Long Island Books: Love and Its Risks

“Grand Isle,” Sarah Van Arsdale’s absorbing and suspenseful new novel, takes place in an eponymous North Fork enclave that closely resembles Shelter Island. A rather large cast of characters, most of them summer residents of Grand Isle, are introduced early on. It’s to Ms. Van Arsdale’s credit that they’re all clearly differentiated and pertinent to the tragedy at the heart of the story: an accidental death and its cover-up that create a ripple effect in the island’s close-knit community.

____

“Grand Isle”

Sarah Van Arsdale

Excelsior Editions, $21.95

____

The teenagers in the novel, with their emotional liability and lapses in judgment, are particularly well drawn. Cort is spending the summer following his freshman college year with his newly remarried father. He’s haunted by memories of childhood vacations spent in the same Grand Isle cottage (before extensive renovations) with his original, intact family. Now, he’s an interloper on a honeymoon, a restive boy driven by surging hormones and divided loyalties.

In stark contrast, Cort’s friend Damian, who’s been raised by a spirited single mother, is stable and ambitious, and less morally ambivalent. He’s had a serious relationship with a young woman — a fellow student back at Reed College — with whom he’s exchanging “phone calls and real letters on paper” during their summer separation, rather than the usual e-mails and texts. Damian has equally serious career plans, but he’s been keeping a secret from his mother about his health.

Kylie and Betheny, the two immature local girls with whom the boys hang out, are sick of their dead-end supermarket jobs and eager for adventure after “a crappy, boring winter.” As Betheny announces, “It’s summer! Time to get crazy!” That seasonal craziness is what leads to the auto accident in which Damian is killed, and to its spiraling aftermath.

Damian’s mother, Franci, sinks into a quicksand of grief that doesn’t preclude her growing suspicion that the facts of her only child’s death are not as they are reported. Indeed, a loose conspiracy conceals the truth about what happened that fateful night, and the frustration of not knowing only adds to Franci’s anguish. Her coterie of friends, especially Peg and Tessa, conspire to console her, to surround her during those first horrific days and nights of mourning.

Peg is securely married to Torsten, while Tessa, at work on a scholarly book, grapples with wavering feelings about her mercurial lover, Jake, a restorer of rare violins. Jake, the owner of the house he and Tessa share on Grand Isle, is in a position of power in their relationship. And he uses that power to seduce and manipulate her. He’s jealous of Tessa’s friendship with Kenji, the island’s pharmacist, and dismissive of her passion for gardening. “Flowerbeds are overrated,” he tells her. “All that work and nothing to eat.” But Tessa tries to focus on moments of romantic and sexual happiness with Jake, and generally considers herself both “fortunate” and “undeserving.”

Franci isn’t the only one who questions the validity of the statements made on the night of the accident. “Cop Callahan” keeps going over the testimony of everyone involved. The official accounts remain fairly consistent, but other versions of the event are casually leaked by Kylie to Rick, an opportunistic hustler and petty thief, who isn’t above using blackmail, with a particularly sadistic edge, to get what he wants.

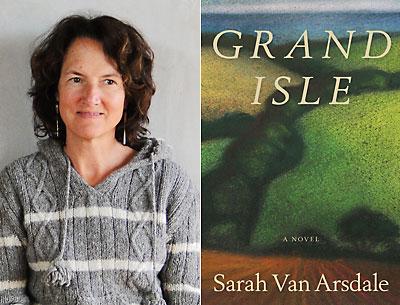

Ms. Van Arsdale, who won the Peter Taylor Prize for her novel “Blue,” is also a poet and essayist, and her depiction of place is often lyrical and dead-on. The shore “wraps around Grand Isle like a cupped hand,” and Tessa “watches the first sun ignite the flowerbeds.” The same economy and eloquence bring Damian to flickering, poignant life before his demise, “diving off the raft, plunging into the water in his final, most perfect dive, a streak of boy, airborne for one moment, then gone.”

“Grand Isle” incorporates several interwoven subplots, all informed by the central event of Damian’s death and most of them successful. Cort’s father’s marriage to his prototypical younger, prettier second wife never falls into cliché. She tries, with ineffectual sincerity, to befriend her unhappy stepson while fumbling to find her own place in a long-established society. The abrupt departure, shortly before Damian’s death, of the woman Franci loves serves to deepen her misery and our sympathy. And the enviable ease between Peg and Torsten is deftly complicated by a hidden history of infidelity.

Only Tessa’s story creates a problem of credibility. As Jake becomes more controlling and cruel, she invents excuses for him and for her own apathy. Although people do stay in abusive relationships out of inertia or fear, Tessa’s inability to leave Jake finally strains the reader’s patience. Then there’s the matter of the orphaned baby raccoon she finds in the shed on Jake’s property and furtively feeds and protects against his plans to trap and kill it. Her own sense of abandonment and guilty relief over a miscarriage may account for her identification with the animal, which could be rabid, but her persistent efforts — with Kenji’s help — to rescue it seem improbably reckless.

Franci and Cort are the most compelling players in “Grand Isle,” although the former proves to be fiercely strong and the latter essentially weak and vulnerable. Franci’s grief is palpably rendered. She imagines it “like a plastic skin over her skin, her clothes, mottled, clear, puffy like the skin of someone who’s been badly burned and won’t survive.” Yet she manages to pull herself up out of its depths to search for the truth and thereby find some justice for her lost son “alone in the world of the dead.” In a chillingly atypical yet believable act, she collects shards of glass from the accident and mails them anonymously to someone she suspects is lying about it.

Cort, too, is never one-dimensional, especially when he struggles with his own sense of loss and with his conscience. “He just leans back in the chair, and here comes the feeling of Damian, more than a memory, or a vision — it’s so huge inside him that he feels he can barely contain it. It’s some kind of longing, and some kind of pain, all of it gathered up into one big tornado of feeling, spiked with his shuddering anxiety.” Cort and Franci each ace E.M. Forster’s test of a “round” character, defined in “Aspects of the Novel” as being “capable of surprising in a convincing way.”

The catalyst for Franci’s recovery is the unexpected appearance on the island of Damian’s girlfriend, Phoenix. Estranged from her own family and concerned because she’s stopped hearing from Damian, she shows up at his house, looking for him. It becomes Franci’s task to break the terrible news and to provide comfort in the midst of her own bereavement. She even takes Phoenix into her home.

But giving the girl shelter is not a purely altruistic act. “This is why Franci likes having her around. Phoenix keeps telling her things about Damian, things she didn’t know, and no matter how small these things are, Franci wants to hear them. Everything.” She doesn’t share any of this with Peg and Tessa, though, and they’re startled and troubled by their friend’s sudden desire to be “alone.”

Phoenix has news of her own — she’s pregnant with Damian’s baby — which she gradually admits to herself and then to Franci, who handles it with tempered joy. This might have served as a simple plot convenience, a greased path to a happy ending, but the pregnancy seems inevitable rather than merely predictable, and it brings its own element of suspense. There’s a question about the viability of the fetus, and worry that Damian’s medical problem might be genetic. Franci tells herself that “the fetus is yet just a cluster of cells still puzzling into a recognizable form,” and she coolly lays out all the options available to Phoenix, including abortion and adoption, encouraging her to make her own decision, while thinking, “keep it, keep it, keep it.”

Throughout the book, a pack of wild dogs roams Grand Isle. Tessa hears their howling, like a distant warning, when she and Jake are making love. Cort equates the dogs’ stealth with Rick’s. And Kylie, walking alone on a dark road, feels physically threatened by the nearby pack, a fear she’s unable to shake.

While the island’s feral dogs may represent the uneasy cohabitation of wildlife and humans, they also seem to symbolize the dangers inherent in the lives of the novel’s characters. Separately and collectively, most of them face up with courage to the consequences of secrecy and the risks of love.

Ms. Van Arsdale noted in an interview that it took her five years to write “Grand Isle” and seven additional years to find a publisher for it, which says more about the sorry state of publishing than it does about this author’s considerable talent and her affecting novel.

—

Sarah Van Arsdale teaches creative writing at the City University of New York and New York University.

Hilma Wolitzer’s most recent novel is “An Available Man.” She and her husband divide their time between Manhattan and Springs.