Long Island Books: Four-Legged and Wordless

Who’da thunk Franz Kafka would have said, “All knowledge, the totality of all questions and all answers, is contained in the dog.” Maybe his translator spelled dog backward by mistake. On second thought, perhaps it’s a fitting observation from the creator of several of literature’s most tortured souls.

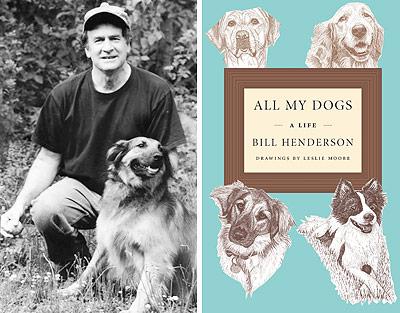

Bill Henderson, founder of the Pushcart Press, contemplates the dog-God connection in his just-published memoir, “All My Dogs: A Life” — this and much more.

Lulu, Max, Opie, Charlie, Airport, Sophie, Rocky, Ellen, the Mayor of Bridgehampton, Snopes, Earl, Duke, and Trixie, the dogs of Mr. Henderson’s life — not counting his current companions, Franny and Sedgwick — are guide dogs that have allowed the author to traverse the bumpy human coil while maintaining a communion with the beauty, innocence, and sense of adventure he knew as a boy in Penn Wynne, Pa.

“I never could live without dogs, at least not well. In my dogless years I was busy and ambitious but half alive . . . it’s about steady, honest, and unconditional love — which is the virtue of many faiths, both secular and traditional — which is why I stay close to my dogs and my faith.”

Fear not. “All My Dogs” ain’t sappy. Those who have read Mr. Henderson before — “His Son,” “Her Father,” “Tower,” and “Simple Gifts” — know his Twainish humor and clarity of voice. There are scenes in this 145-page gem that bring Jean Shepherd’s “A Christmas Story” to mind, Huck Finn, too, an American boy reluctantly coming of age.

In the introduction, Mr. Henderson notes that his is not the first dog memoir. He draws inspiration from a few other writers, Mark Doty, author of “Dog Days,” a favorite. It was Mr. Doty who wrote, “Love for a wordless creature, once it takes hold, is an enchantment, and the enchanted speak, famously, in private mutterings, cryptic riddles, or gibberish. . . . How on earth can I stand at the requisite distance to say anything that might matter?”

Mr. Henderson finds the requisite distance and uses it to take us through his life from the boy in Penn Wynne with his observant Presbyterian dad, collection of snakes, frogs, and other creatures from the nearby woods, school, the McCarthy hearings, a patient mother, a famous blue couch, and first dog, Trixie.

Duke was the second with whom the author explored the marshland of Ocean City, N.J., where “wilderness still had a few years to go.” The marsh was protected by the Henderson Game Commission with Duke the enforcer, and it was where Duke and his master came upon a dead dog — death for the first time. Sex reared its mysterious head about this time, and philosophy, and Duke’s archenemy, Dagger, from across the street.

Mr. Henderson writes about his dogless years, which began in 1959 when he left Duke behind to attend Hamilton College, Harvard grad school (a short stay), a Parisian garret, an ex-nun first wife, his disgust with dog-dismissing philosophers, a crib on Bleecker Street, the start of the Pushcart Press, and a “slouching hound” named Snopes he inherited when his mother passed away but not before he promised her a baby.

The chapter titled “The Ballad of Ellen & Rocky” is one of several sections of the book in which the innocence of wordless creatures cuts through the confusion and trials of human experience and shines a forgiving light (a holy light?) upon them. Mr. Henderson doesn’t hit you over the head with this. The events, which I will not divulge here except to say they involve a move to East Hampton, a woman, a breakup, a canine tragedy, and a humbling, speak for themselves.

“All My Dogs”

Bill Henderson

David R. Godine, $19.95

Then comes a dancing yellow Lab and an unexpected child. “Love is a word that only children and dogs say truly. For the rest of us, love is corrupted every day by a cynical culture and our own never-ending qualifications.” Sophie dies and the sadness is replaced by Opie, a beagle with papers, the son of Bruno, the Duke of Eqununk, and Lady Sand Pebbles III, a handful. Pushcart grows, as does a wooden tower the author constructs on a hilltop in Maine.

The book contains wonderful passages like Mr. Henderson’s description of how “Pushcart Press occupied the space under my bachelor’s double bed. The bed filled most of the apartment and was supported by boxes of books. In good weeks, the bed sank closer to the floor as orders left . . . in bad weeks, when unsold books were returned, the bed rose again, sometimes at an awkward angle.”

And when his daughter asked:

“How do crickets sing, Dad?”

“Well, they rub their legs together —”

“But how does that make music?”

Long ago I had wondered about that too. But time had passed, and I forgot to wonder, just as time rushed over the people buried in this cemetery and over the three of us sitting on this hillside watching for brief, sudden passages of light.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“The Hymn of Lulu & Max” is the last chapter. Mr. Henderson tells of becoming reunited with the boy Bill Henderson in the Maine woods alongside Lulu. I will save the almost supernatural but troubling coincidence that takes place as well as the much-needed revelatory “force” felt not long after the author’s last hike in Maine with Lulu “into a gold October valley, over maroon blueberry fields to the Frost Pond. Lulu swam, and I just lay on the field and watched the clear sun-washed sky and wondered if anything would ever be this perfect again.”

A book agent friend of mine told me recently that a novel had to be at least 300 pages long. I thought this would disappoint the author of “The Old Man and the Sea” and other shorter novels, and it got me thinking about the book biz in general.

The agent was obviously speaking about what publishers wanted to see in a novel, that being pages enough to be marketed as one. Has it really come to that? I had a professor who once warned us against wordiness. He joked that he might start grading our papers according to their weight. He’d throw them out the window and the first one to hit the ground would receive an F.

Bill Henderson’s short memoir gets an A, a brilliant book with a deep, grateful bow to the wordless creatures among us.

—

Bill Henderson lives in Springs.