one of the most significant — some would also say the most acerbic, bombastic, and pugilistic — art critics of the 20th century. He presided over the development of modernist art for some 40 years, championing American abstraction (he coined the term “Abstract Expressionism”), artistic taste and purity, formalism, and flatness in painting. He helped turn New York City into the capital of the art world, and he fueled America’s dominance in a global market.

Throughout, he extolled the art of then-emerging artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Hans Hofmann, and Robert Motherwell. And yet, in the last 20 years of his life Greenberg published little. He lectured mostly outside New York. By the 1970s, after Pop Art and Minimalism rose to dominance, his star had waned. Rebuked by cultural insiders who rejected his polemics, five years before his death in 1994 Greenberg was called “the most hated man in the New York art world” by the art historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Elizabeth Frank. He may have also been the most misunderstood intellectual in the untidy world of art criticism.

Perhaps he towered too high — became too cheeky, too immutable. Or maybe the art world simply regrouped. Greenberg was, without question, as arrogant and cocksure as he was brilliant. It is easy enough to find theoretical scholarship, biography, and ample gossip to expound on both the ascendance and the decline of this seminal figure in American art. But Janice (Jenny) Van Horne’s new memoir reveals a fresh perspective that sheds light on the interior life of Clement Greenberg, not only as the esteemed art critic but as a husband, lover, and off and on companion of nearly 40 years.

“A Complicated Marriage: My Life With Clement Greenberg” is an introspective journey through marriage and divorce, love and loss, celebrity and disillusionment. The book opens juicily enough to the night the couple met at a post-opening party in Greenwich Village. There, an impertinent Greenberg slapped his ex-girlfriend, the artist Helen Frankenthaler, after an imbroglio of some degree with her date. Nonetheless, Ms. Van Horne, a Bennington graduate — 21 years old to his 46 — managed to make sure the famed critic got her telephone number before the evening came to a close. They were married two months later.

Ms. Van Horne writes about her life with Clem in vivid, behind-the-scenes detail. In the beginning they lived in a world divided by 14th Street — the clubs and studios as well as their Bank Street apartment were all downtown; the pageantry was uptown. Ms. Van Horne, always the onlooker, never the looked-upon back then, recounts their early partnership with some amusement. They haunted dark clubs to see the likes of Lenny Bruce and frequented weeknight poetry readings featuring Kenneth Koch and Allen Ginsberg. At the club Bon Soir on Eighth Street, one of their favorites was an awkward 18-year-old with an unforgettable voice, Barbra Streisand. And many a night, of course, was spent at the Cedar Tavern, the famed art world watering hole.

While Ms. Van Horne’s prose sometimes drifts off into dreamy soliloquies, her attention to the details of personality and presence is inspired. An account of dinner at Lee Krasner’s uptown apartment, at which she suffered the misfortune of being seated across from Louise Nevelson, is priceless. Her bold characterization of the sculptor David Smith at his Bolton Landing studio is chilling, and memories of artists and artist couples such as Adolph Gottlieb, Annalee and Barnett Newman, and Pat and Clyfford Still are variously caustic, touching, or hilarious.

As she was an eyewitness to American art history, few of Ms. Van Horne’s memories are more revealing or possess more historic veracity than her recollection of the friendship she and Clement shared with Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. The couples spent innumerable weekends together, and although Jenny continued to feel like an outsider in Clem’s world, her accounts of history in the making are often incisive and canny.

In 1956, she persuaded Greenberg to take a summer share in East Hampton. Clem came out on weekends until August, when both he and Jenny were full-time summer residents. They’d spend the day at the beach and then move on to dinner at the Elm Tree Inn or to Jackson and Lee’s house in Springs. The two men shared a deep bond and in spite of the verbal combat that often erupted between them, they were confidants. The level of discourse seemed relative to Jackson’s sobriety — Ms. Van Horne speaks of him “white-knuckling his coffee mug” until cocktail time — but there was plenty of imbibing to go around. In fact, at times it seemed the entire infrastructure of the New York art world was on one never-ending bender.

Clement Greenberg’s promotion of Jackson Pollock is the stuff of legend, and it launched the artist into history as well as celebrity — maybe not the best contingency for a moody, self-critical alcoholic. Nonetheless, Pollock’s treatment of the canvas — replacing the subject in painting with painting itself — was the perfect muse for the ascent of Greenbergian theory.

Greenberg advocated nonobjective form in art, arguing that as the visual experience moved away from content it advanced to a higher form. He had a formidable intellect — his ideology was intractable — and his thesis would become one of the most significant contributions to the formation of a postwar American aesthetic. But after all the swagger, deep down Greenberg was a passionate lover of art.

Ms. Van Horne tells the story of the fateful weekend when Jackson Pollock and one of his companions, Edith Metzger, died in a brutal and highly avoidable car crash. With excruciating detail she outlines the events surrounding Pollock’s death. His failure to show at a summer concert prompted concern, and soon the call arrived — Jackson was dead, killed in a car crash on Springs-Fireplace Road. Ms. Van Horne’s recollections are crystal clear and, sad as it is, it is an irresistible read.

Throughout her tale, Ms. Van Horne struggles to find the truth in her own world. Life with Clem seems to have been a messy business inflamed by infidelity, restlessness, bouts of depression, and booze. There was tenderness, too, and a loving, if imperfect, affinity. She wrestled her way toward liberation and a life that included motherhood, acting, and the theater, maturing into a successful playwright. To her credit, she makes no attempt to explain Greenberg outside of their personal lives — in fact, she talks often of how inexplicable the art world appeared to her, leaving the analysis to the Ph.D.s.

Whether he was a megalomaniac, a genius, a frustrated painter and poet, or another guy avenging unsupportive parents, the story of Clement Greenberg is an intoxicating mixture of bravura, brilliance, and bombast. Janice Van Horne’s memoir sheds light on both the gospel and the man. Both intriguing subjects, to be sure.

Janet Goleas is an artist, curator, and writer living in East Hampton. Her art blog is at blinnk.blogspot.com.