Long Island Books: Cornpone No More

“The Passage of Power”

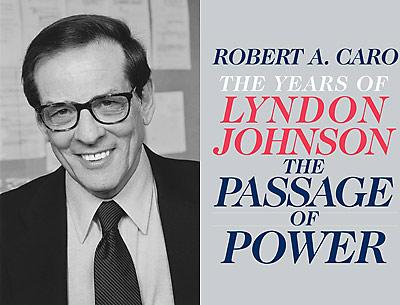

Robert A. Caro

Knopf, $35

Show me someone who thinks of history as the dry recitation of accumulated facts, and I’ll show you a person who has never known the pleasure of reading a book by Robert A. Caro.

The fourth volume of Mr. Caro’s leviathan biography of the 36th president of the United States, “The Years of Lyndon Johnson,” is a masterfully written account of a short but intense period of Johnson’s life. Titled “The Passage of Power,” it covers primarily four years (1960 to 1964) during which L.B.J., who had already turned himself into one of the most powerful and adept Senate majority leaders of modern times (if not of all time), campaigned for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination, lost the nomination to John F. Kennedy, agreed to run for vice president on the Kennedy ticket, served with increasing despair as vice president for three years, and rose, phoenix-like, from the relative powerlessness and obscurity of that job to take hold of the reins of government immediately after President Kennedy’s assassination.

At slightly more than 600 pages, this latest installment of Mr. Caro’s opus on L.B.J. is a compelling read. Its strength, I believe, is in the combination of a crisp, clear, journalistic writing style and comprehensive research into the people and events about which the author writes. One’s impression is that he left no memo or news account unread, no interview unconducted. He marshals, with sublime ease, an unimaginable array of facts. The payoff for the reader is a text that is engaging and memorable.

Perhaps the strongest theme in this book — as it is in much of Mr. Caro’s work — is the question of power, the passion for which was close to the core of L.B.J.’s animus. “Another continuing motif of Lyndon Johnson’s career — one that had been repeated in every institution in which he had climbed to power — was that the more power he acquired, the more he reveled in its use,” Mr. Caro writes, “flaunting it, using it often just for the sake of using it, bending men to his will just to show that he could. . . .”

Dating from his time at an obscure teachers college in South Texas, the Johnson pattern was to take for himself seemingly insignificant jobs in government and unobtrusively accrue to those positions greater and greater influence.

Because political power was the currency Johnson was most comfortable dealing in, many of the people close to him were surprised that he chose to accept Kennedy’s offer of the vice presidential nomination at the 1960 Democratic Party convention in Los Angeles. Up to that point in American history, the vice presidency had generally been something of a laughingstock, a largely ceremonial position characterized by boredom rather than power. Apparently, however, Johnson felt as though he had no choice but to accept the offer to become Kennedy’s running mate. He campaigned earnestly, struggling, as he often had to do, to get the public to see him as progressive and liberal, rather than as a Southern conservative. (Mr. Caro’s treatment of Johnson’s record on civil rights is nuanced and fair.)

After victory over the Republican ticket of Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge, President Kennedy and Vice President Johnson began an increasingly frustrating working relationship that was never satisfactorily resolved. “Lyndon Johnson,” we are told, “who had devoted all his life to the accumulation of power, possessed now no power at all, and as Vice President the only power he would ever possess was what the President might choose to give him. He understood that now: understood that it was imperative for him to remain in the President’s good graces. All his life Lyndon Johnson had been as obsequious to those he needed as he had been overbearing to those he didn’t — and now he needed Jack Kennedy desperately.”

To make matters worse, it became bitterly clear to the man whose roots were in a tiny, hardscrabble South Texas town that he and his wife were objects of derision among many members of the president’s inner circle, who formed a kind of “smart young set” of the era.

“Some of the New Frontiersmen had a gift for words, and the terms that finally became the accepted nicknames for Lyndon Johnson in their social gatherings — ‘Uncle Cornpone’ or ‘Rufus Cornpone’ — were, in their opinion, so funny. They had a nickname for Lady Bird, too, so when the New Frontiersmen referred to the Johnsons as a couple, it might be as ‘Uncle Cornpone and his Little Pork Chop.’ The journalists who, as members of the in group, were at the parties would hear a West Winger laughingly refer to ‘Lyndon? Lyndon Who?’ and references to the situation would creep into print.”

That “situation,” like so many other things, was to change forever on a Friday in Dallas in 1963. Mr. Caro’s description of the events of Nov. 22 and the several days following are particularly rich in detail. Knowing his subject’s character as well as he does, he speculates that L.B.J. had probably given at least some thought to what would happen if he had to assume the presidency suddenly. Sitting in the high-backed chair reserved for the commander in chief aboard Air Force One en route back to Washington with his predecessor’s body, now-President Lyndon Baines Johnson pulled a pad toward him and wrote three words: 1) Staff, 2) Cabinet, 3) Leadership.

“But if ‘leadership’ as he wrote it on the pad referred only to a meeting of congressional kingpins,” Mr. Caro tells us, “the word also had broader connotations, and he showed not only that he knew what to do — but that he had the will to do it.”

Of President Johnson’s meeting that very evening with Congressional leaders, Mr. Caro quotes Hugh Sidey, a journalist and longtime observer of the presidency. That session, Sidey wrote, contained “the real clue to [Johnson’s] flawless assumption of power. The evening had no real purpose. It was a kind of tribal ritual of those men who wielded power in the legislative halls [where] meetings are a way of life and a sign of authority.” Once Johnson had called such meetings, summoning such men. He hadn’t called one for three years. But now he had called one again. And, Sidey wrote, “those men understood.”

Of particular interest is Mr. Caro’s handling of the longstanding feud between Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy — “bad blood” more than a feud, really. He details how Bobby Kennedy tried to convince his brother to withdraw the offer of the vice presidency to the despised Lyndon Johnson and how, when his brother refused to do so, the future attorney general tried to convince Johnson not to accept it. Along with the matter of power, the toxic relationship between L.B.J. and R.F.K. is a recurring motif throughout this book.

One of Mr. Caro’s virtues as a biographer and historian is that he assiduously avoids judging the people and events he writes about, allowing the facts to speak for themselves. This is an implicit compliment to the reader, allowing him to make his own assessments. As one whose first exposure to the events Mr. Caro illuminates was as “current events,” I was struck by how very much times have changed. Whatever one makes of Lyndon Johnson and John and Robert Kennedy — arguably all of whom are the protagonists of this particular volume — it seems irrefutable that these were people of entirely different stature from those who are the political players and leaders of the present era.

Robert A. Caro has a house in East Hampton.

James I. Lader, a weekend resident of East Hampton, regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.