Long Island Books: The Importance of Being Important

Richard Ravitch, Johnny Carson, and Roger Ailes found importance by being useful. The authors of new books about them will be honored at Authors Night, the annual fund-raiser for the East Hampton Library, on Aug. 9.

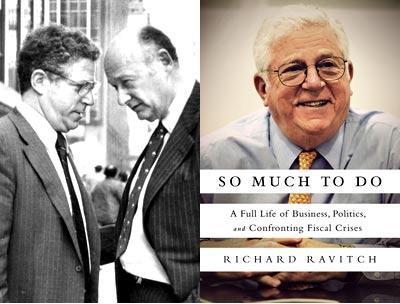

Richard Ravitch, in his rich and beguiling memoir, “So Much to Do: A Full Life of Business, Politics, and Confronting Fiscal Crises” (PublicAffairs, $26.99), presents himself as an affable, capable, smart, and dedicated public servant and successful businessman. He was an expert on public financing and construction of low and middle-income housing — his firm HRH built Waterside Plaza and Manhattan Plaza — and was head of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and lieutenant governor of the State of New York. (Full disclosure: We’ve met and have mutual friends.)

Mr. Ravitch has written an important memoir describing his many praiseworthy accomplishments in finance, business, and politics with candor, modesty, energy, and eloquence. He shows readers how he built trust and friendships amid conflict, strife, and disasters . . . and how his good will and faith in democracy and consensus-building led to practical solutions to virtually intractable public policy puzzles.

He was a grandson of Russian émigrés escaping pogroms, and his family founded a small contracting business making sidewalk gratings and manhole covers. HRH Construction built the famous Beresford and San Remo luxury apartment buildings on the Upper West Side, where Mr. Ravitch grew up and attended Columbia University. He fell under the spell of the noted intellectuals Jacques Barzun and Lionel Trilling, Richard Hofstadter and Henry Steele Commager, scholars and exponents of Western liberal democracy who “inspired much of what I would do in my life.”

A call for help from then-Gov. Hugh Carey brought Mr. Ravitch into the thick of financial consulting on the impending bankruptcy of the New York State Urban Development Corporation, which involved very complex political and human-relations problem-solving. This led him into New York City’s fiscal crises over its bankruptcy.

“Amid the consensus that the city should be an agent for social change,” he writes, “almost no attention was paid to the cost of this change . . . reflected in the city’s rapidly growing annual deficits . . . that made some form of insolvency inevitable. . . .”

Wearing a 25-pound police-issue bulletproof vest, he spoke to Fordham Law School graduates in 1982 about why their legal education was the best possible training for public service, and why public service was the best possible use of their legal education. He had been named chairman of New York’s then-dysfunctional M.T.A. (thus the vest), a four-year job he later described as “the most exhilarating of my life. Once again, I had been able to address a major public problem . . . to draw on many of the friendships and relationships I had developed over the years.”

He tells these intricate stories with verve and cliffhangers galore, and he names the boldface pubic personalities involved.

Here’s the difference between how business executives as opposed to government officials do their jobs. In business, the essential takes precedence over the trivial, so a wise businessperson will divide all tasks into the 10 percent that must be done immediately and the 90 percent that is to be placed on the back burner. Once the critical 10 percent is accomplished, the remaining back-burner 90 percent is then divided between a new critical 10 percent to do right away and a new back-burner remainder.

But government people think differently: They assume that perhaps 1 percent of the general public is dishonest, and so they make a government regulation specifically aimed at that 1 percent. Mr. Ravitch succeeded in his demanding jobs because he clearly understood the importance of both approaches.

Henry Bushkin’s “Johnny Carson”

Johnny Carson was a durable, amusing late-night talk-show host — a popular entertainer whose private life included such embarrassments as alcohol abuse, offensive behavior, and multiple marriages and affairs (simultaneously). He was a real-life Peck’s Bad Boy.

Henry Bushkin, a lawyer and Carson’s sometime protector, fixer, confidant, and wingman, has written a delicious tell-all biography (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $28) in which he reveals in amusing detail how he had to clean up “the mess” after all of Johnny’s naughty business and personal screw-ups.

Mr. Bushkin had become Johnny Carson’s best friend and lawyer for 18 years starting in 1970, when he was surprised to be tapped to be Johnny’s trusted right-hand man, although he was inexperienced in show business and merely 27 years old. He proved to Johnny that he could negotiate tough contracts with NBC, manipulate complex business deals with people who wished to invest in Johnny’s fame and name, bail Johnny out of difficult situations, and generally cover his misdeeds. Above all, he was loyal.

Mr. Bushkin says, “There are still . . . people around Los Angeles who had a business relationship with Carson that ended unhappily; they still love Johnny but hate the prick who was his attorney . . . just the way Johnny wanted it.” Although Johnny was endlessly witty and enormously fun to be with, he could also be the “nastiest son of a bitch on earth.”

Johnny’s bright side showed when he compared himself to the movie star Lassie: “We’re both lovable and we both come when we’re called.” Mr. Bushkin tells this story: Zsa Zsa Gabor brought her Persian cat to her guest appearance on “The Tonight Show,” and she asked Johnny if he would like to “pet my pussy.” He reportedly said, “I’d love to, if you’d just remove that damned cat.”

His darker side appeared when his producers thought a comedy writer for “The Tonight Show,” who was making $4,000 a week in the 1970s, deserved a raise, and Mr. Bushkin turned him down. He went directly to Johnny — who fired him on the spot. An example of Johnny’s pride involved a lawsuit he had Mr. Bushkin initiate against a company called Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets, whose slogan was “The World’s Foremost Commodian.” He was not amused. Mr. Bushkin says Johnny eventually spent $500,000 to win less than $40,000 in damages. (The case is often cited as an example of trademark protection.)

Citing the critic Kenneth Tynan in a New Yorker profile, Mr. Bushkin believed that Carson resembled the great Fitzgerald creation Jay Gatsby because both dreamed of self-made wealth and happiness, both had abundant energy, youth, and ambition despite humble origins . . . and both were profoundly lonely and empty of authenticity. (“If you can fake authenticity, you’ve got it made,” Sam Goldwyn reportedly said.)

Johnny did and had it made; he was crowned the “king of late night.” Not only that, five nights a week he essentially performed the equivalent of a somersault on a high wire: The jokes had to work, no rewrites, no retakes, and the high-powered guests (like Jack Lemmon, Gene Kelly, James Stewart, Joan Rivers, politicians) were without scripts, prepackaged lines, costumes, or directors . . . in effect he was naked before millions.

“The Loudest Voice in the Room”

Roger Ailes is a man with “unrivaled power to sway the national agenda,” a “brilliant, bombastic [guy] who built Fox News — and divided a country,” living a story worthy of “Citizen Kane,” according to Gabriel Sherman in his fascinating, unauthorized, courageous biography, “The Loudest Voice in the Room” (Random House, $28). A unique genius of conservative values, Mr. Ailes inhabits a world of outsize personalities like himself: Bill O’Reilly, Karl Rove, Glenn Beck, presidential aspirants, and Tea Party loyalists.

Although discouraged from writing this biography by Mr. Ailes himself (and by his loyal associates), nevertheless Gabriel Sherman has done a heroic job of research and scholarship by interviewing 614 people who worked with or observed Mr. Ailes during his five decades of public life. Mr. Sherman confirmed facts with a minimum of two sources, and had fact-checkers invest over 2,000 hours vetting his book for accuracy.

Mr. Ailes and his associates attempted to squelch his project and demean Mr. Sherman with a kind of disinformation campaign that described him as a “harasser” and “attack dog” and a “George Soros puppet.”

In 1996, Rupert Murdoch hired Roger Ailes to launch Fox News, and the liberal media establishment dismissed it as a joke. In 2012, under Mr. Ailes, Fox News was valued by a Wall Street analyst at $12.4 billion.

Mr. Ailes has said he built the operation from a news channel into a national phenomenon using “my life experience.” That included being producer of “The Mike Douglas Show,” a chatty 1960s daytime talk show where he learned commercial and entertainment methods of catching and holding viewers’ attention. As a consultant to Richard Nixon, he “adopted a sense of political victimhood and a paranoia about enemies. . . .”

Later he became an Off Broadway producer of “The Hot l Baltimore,” Lanford Wilson’s play about prostitutes, addicts, lesbians, lost souls, and losers, and created an artistic and commercial success: three Obies, a New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for best American play in 1973, and huge profits for its investors and famed producer, Kermit Bloomgarden.

In the 1980s, Mr. Ailes learned the “dark art of attack politics as a mercenary campaign strategist,” which he would later apply to turning Fox News into a money-making political powerhouse.

Mr. Sherman has done a fine job and a public service in bringing such a complex force of nature — warts and all — to life.

Richard Ravitch, who has a house in East Hampton, Henry Bushkin, and Gabriel Sherman will sign books at the East Hampton Library’s Authors Night on Aug. 9. Afterward they will be guests of honor discussing their work at fund-raising private dinners.

Stephen Rosen, a regular book reviewer and essayist for The Star, lives in New York and East Hampton.