Long Island Books: The Innovators

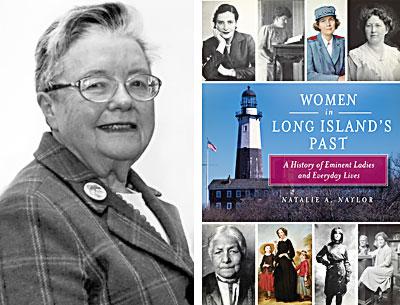

“Women in

Long Island’s Past”

Natalie A. Naylor

History Press, $19.99

Natalie A. Naylor, a Hofstra University professor emerita, has assembled a useful and much-needed reference work on women’s history. Her focus in “Women in Long Island’s Past” is on Nassau and Suffolk Counties, where she found the public contributions of the “Eminent Ladies” and “Everyday Lives” of her book’s subtitle, as well as those of other women worthy of note.

The earliest women addressed are Algonquians who participated in the sale and leasing of tribal land, activities revealed in 17th-century documents. The book ends with a chapter on historians and preservationists that sketches contributions of women from the 1930s to the 1980s. In this section, East Hampton’s Jeannette Edwards Rattray, who died in 1974, is noted for her many works on local maritime and community history.

The early chapters, from pre-European settlement times to the start of the Civil War, are most effective in placing the lives of individual women within the social and economic trends of the periods. Women played a role in events that led up to the American Revolution. For example, in the 1760s, in response to the English Parliament’s enactment of taxes on certain imports, women supported economic boycotts by refusing to purchase British goods. A 1769 Boston newspaper reported that in order to replace imports, “young Ladies at Huntington on Long Island . . . agreed to try their Dexterity at the Spinning-wheel” and spun many skeins of “good Linen Yarn.”

To support their families, some women became more engaged in work beyond the “domestic sphere,” in jobs made available by the expansion of commerce and the founding of new institutions. Wives helped their husbands run taverns, and, by the 19th century, women operated boarding houses. Through their churches, wives, widows, single women, and nuns raised money, nursed the sick, and taught school. Women even prepared the bodies of child and female victims of shipwrecks off the south shore of Long Island for burial.

In a chapter that is a transition from an integrated historical narrative to a concentration on individual women, Ms. Naylor documents the differing connections that five of the nation’s first ladies have had to Long Island. The first, Anna Symmes, had boarded in East Hampton while attending Clinton Academy around 1790. She served for only a few months before the death of her husband, President William Henry Harrison, in 1841.

Julia Gardiner married President John Tyler in 1844. She was born on Gardiner’s Island and grew up in East Hampton. She ended “her reign as First Lady with a grand farewell ball with three thousand guests.” In 1868, former first lady Julia suggested to President Andrew Johnson that portraits of presidents’ wives be hung in the White House. “Hers was the first to be hung.”

Two other first ladies associated with Long Island were Edith Kermit Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt. Finally, Jacqueline Bouvier, who was born in Southampton Hospital and had a grandfather who had summered in East Hampton beginning in 1912, served as first lady from 1961 to 1963 as the wife of President John F. Kennedy.

The last two-thirds or so of “Women in Long Island’s Past” concentrate on Ms. Naylor’s “Eminent Ladies,” or close thereto, in specific roles and work-force occupations. Among the biographical sketches of writers, editors, artists, philanthropists, and humanitarians is a profile of Margaret Olivia Slocum, who married the industrialist Russell Sage in 1869. Upon his death in 1906, she became one of America’s wealthiest women. Among her local projects, she helped fund Pierson High School, Mashashimuet Park, and the John Jermain Memorial Library, all in Sag Harbor.

The painter Lee Krasner was born in Brooklyn in 1908 and with her husband, Jackson Pollock, moved to Springs after World War II. Krasner died in 1984, having bequeathed most of her estate to establishing the Pollock-Krasner Foundation in support of visual artists.

Besides the “traditional occupations in the enlarged domestic sphere,” including nurses in hospitals and clerical staff in businesses, Long Island nurtured women entrepreneurs and scientists. Alicia Patterson and her husband, Harry Guggenheim, bought the “remnants of a defunct newspaper in Hempstead in 1940 and started Newsday.” After her husband was recalled to the Navy in World War II, Patterson managed the paper alone and remained its editor after the war. “Under Patterson, Newsday grew into the largest suburban newspaper in the country,” Ms. Naylor writes.

In science, Barbara McClintock, a geneticist who grew up in Brooklyn, joined the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1941. She received a Nobel Prize for her discoveries in 1983.

Among the innovators who chose a course that knowingly placed their lives at risk were Long Island’s “Pioneering Pilots.” To this reader, their feats are the most dramatic of those discussed in this book, even though they were probably not uniquely long-lasting in promoting the field of aviation.

During the first decade of the 1900s, early flights took place on Nassau County’s Hempstead Plains because the area was flat and treeless. Among the many aviators surveyed by the author, Bessica Raiche stands out: She was the first woman to fly over the Plains, in 1910, and was proclaimed the First Woman Aviator of America. These were among the activities that led to the development of Long Island’s aircraft industry. During World War II, about 30 percent of the employees at Grumman Aircraft in Bethpage were women and roughly 60 percent at Republic Aviation in Farmingdale.

Long Island’s wealthy women who were innovative in their thinking stood out in the movement to achieve women’s suffrage. They were “Socialite Suffragists.” Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont, a divorcee in 1895 with a large financial settlement, devoted much of her fortune and time to women’s suffrage after the death of her second husband. She worked in Newport, R.I., and New York, where she founded the Political Equality Association. Belmont organized a branch of the organization on Long Island in 1911 and remained active in the suffrage movement until the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote nationwide. That same year, civic activists organized the Nassau County League of Women Voters.

Many women trained as librarians. Among them was Ernestine Rose, who was born in Bridgehampton in 1880. A graduate of Wesleyan, Rose received her library degree from the New York State Library School. She served many years at branches of the New York Public Library, among them the Harlem Branch. She became a leader in the founding of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Historical preservation and museum support engaged many women on Long Island and Ms. Naylor identifies them throughout the book. House restorations and schoolhouse museums are placed in their historical contexts. An example is Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island and its late owner Alice H. Fiske, whose husband was a descendant of the 1652 Sylvester settlers.

Extensive and detailed endnotes close out the book. They will be helpful to general readers and to researchers. An index would have been useful, although its need is mitigated by the division of the book into topical chapter and subchapter headings and by the brevity of the text.

Ann Sandford is the author of “Grandfather Lived Here: The Transformation of Bridgehampton, New York, 1870-1970.” She lives in Sagaponack.