Long Island Books: Here Be Monsters

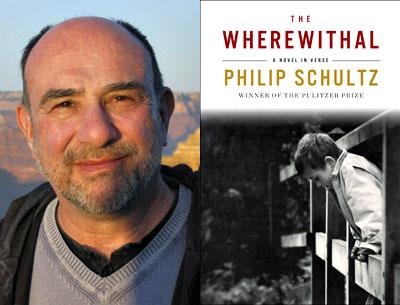

“The Wherewithal”

Philip Schultz

W.W. Norton, $25.95

Philip Schultz’s “The Wherewithal” is an ambitious, bracing book about large-scale suffering and small-scale guilt. Set in San Francisco in 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, the book inhabits several hells: two countries rent by war, a city bursting with the unemployed and terrorized by a serial killer, a German-occupied town in Poland whose citizens butcher their Jewish neighbors.

The narrator, Henryk Stanislaw Wyrzykowski, works as a clerk at a branch of California’s Department of Social Services, in a basement office packed with 700,640 files “recording every sort of grievance, indignity and plea for sustenance suffered in the Bay Area” between 1959 and 1968. The cases are closed and the caseworkers incompetent, or, like Henryk’s predecessor, tormented by the sheer “volume and onslaught” of misery.

As for Henryk, he is hiding from the precariousness of his present circumstances and the trauma of his past. He takes the job at the welfare office to dodge the draft and spends his days translating his mother’s diary, which records her struggle to hide seven Jews during the pogrom of 1941 in Jedwabne, Poland. Like Mr. Schultz’s narrative, the mother’s diary testifies to one person’s descent into madness and determination to find purpose in a world that every day appears “a little more off-kilter, a little less in its right mind.”

His mother’s courage shines a spotlight on Henryk’s own moral shortcomings, as Henryk contends with the ghost of Rossy, a childhood friend and the son of Holocaust survivors, whom Henryk accidentally kills in a game of William Tell. As his name (and one of the book’s many epigraphs) suggests, Henryk is a sort of Jekyll and Hyde, half-monster, half-man.

“Potentially are we all monsters?” Henryk wonders. Mr. Schultz’s answer is a resounding yes, and the acknowledgment of our collective guilt gives “The Wherewithal” its grim power.

With sinister irony, Henryk refers to himself as “snug as a bug” in his basement office, a phrase that underscores Henryk’s Kafkaesque situation and draws attention to Mr. Schultz’s poetic vocation; the phrase sounds a lot like Seamus Heaney’s description of a writer in his famous poem “Digging.” In Heaney’s poem the speaker honors his bucolic lineage while setting himself apart from it, trading in his father’s spade for a squat pen that rests between his finger and thumb, “snug as a gun.”

Yet despite being a novel-in-verse, “The Wherewithal” contains few poetic flourishes. The mostly skinny, largely free lines run ragged down the page, mimicking Henryk’s grief performance, and the fits of lyrical language (thoughts like “scattered dependents of an orphaned mind”; pleas like a “vast howling ocean wave”) often intrude on the narrative, as if to comment on the absurdity of making verse in the wake of 20th-century monstrosities.

As absurd are Henryk’s many short-lived jobs, including a stint teaching remedial speech to American veterans suffering from P.T.S.D. In a passage indicative of the book’s farcical-yet-agonized tone, Henryk interrupts a lesson on split infinitives to ask a student in a “drugged stupor” what he thinks of such grammatical rules.

“What de fuck?” says the student, rising to tower over the teacher before asking the more pressing (if predictable) question: “You ever kill a man?”

When guilt-ridden Henryk begins to sob, the student goes to comfort him. “Okay, man,” he says, “I know, we’re all just poor sick animals. . . .”

Everyone in “The Wherewithal” is, indeed, a poor sick animal. Their only purchase on redemption is got through compassion. Yet the book is as much about human compassion as it is about our incapacity to make something useful out of that compassion. Later in the narrative, asked why he has joined up with an assorted group of protesters, Henryk admits, “To prove my insanity and feel less futile.”

The one exception is, arguably, Henryk’s mother, the only character with the moral wherewithal to seek purpose in a mad, mad world, with the backbone to aid her neighbors and give witness. Toward the end of the book, Henryk comments, “Mother is perhaps the happiest person alive. She didn’t turn away, but stood there, eyes wide open, seeing everything. Her suffering was useful. . . .”

The rest of us, this relentless book suggests, are potential monsters, barely clinging to the “fragile filament of our humanity,” which is to say, dangling by a thread.

Will Schutt is the author of “Westerly,” a collection of poems published last year. He won the 2012 Yale Younger Poets Prize and lives part time in Wainscott.

Philip Schultz won a Pulitzer Prize for “Failure,” his 2008 poetry collection. He lives in East Hampton.