Long Island Books: Doppelgangers

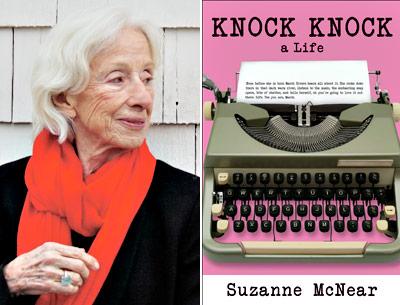

“Knock Knock”

Suzanne McNear

Permanent Press, $28

Feet in autobiography, heart in the novel, Suzanne McNear’s “Knock Knock” plays around with what’s what in the wide, seductive world of literary possibility.

Although it is the autobiographical story of a life, the book is marked by the absence of the first person. Ms. McNear has replaced the I of herself with a character, a protagonist by the name of March Rivers, who shares the details of life with Ms. McNear but performs them at a narrative distance. This choice defines the book, giving it a near-far stance that seems to mirror the embracing of life and the alienation from it practiced by March Rivers herself. Sometimes the reader has a sense of March-McNear; sometimes it is a sense of her slipping away.

The book is very much characterized by an edgy, quirky, syncopated style. The story told in “Knock Knock” is chronological, specific to time and place, detailed in execution. March Rivers is born in 1934; she is raised in an affluent family in the smallish Midwestern city of La Rue, Wisc.:

“Within this family March is briefly cushioned from the world in a pink bassinet with lace canopy, and a nursemaid to watch over her, but almost from the beginning she is perceived to be a problem.”

The problem appears to be fitting in, or, more broadly defined as the book moves forward, fitting in to herself and finding a way in the world. March goes to boarding school on the East Coast, then to college at Vassar, then begins a life in New York that stalls with the end of an ill-fated love affair, the kind of love affair a girl like that was not supposed to have in those times.

One thing leads to another with another beau, Warren, and a pregnancy leads to their marriage. There’s a move to Chicago. Three children follow. But something is not right, in Warren, or in the marriage, or in March, or in the combination:

“March was going to get to the bottom of this. Busy as she was, she was going to consider how to reshape Warren and herself and the children, and make something of them. Something normal, even admirable. First she would pinpoint how they had got off the track, then find out how to get back on. Had they ever been on? Maybe not, but change was always possible. She knew.”

The end of March’s marriage to Warren comes with a period of intense difficulty — a nervous breakdown, if that’s not putting too fine a point on it. She struggles to survive, psychologically and emotionally, and struggles to maintain a livable environment for her three children.

There were, strangely, some good days; when she was fooled into thinking she had come through, times when she looked at the world and felt like she was falling in love with it, with all the people out there, all the men and women and children who had the courage to get up, go out, fry an egg, stay out of jail, get out of jail, survive. What courage, what talent, what guts.

She thought at those times that she might indeed be looking for a job. She might be working on her novel again. Why not. It was a good novel. An important novel. To her. Why not to others.

March does pull herself together — she attends graduate school at the University of Wisconsin, then eventually begins an editorial job at Playboy magazine in Chicago. Some of the storytelling here can get choppy, with transitions perhaps suffering from cut-and-paste. Over the course of the book March is offered opportunities — a book contract (not pursued by March) for her novel in progress from an editor in New York, a job as a teaching assistant, the eventual job in the fiction department at Playboy magazine.

So the reader gets the message that March Rivers holds charm for others, and the reader is at times charmed by the clarity and honesty of the observations attributed to March on the topic of herself:

“She felt she might always be sad, that this sadness might not leave her, was that perhaps a choice? Was that correct? That conclusion? Sadness was the path she had chosen, and the best she might be able to manage was a life that was not too sad most of the time.”

Yet sometimes an understanding of and sympathy for March can lack continuity. The near-far quality of the March Rivers persona may be the culprit here. Ms. McNear sometimes strains in her efforts to capture herself in a double container.

Given that double container, is “Knock Knock” more of an autobiography or more of a novel? Maybe memoir is the best category for this one, with its elegant pronunciation and more ambiguous, literary connotation. The Oxford American Desk Dictionary and Thesaurus — that’s the thick, stubby one perfect for a quick look-up — points out that memoir is “written from personal knowledge or special sources.” Autobiography is just a plain old “written account of one’s own life.” So the difference seems to depend on an elusive aspect of the horse’s mouth.

For memoir, perhaps the writer must delve into that personal knowledge or those special sources, while for autobiography the writer can just lay down the facts, never mind so much from where, or from what depth, they come. Memoir then for Ms. McNear’s “Knock Knock,” definitely memoir. Because there is a special source, a document referred to in the work itself with some frequency: March Rivers’s novel.

As a whole, “Knock Knock” is about the writing of a book — over the long term, over the course of a life. March Rivers, it turns out by the end, is the character in the novel that March Rivers writes, has been writing since the end of her marriage, and glimmers of it perhaps even before. It begins at her very beginnings and goes right on through. This book is the who of March, and the what, and the how of self-definition. It is made explicit that “Knock Knock” had a former life as an unfinished novel, then a long, undisturbed life as pages in a box.

In the end, the book contains the unfinished, finishes it, and serves ultimately to render the circle of Ms. McNear’s life — thus far! — as told with March Rivers as a stand-in, an alter ego, a kind of literary scout probing the territory of identity.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton.

Suzanne McNear, a former theater reviewer for The Star, lives in Sag Harbor.