Long Island Books: Fresh Meat

Every “Seinfeld” fan recalls the episode in which Jerry’s wacky neighbor incorporates himself and takes on a young intern named Darren. Darren’s duties at Kramerica include laundry detail and scheduling high tea with a certain Mr. Newman. We laugh because it’s clever. It doesn’t matter that the kid’s being used, that he’s wasting money on empty credits and ridiculous experiences. Sanity prevails in a neat 22 minutes when his college dean puts a stop to it.

But what if no one comes to Darren’s aid? What if he’s not really a bit player on a sitcom but a symbol of something real that’s taking place globally right now? The joke is no longer funny, and the laugh track that follows each one of Cosmo’s draconian demands becomes grotesque and more than a bit shameful, which is precisely why Ross Perlin includes dialogue from this episode in a chapter of “Intern Nation: How to Earn Nothing and Learn Little in the Brave New Economy.”

Mr. Perlin, a native of New York City and graduate of Stanford, explores the essence of what it means to be an intern in this impressive muckraking exposé. Who are these people and what exactly do they do? Interns might fetch coffee or do cartwheels in a Mickey Mouse costume. Some write speeches for senators, while others make copies like nobody’s business. Sometimes they’re paid a minimum wage, sometimes not. They’re the privileged children of country club buddies from New Haven, but also that scholarship kid who crashes on friends’ couches while he works for free.

Interns could be just about anybody and do just about anything, which is why their waters are often so muddied. “The very significance of the word ‘intern’ lies in its ambiguity,” Mr. Perlin explains.

The author begins his quest by describing a recent visit to Disney World: “The curtain rises . . . interns are everywhere. . . . Even Mickey, Donald, Pluto and the gang — they may well be interns. . . .” Disney has playfully confounded us with its brand of hocus-pocus for generations, yet that’s nothing compared to the way it has completely reimagined the role of the college intern.

In exchange for the prestige of the Disney name on a résumé, interns “earn their ears” by working completely at the company’s will. “Disney has figured out how to rebrand ordinary jobs in the internship mold,” Mr. Perlin writes, “framing them as part of a structured program . . . without sick days or time off, without grievance procedures, without guarantees of workers’ compensation or protection against harassment or unfair treatment.”

Despite these harsh working conditions, between 7,000 and 8,000 college students arrive each year at Disney to do the Mouse’s bidding. “We’re there to create magic,” one intern told the Associated Press.

As Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks continue to flock to Disney World, the same can be said of Chinese nationals. Once Disney’s H.R. team realized the big savings it was enjoying by having a perpetual work force of temporary employees, they decided to go a step further. Based on the federal J-1 Exchange Visitor Program, Disney’s international internship program was born. “Workers brought in from hundreds or thousands of miles away are always easier to control, even more so if the legality of their presence depends entirely on the employer.”

At least Disney goes through the machinations of a genuine internship for college credit. At the University of Dreams, a 10-year-old company in Redwood City, Calif., there are no real students taking notes simply because there are no professors handing out assignments or grades. “That’s right, you pay ‘U of D’ $1,000 per week to work, which makes college tuition look cheap.” Mr. Perlin reveals how the company makes no effort to ensure its clients a paid internship, which brings up the question of who should actually be paid for their work.

Unless an internship offers a substantial training program, and many do not, an intern is considered an employee entitled to minimum wage and other protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act. The author wonders why no one’s blowing any whistles, and the answer is quite sobering. The employer-intern relationship hinges on power: contacts, references, and impressive-looking résumés. Should interns start shaking up the workplace, demanding fair pay and treatment, it would completely defeat their purpose. How will they ever make it onto the A team if they don’t prove themselves to be team players?

The economic impact of all this free labor by willing victims is jaw-dropping. “Using up-to-date, but still conservative figures (500,000 unpaid interns at the 2010 federal minimum wage), the money that organizations save through internships approaches $2 billion annually.”

A recent national survey revealed that one out of 18 college freshman expects to become an actor, musician, or artist. “This is where ‘the rock-star jobs’ and the glamour internships are — the more glamour is perceived, the more vital the connections are and the less likely it is that pay will ever enter the equation.”

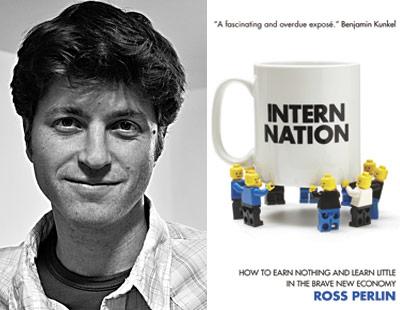

“Intern Nation”

Ross Perlin

Verso, $22.95

The dreams and desires of young people are as strong as ever, but without financial backing of some kind, how long can they actually pursue these interests? “Perhaps more than ever before, the rich are working and dominating particular industries.” Mr. Perlin interviews a young art history major, “John,” about his interning experience at an auction house to illustrate the point: “. . . one of the interns I was working with was literally royalty. The amount of work she was ready to do was next to nothing. Her father is a customer.”

This disturbing trend continues in Washington, D.C., where “job creation is preached, not practiced.” One Capitol Hill intern informs Mr. Perlin that out of every 30 interns, 25 of them may be “packed,” an insider term for the children of donors, friends, and important constituents. Interns aren’t paid on the Hill or at the White House, where even President Obama characterizes the experience as “answering the call to service.”

Despite the scandals between politicos and interns that have rocked the nation, the author maintains that this shameful practice is very much alive and well. According to the veteran political analyst Andrew Sullivan, some Washingtonians simply refer to their interns as “the flesh.”

Mr. Perlin’s timely book raises many questions about the future of our country. Critics might describe it as one-sided or accuse the author of ax-grinding if it weren’t for the fact that the book is so well written and thoroughly researched. Its message leaves us slightly stunned and more than a bit illuminated. Are interns taking their future into their hands, paying their dues until they’ve earned their way into a chosen field, or are they privileged children being handed something for nothing?

The answer is both. Yet what does it say about a country whose art, music, film, and politics are fueled almost entirely by the wealthy? Why do the powerful prefer to exploit our young for little to no pay and give handouts to friends of friends rather than mentor our best and brightest?

Mr. Perlin offers solutions, yet even these hinge on powerful entities finally doing what’s right. Colleges and universities must look out for their charges, keeping a safe distance from the “Wild West of sketchy internships,” and the Department of Labor must enforce the law. The world at large needs to understand that an intern is actually a type of worker and not a student.

Otherwise, Mr. Perlin suggests, it might be time to act. “A general strike of all interns would show all that they contribute for the first time. Bringing a delicious, low-level chaos to the world’s work. . . .” A low-level chaos, as I complete this review during the month of October in New York City — why does that phrase sound so eerily familiar?

—

Ross Perlin is a regular visitor to East Hampton, where he has family.

J. Bryan McGeever, a graduate of Stony Brook Southampton’s M.F.A. program, teaches writing and literature in the New York City public schools. His work has appeared in Thomas Beller’s “Lost and Found: Stories From New York.”