Long Island Books: The Journal Ascendant

Reading Warren H. Phillips’s new autobiography, “Newspaperman: Inside the News Business at The Wall Street Journal,” I was reminded of the expression commonly mistaken for an ancient Chinese curse — “May you live in interesting times.” Once one comes to understand that these words are neither ancient, Chinese, nor a curse, it becomes easy to appreciate them as a good wish, something to be made the most of. That is exactly what Mr. Phillips does.

The son of an immigrant father of modest means, he was single-minded, from childhood on, in his ambition for a career in newspapers. In his first job, as a copyboy for The New York Herald Tribune, he earned $16 a week. Most of his career was spent at The Wall Street Journal, from which he retired in 1991 as publisher and C.E.O. of its parent corporation, Dow Jones & Company. The parallel rises of Mr. Phillips and The Wall Street Journal itself were a heady experience that certainly made for “interesting times.” These Mr. Phillips chronicles in this very well-written volume.

Following his graduation from Queens College in 1947, Mr. Phillips sought jobs at several New York City newspapers, with no success. “Last on my list of New York newspapers . . . was The Wall Street Journal, ” he writes. “It was then a thin, one-hundred-thousand-circulation financial paper downtown at 44 Broad Street . . . just south of Wall Street. There my luck changed.”

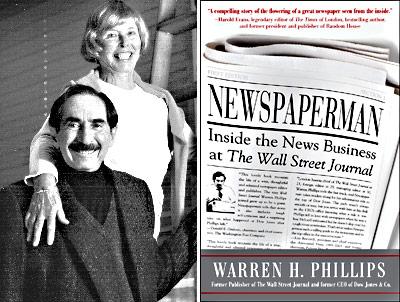

“Newspaperman”

Warren H. Phillips

McGraw-Hill, $30

And there, also, his career began. By the time he became the paper’s managing editor nine years later, the author had served as a foreign correspondent in several world capitals, its foreign editor, and its regional editor in Chicago. Along the way, he became imbued with The Journal’s uncompromising standards of honesty, integrity, and high-quality writing. (He quotes a Journal colleague as saying, “There is no such thing as bad writing. Only bad thinking.”) Indeed, a 1969 Harris Poll called The Journal “the most trusted newspaper” in America.

When, at the height of the cold war, the C.I.A. pressed Mr. Phillips to allow it to place bona fide journalists in the paper’s Moscow bureau who would also be spying for the agency, he categorically refused. Not that he was unsympathetic to the request or unwilling to help his country. Rather, “I rejected their overtures for completely different reasons of conscience and practicality,” he states, elaborating that if the Soviets learned that even a single Journal correspondent was also a C.I.A. agent, it would jeopardize the safety of every other Journal correspondent in Eastern Europe. “This I was not prepared to do.”

The major portion of Mr. Phillips’s story is the story of The Wall Street Journal and Dow Jones themselves for the 44 years he worked there. From his privileged vantage point, we witness exactly how his newspaper grew into a major international journalistic presence and how — toward the end of his career there — the signals were clear that the supremacy of print journalism was coming to an end. Though ultimately loyal to The Journal and to Dow Jones, Mr. Phillips is not unwilling to reveal their faults and blemishes, along with their strengths and successes. In a thoughtful epilogue, he shares his wisdom on The Wall Street Journal’s 2007 sale to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation.

Spending virtually all of one’s career under one corporate roof causes one to feel like a member of a closed universe, knowing all the other members of that universe in person or as part of the corporate lore. While the author’s apparently encyclopedic knowledge of The Journal and Dow Jones will make this book most appealing to the other members of that particular universe, that is by no means to say that it lacks universal appeal to anyone interested in news and the news media of the last 60 years.

Moreover, spending virtually all of one’s career under one corporate roof and reaching the top of the corporate ladder — that’s what turns someone into what used to be called “a company man.” And that is what Mr. Phillips is, though I don’t intend this as a criticism. By so artfully combining the story of his life with the story of the enterprise he served well for so long, he maintains an admirable personal modesty in the light of such impressive professional accomplishment.

—

Warren H. Phillips lives in Bridgehampton.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.