Long Island Books: Life With Dad

“They’re having a kid? His life’s over.”

I heard those only half-joking words at a summer barbecue a few years ago. It took me a while before I could complete the thought: “And a new, richer one begins.”

What’s nice about “Pobble’s Way” (Flashlight Press, $16.95) by Simon Van Booy is that on a winter walk a father’s flights of fancy match his daughter’s, and the two play off each other. To him, a leaf is a butterfly raft. To her, a mushroom is a frog umbrella.

And the exercise in imagination extends to a menagerie of woodland animals who, in a furred and feathered Rashomon effect, take turns deciphering what a dropped pink mitten actually is. The options: cotton candy, a mouse house, a wing warmer, a fish coat, or a carrot carrier.

Mr. Van Booy, originally from Wales but a South Fork resident-slash-visitor ever since he earned an M.F.A. at Southampton College, is the author of a recent debut novel and story collections that range from well received to prizewinning, and the language here is fresh: The duck comes “strutting over to the Something”; the mouse “parked her plump body” on top of it. Or simply fetching: “Dusk had stilled the creaking trees, the branches wore long sleeves of snow. . . .”

There’s comedy, too. A mitten? “ ‘Never heard of it,’ Mouse muttered.” Rabbits are accused of engaging in gluttony when it comes to carrots? “ ‘Some do, I suppose,’ Bunny said, looking at her paws.”

Wendy Edelson’s illustrations, in watercolor glaze, capture the woods’ profusion of life. She hails, not surprisingly, from Washington’s Bainbridge Island, where the wildlife is indeed wild and the greenery so green it practically throbs.

She includes charming endpapers showing where each of the animals makes its bed. Which is where they retreat to as the story, set after dinner but before bedtime, comes to hint at the eternal parental struggle to get a child to sleep.

And the moon “pulled her white blanket across the woods.”

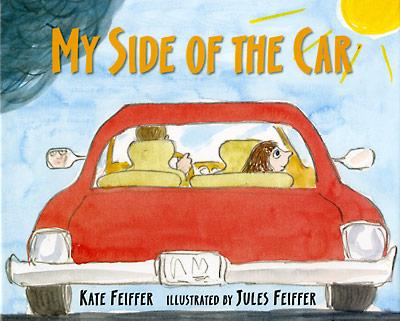

“My Side of the Car”

At last, a kids’ book that explores life in the car. It occupies so much of a parent’s time, energy, and worry — from negotiating harnessed safety seats worthy of the Space Shuttle to the use of rolling motion as sleep inducement, and what do you do when the kid’s asleep and you have to run an errand? — you’d think they’d have proliferated like so many side-impact air bags.

“My Side of the Car” (Candlewick Press, $16.99), by Kate Feiffer with deft pencil-and-watercolor illustrations by her father, Jules Feiffer, is about a long-delayed trip to the zoo that gets put off yet again by rain. Complication ensues when little Sadie notices that it’s falling on only the driver’s side of the car. Her dad splashes through puddles and can barely see past the wipers, but out Sadie’s window it’s all garden parties and sunflowers.

(The whimsical book, based on an actual argument the two once had in trying to get to a nature preserve on Martha’s Vineyard, is one of a number of projects the cartoonist had lined up for himself when he holed up in a rental off a quiet Southampton street not long ago.)

Is it merely wishful thinking? To investigate, Sadie steps out of the car and into mud up to her pink stockings. On his side, anyway. She relents.

But one good turn deserves another, and they don’t get far before the sunshine crosses the (psychological?) divide, enabling father and daughter to stride happily into the zoo together. At last.

“Orani”

You won’t find a lovelier children’s book than Claire A. Nivola’s “Orani” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $16.99). It tells of a family trip she took close to 60 years ago back to the village on Sardinia where her father grew up. (Her father being the artist Costantino Nivola, who kept a house in Springs for many years.)

Like magpies, she and her Sardinian cousins “flew and settled wherever something was happening” in Orani, a small place of stucco and red tile roofs ringed by mountains. The sheer immediacy of life there renders her experiences indelible. “All I needed to learn and feel and know was down there,” she says from a perch overlooking the village.

She eats fruit and figs right off the tree. Women bake bread communally at night to avoid the heat of day; neighbors make the cheese and honey. She walks the streets and through open windows hears plates being cleared. Among the sights are a three-day wedding celebration, a nearby newborn, and, in a second-floor room open to children, a corpse laid out for a funeral, “his face rigid and white and cold with the unspeakable strangeness of death.”

She finds her return home to crowded New York City, with its height and symmetrical layout, equally strange. The book ends with her wondering what different worlds so many people might have come from. It’s a passage with all the feeling, hope, and generosity of a prayer.

Their own Oranis? They should be so lucky.