Long Island Books: The Great Divide

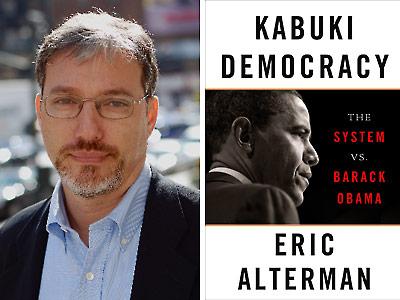

Eric Alterman’s latest book, “Kabuki Democracy: The System vs. Barack Obama,” analyzes the reasons why President Obama has failed to enact the progressive reforms articulated in his presidential campaign. In sum, Mr. Alterman depicts a system controlled by money and shadow play rather than participatory processes. He marshals an astounding amount of evidence from a wide range of sources to document his central argument: that the banking system, conservative institutions, the media, and lobbyists have warped democracy in the United States.

__

“Kabuki Democracy”

Eric Alterman

Nation Books, $14.99

__

His argument about the current political scene, then, becomes an argument about politics more broadly conceived — an argument about the failure of participatory democracy.

Yet, all of this left me, as a reader and a concerned citizen, as a parent and a teacher, strangely unmoved. I applaud Mr. Alterman’s appeals to logic. I applaud his use of substantive research to document his claims. I applaud his initial efforts to find common ground with a segment of the audience who would likely be dubious of his argument — those progressives who blame President Obama for failing to fulfill his campaign promises.

I also applaud his precise use of Antonio Gramsci’s theory about the function of ideology. In fact, the most complex and promising element of the book is his neat explication and application of theory to lay bare the techniques by which ideology, in this case the ideology of conservative politics, functions to convince people to act in ways that are at odds with their own best interests. The book is worth reading for this alone.

But Mr. Alterman perpetuates a problematic divide between progressives and conservatives. The dire state of politics in this country today requires conservatives and progressives to work together. An “us” and “them” or “red state” versus “blue state” approach loses viability when the stakes are the very credibility of the United States, as evinced in the recent crisis over the debt ceiling.

Not only does this dichotomy amount to a phantom conjured for the sake of publicity by the same new media that Mr. Alterman takes to task, it also conceals the simple fact that all of the states of the United States suffer when our credit rating drops. Similarly, divisive rhetoric only exacerbates the challenges of forging solutions to ocean acidification, rising sea levels, and other environmental problems, problems that require all of us to work together.

One might question whether Mr. Alterman, who is an English and journalism professor, has the authority to comment on politics. This is the wrong question. Public participation is the foundation of democratic practice, which makes room for all of us — English professors, waitresses, social workers, truck drivers, plumbers, politicians, and so on — to engage in civic discourse. While the Internet provides new and unique opportunities for this, the lack of sustained public debate, the erosion of public education, and the radical right’s manipulation of news create frightening challenges for participatory democracy.

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, American and European philosophers such as Walter Fisher and Jean-Francois Lyotard criticized the rise of scientific discourse and the decline of the narrative, claiming that this change diminished the capacity of ordinary citizens to make informed decisions. As an alternative, they both proposed a return to an understanding that our stories matter, that our stories are living, dynamic, and changing, and that our stories may, in time, change the world.

Mr. Alterman obliquely revives this movement, smartly attending to the function of story frames, or narratives, in the shaping of ideas and actions. What I missed in this book was the presence of stories, and for this reason, I felt the author missed an opportunity to more fully depict what’s at stake in our present political moment.

“Kabuki Democracy” is an important book, a nearly scientfic account of the forces that work against change. Astute readers of it will find that Mr. Alterman has two primary intentions. First, to educate us so that we understand the severity of the problems we face. Second, to teach readers that we can take action.

Yet, his description of the stakes may put some readers to sleep. What is needed is a live rendering of our problems that is grounded in fact and that does not veer into theater. Mr. Alterman accomplishes only the latter part of that proposition.

What is at stake has already become an everyday reality to many Americans and people around the world, a reality that most people on the East End of Long Island do not see regularly. It includes living in houses patched up with plastic bags when the roof collapses. It includes living surrounded by garbage when one does not have the money for gas to drive to the dump. It includes hungry people who go unfed. This is a stark contrast to the problems I hear about here — getting a reservation at the right restaurant or buying the latest iPhone.

The question of how to take action is also an everyday reality for many Americans and people abroad. Live within the confines of available resources. Follow ethical principles. Build community via public spaces and public events. Find joy in relationships rather than shopping.

Of course, such suggestions sound heretical because the past president told us we could solve our problems by going shopping. That didn't work. Mr. Alterman reminds us that it's time to try something else.

--

Eric Alterman lives in New York and East Hampton.

Stephanie Wade teaches writing at Unity College in Maine and spends summers in East Hampton.