Long Island Books: Buy Low, She Said

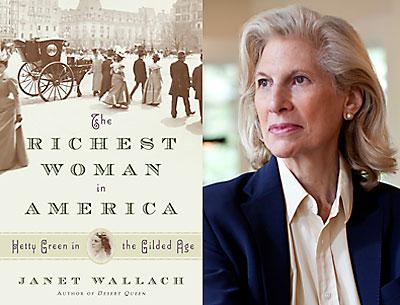

“The Richest Woman

in America”

Janet Wallach

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, $27.95

“If a man had lived as did Mrs. Hetty Green, devoting the greater part of his time and mind to the increasing of an inherited fortune,” reported a New York Times obituary in 1916, “. . . nobody would have seen him as very peculiar — as notably out of the common.” Had Hetty Green been a man, even today her name might be more often mentioned among the great financiers of the Gilded Age. In her time, as the biographer Janet Wallach notes, Hetty was acknowledged as “Queen of Wall Street,” New York City’s leading lender, a woman who would have ranked on the current Forbes 400 list with holdings that would be valued at an equivalent of $2 billion.

“I buy when things are low and nobody wants them,” was Hetty’s frequently iterated ideology. “I keep them until they go up and people are crazy to get them.” Brokers scrambled over one another to watch Hetty’s every move; her utterances were of as much interest to the press as those of Warren Buffett today.

What a delight it is to find Hetty Green! Ms. Wallach’s “The Richest Woman in America: Hetty Green in the Gilded Age,” published by Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, is one of a handful of biographies written on this subject. The research findings are slim, the author notes. There were no diaries, journals, or correspondence to pick over — only thousands of articles of varying reliability from newspapers and magazines from around the world.

As such, Ms. Wallach calls her work more of “an impressionistic painting” than a traditional biography. As she did with her best-selling “Desert Queen: The Extraordinary Life of Gertrude Bell,” the author nonetheless succeeds in bringing her subject vividly to life. Hetty comes off as a kind of shrewd, eccentric aunt who might dominate your holiday table. Through her, the excesses and hypocrisies of the Gilded Age come into sharp focus. “I am glad Miss Gladys Vanderbilt is not my daughter,” said Hetty, footnoting a trend toward marrying the daughters of great industrial fortunes to titled nobility. “Girls who go to Europe to get their husbands deserve what they get and more.”

Hetty Howland Robinson was born in 1834 in New Bedford, Mass., into a Quaker home. Her overbearing father, Edward Robinson, was no doubt drawn to Abby Howland’s whaling fortune. Nonetheless, he was sorely disappointed by his wife’s inability to bear a son. Hetty, their only child, was intermittently farmed out to her grandfather’s care; the women of the house — a step-grandmother and a maiden aunt — cared for Hetty haphazardly. In defense she developed fiery temper tantrums. As her father’s eyesight dimmed, Hetty found salvation. She filled the breach by reading stock market reports aloud to her father and accompanied him on his business rounds. “There is nothing better than this sort of training,” she said. Money became the hearth of Hetty’s unhappy home.

Early on, Hetty developed an interest in the effect of compound interest on a dollar saved. Edward Robinson sent his daughter, a budding debutante, to New York with $1,200 to buy the clothes needed to find her way in high society there. She used $200 for gowns and invested the rest in bonds, which, she proudly reported to her father, had grown in value. Thus was born Hetty’s legendary reputation for frugality bordering on the miserly. It wasn’t what money could buy that mattered to her, but the accumulation of wealth itself, which she did chiefly through railroads stocks, mortgage bonds, and foreclosed real estate. While others flocked to make an overnight fortune, Hetty bided her time and did her homework. When the bubble burst, she took the spoils.

Even when she was in command of many millions, Hetty — a handsome woman, dressed perennially in Quaker black — often looked like a charity case. “This eccentric woman,” wrote The Boston Evening Transcript, “certainly proves that the possession of money and its use for personal adornment are not inseparable in the makeup of womankind.” While other Gilded Age financiers built Fifth Avenue palaces, Hetty lived in modest boarding houses all over the city and in Hoboken, N.J., frequently moving to avoid the taxes that came with a permanent residence. When the city assessed her for $1.5 million in back taxes, Hetty produced the documentation in court to prove them wrong. She thrilled to the din of litigation almost as much as the ka-ching of money piling up in her bank account. Hetty was endlessly suspicious of being taken for her money and feared being poisoned. She loved her pets because “they don’t care how rich I am.”

It would be so easy to reduce Hetty to a caricature; indeed, the press did at the time. But Ms. Wallach has created a woman in full. Hetty married Edward Henry Green, a financier, at the advanced age of 34 and had two adored children. They lived quite happily in London and New York on Edward’s fortune, as stipulated in her prenuptial agreement — though, as Ms. Wallach notes, business was still business. Hetty booted Edward when he used her funds as collateral against his sinking enterprise. Nevertheless, they remained tender friends until the end of his life.

Hetty doted on her son, Ned, and fretted over her retiring daughter, Sylvia, for whom she sought a husband whose ardor wasn’t colored by dollar signs. In the absence of concrete evidence of Hetty’s thoughts, Ms. Wallach draws from Dr. Sloper of Henry James’s 1880 short story “Washington Square”: “My daughter is a wealthy woman with a large fortune. She is about as intelligent as a bundle of shawls.” If Ms. Wallach uses smoke and mirrors on occasion to tell her story, she does so with flair, calling on period luminaries such as Edith Wharton and Mark Twain for an assist.

Disappointingly, Hetty was no feminist, engaging in a practice of personal exceptionalism. She herself preferred to “have a part of the great movements of the world . . . and to deal with big things and big men.” But for women in general, she allowed that “the chief sphere of woman is home; her most important duties are that of wife and mother.” She believed in business education for women to understand a man’s pressures, but she advised that the best way to be a good wife was to make yourself “pretty as a wax doll” for his homecoming at the end of the day. “I don’t believe in suffrage,” Hetty said, “and I haven’t any respect for women who dabble in such trash.”

Part of why “The Richest Woman in America” is such an entertaining read is that Ms. Wallach places the character of Hetty firmly in her time and against her social class, of which she was its antithesis in most ways. The crisp narrative moves smoothly between the New York drawing rooms and Newport cottages of the Astors and the Vanderbilts to the antics of Hetty, who thought nothing of entering into a shoving match with a disagreeable maid. Ms. Wallach notes a lavish dinner party at the Knickerbocker that featured a duck pond with live ducks, and another for the Duchess of Devonshire in which rosebushes ran down the center of the dining table. The fabulously wealthy played at living like royalty in displays that rivaled the court of Louis XIV.

Cut to Hetty, whose salty style of speech, hilariously, throws cold water on all pretense of nobility. “He wants me to stop talking, and I want him to stop snoring,” said Hetty of a judge in one of her numerous court cases. “He makes his noise with his nose, and I make mine with my mouth. It’s nearly the same, ain’t it?”

Hetty Howland Robinson Green was what we all aspire to be: unabashedly ourselves and a success in spite of it. That she was a businesswoman on an epic scale in the age of corsets and crinolines makes her nothing short of a phenomenon — inspiring a hundred years later, in our “liberated” time, when women still walk on eggshells in high-finance spheres. “She had enough courage to live as she chose . . . and she observed such of the world’s conventions as seemed to her right and useful,” wrote The New York Times at her death.

Ms. Wallach has accomplished a feat in her portrait of Hetty — a worthy biography that’s also a page-turner.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor of the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” a humorous how-to that culls the lessons of the great romantic women of history. She lives in Springs.

Janet Wallach lives in Amagansett.