Long Island Books: Beyond Local

In his new book depicting aspects of the history of the Town of Southampton, David Goddard, a sociologist, sets out to trace the “colonization of the village” in the late-19th century and to document “efforts at outside economic development.” These processes, he maintains, brought the town into the “modern age” and transformed it.

Geographically, the author concentrates on the Village of Southampton, Mecox Bay in Water Mill, and the Shinnecock Hills, that strip of “hills and valleys” east of Canoe Place and the Shinnecock Canal, between Peconic Bay to the north and Shinnecock Bay to the south. While the subtitle of “Colonizing Southampton” — “The Transformation of a Long Island Community, 1870-1900” — sets the scope in time, nearly a third of this study deals with periods prior to 1870 in an effort to establish the context for specific topics. Among them are two trials that pitted members of the “summer colony” and the town trustees against each other over issues that, the author points out, resonate today.

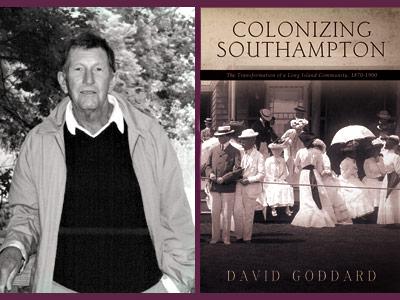

“Colonizing Southampton”

David Goddard

Excelsior Editions, $34.95

For background, Mr. Goddard tackles the complexity in the evolution of local government, beginning with the town trustees, a corporate entity. It is instructive to follow him. Legitimized by the colonial government of New York as an elective body by the Dongan Patent in 1686, the trustees held jurisdiction over the town’s common lands and its waters. In 1818, New York State legislation specifically required another, pre-existing group, the “proprietors,” to rely on the trustees to manage its material resources.

Numbering about 250 men by 1800, proprietors were either heirs of the first white settler-owners of the town’s land in the 1640s or subsequent buyers of rights in the undivided lands. Throughout the 19th century, some among this wealthy and powerful group took actions to reassert their authority, selling seasonal rights to cut grasses, collect seaweed, or harvest oysters, with the profits accruing to proprietor accounts, not the town coffers. In 1882, unbeknownst to the town trustees or to residents, the group took the bold step of selling the waters and the 1,200 acres of land beneath Mecox Bay to “outside capitalist interests.”

The private sale by the proprietors of the bay to the Mecox Bay Oyster Company galvanized opposition from the town trustees, and from baymen and farmers in particular, whose livelihoods, in part, depended on the bay. Intending to cultivate oysters from seed, the company’s president, Richard Esterbrook Jr., a lawyer, the son of the founder of the fountain pen company, and a summer resident of Bridgehampton, had married the daughter of Suffolk County Judge Abraham T. Rose, a member of a leading proprietor family. It is an example of the relationships profiled so well in this book. The marriage almost guaranteed Esterbrook knowledge of the proprietors’ intent to sell.

In 1885, the town trustees, under the group’s president, George White, a farmer and former whaling captain, took the company to court, charging that the proprietors had sold property that belonged to the public. They won the case and two subsequent appeals. The judge found that the proprietors held no ownership interest in the waters, the lands beneath them, or their products. In 1890, with no more land to sell, the proprietors disbanded, enabling the town trustees to gain “greater support and legitimacy” in exercising their responsibilities.

The second case occurred shortly thereafter. The emboldened town trustees took Frederick Betts, a corporate lawyer and resident of Southampton’s summer colony, to court. The long-simmering conflict at hand addressed the use of a small portion of beach owned by Betts between the ocean and Lake Agawam in Southampton Village. It was a place where locals launched fishing boats, mended nets, and cut up the occasional whale that drifted ashore. That is, it was a “work space” that year-round residents came to view as public land. To Betts and his city friends, however, it was a “restful zone of contemplation.” Betts had even threatened to fence it off.

In 1892, the case was heard at the State Supreme Court in session in Riverhead. Trustee George White’s testimony summarized the acrimony: “the city people . . . didn’t think it suitable to bathe with the country people.” The court, however, ruled against the town trustees and affirmed Betts’s ownership of the beach, but only as far toward the ocean as the mean high water mark. The court also recognized the beach as a “highway” that the public had the right to pass over. The decision survived appeals and was settled in 1897.

On these issues, namely ownership and use of bay bottoms and public rights of way on the beach, the final case decisions in 1885 and 1897 appear, in Mr. Goddard’s recounting, to be the understandings that govern the town today. Challenges have abounded. Readers of this newspaper will recall the photograph of a fence erected recently on Georgica Beach. One hundred and thirty years after the court decision, Betts’s threat became a reality in an adjacent town.

Besides the trials, Mr. Goddard describes the many efforts by investors, largely from New York City, to develop large-scale real estate projects in Shinnecock Hills during the period of 1880 to 1930. The groundwork was laid in 1859, when the proprietors bargained with the Indians to divide the area between the tribe and the proprietors. Subsequent private sales allowed the Long Island Rail Road to come through in 1870. Sales in the 1880s resulted in the building of a hotel, a depot, summer cottages, a golf course (in 1891), a yacht club, an Episcopal church, and other projects. By the end of the Roaring Twenties, however, the vision of transforming Shinnecock Hills with “hotels and villas” had failed — except for the golf clubs.

In this history, Mr. Goddard has reached beyond the local to produce an analytic study of business interests and conflict. He has deciphered the multiple strands of activity at play and provided judicious explanations of behavior. Yet his broad categories — “traditional community” on the one hand, and on the other the “summer colony,” “upper-class newcomers,” and “an entrenched upper-status group” (by 1930) — may not accurately describe the two entities or the tensions between them. In the author’s own narrative, conflicts engross smaller groupings or their subsets. In certain instances of economic strife, only some baymen participate, rather than whole groups such as Mr. Goddard’s “poorer social classes” or his “marginal class” of baymen, blacks, and Indians.

While “marked class and status divisions” surely characterized portions of society by the 1880s, I’m not convinced that a goodly portion of the year-round residents were conscious of occupying the lower rungs on the social ladder or of being colonized. Again, Mr. Goddard seems to me to dismiss the complexity in his narrative when he suggests that the “transformation” in the subtitle was from a community with a unique past to one that had become the “history of the summer colony.”

These reservations aside, this detailed book makes significant contributions to our historical understanding by tracing the development of governmental institutions, elaborating on the meanings of key colonial laws, placing legal cases in their social contexts, summarizing the history of Shinnecock Hills land transactions (as well as those of Montauk), and identifying the roles played by prominent figures among the Shinnecock Indians, provincial officials, the early English settlers, the proprietors, town trustees, administrative officers, and members of the summer colony.

Relying, in the main, on published government documents, newspapers, and secondary studies, Mr. Goddard has forged the often disparate pieces of Southampton history into an interpretive whole, and he has made sense out of the dramas in the town’s legal, business, and social history.

—

David Goddard, the author of “The Maidstone Links,” is a former professor of sociology at the City University of New York. He lives in Plattsburgh, N.Y.

Ann Sandford is the author of “Grandfather Lived Here: The Transformation of Bridgehampton, New York, 1870-1970.” She lives in Sagaponack.