Long Island Books: Man of the Boards

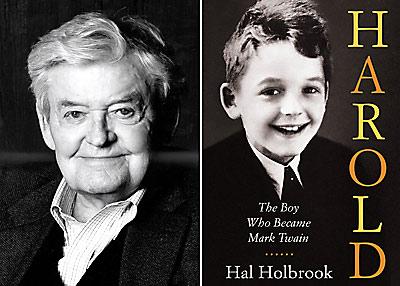

Actors — talented actors, that is — are usually amusing raconteurs and often good writers. They have a love of language, the sensuous savoring of the perfect phrase, and they develop a feeling for the dramatic arc of a scene, the timing of a punch line. So it is not surprising that Hal Holbrook, in his autobiography, “Harold: The Boy Who Became Mark Twain,” relates an arresting and vividly told life story, both personal and professional.

His personal story is tragic. He and his two sisters were abandoned as babies by their mother, who in her 20s fled family obligations for New York to perform in the Ziegfeld Follies and then in George White’s “Scandals” revue. She later went to Hollywood and after that the children never saw her again.

Their father, too, was largely absent from the family, unless he needed money. He led a vagrant’s life, often in and out of institutions to which his own father committed him. Harold’s grandfather was a successful businessman of old-school values and, fortunately for the children left in his care, an anchor for them during their childhood years. He died when Harold and his sisters were in their early teens, leaving them adrift in the care of their erratic, self-centered grandmother.

Harold, in accordance with his grandfather’s dying wish, was sent to Culver Military Academy in Indiana to remove him from the emotional turmoil of family life. At the academy a pattern emerged. He initially tried to fit in but then, instead of choosing sports and running track, for which he was being trained, he inexplicably joined the small group of “weirdos” studying in the theater program. It was his first taste of the terror and exhilaration of being onstage, and he became hooked. He later chose to go to Denison University in Ohio because he was attracted to the theater arts program, headed by Ed Wright, who would become his mentor and lifelong friend.

Inducted into the Army toward the end of World War II, he turned down a chance to enroll at West Point because the four years required would have delayed the start of his acting career. He describes himself during this period as a bundle of quirks and twitches, and perhaps the need of an insecure boy to disguise himself behind greasepaint, fake eyebrows, and luxuriant beards partly explains his early addiction to the theater.

____

“Harold”

Hal Holbrook

Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, $30

____

If ever an actor deserved his eventual fame it is Hal Holbrook. He, together with his first wife, Ruby, put in a grueling apprenticeship. At the time there were booking agents for various levels of touring, the lowest rung being the school assembly circuit, in which “educational” material was performed for schools, often in rural areas of the country.

Hal and Ruby had cobbled together a show consisting of two Shakespearean scenes, several historical and literary vignettes, and a final scene depicting a humorless journalist interviewing Mark Twain. To perform them, they had to provide and pay for the makeup, wigs, period costumes and props, publicity posters, tickets, and the means of transportation.

On their first tour they were booked into schools throughout Oklahoma, Arkansas, and the Texas Panhandle. They would often do three performances a day, starting in a high school auditorium or basketball court at 8 a.m., doing a second show at 10 for the seniors, and ending with a late-afternoon performance at another school after racing on back roads 50 or more miles to get there on time. The descriptions of the kids in these remote farming communities, face to face with “culture” for the first time, are both hilarious and heartbreaking.

After a year, Hal and Ruby graduated to the women’s clubs and college circuit, acting for audiences that actually listened. They logged thousands and thousands of miles in their station wagon, crisscrossing America to various venues.

For anyone interested in an unglamorous, nitty-gritty view of the theater world, this book is a rich, entertaining resource. I was struck by the detailed recounting of each performance and the obsessive tracking of the dollars earned. The money was a matter of survival, and they were hanging on for dear life. The repetitive nature of their efforts is, however, exhausting reading and could have done with some judicious editing.

Holbrook’s deepening interest in Mark Twain came about slowly. He began to more fully appreciate Twain’s humor, to go beyond the trappings — the white suit, the white hair and mustache, and the odd walk — and to identify with his thinking. When Ruby got pregnant, had babies, and had to quit touring, the marriage became strained. As a self-protection, Holbrook developed the Mark Twain portion of their show into a solo performance piece.

He presented it first in a New York nightclub, Upstairs at the Duplex, on a bill with the singer Lovey Powell. He was seen there by Ed Sullivan and given a spot on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Television made him visible to a larger audience and this led to his being asked to appear on the “Tonight” show with Steve Allen.

From then on, bookings tumbled into his lap — well-paid bookings. Once more he would drive endless, incredible miles across America, this time alone. He used the time to read more about Twain’s life, write, and try out new material, inserting gems sprinkled with laugh lines. He was gaining invaluable performance experience. He assembled, by trial and error, a full-length show and began to dream of Broadway. In between touring engagements he returned to New York, newly confident, and set up an office with a friend and co-producer, John Lotas, to hold backers’ auditions and look for a theater.

The autobiography might have ended with his triumphant opening on Broadway and his savoring of the universally excellent reviews, but he adds a postscript. It is 1959 and Hal Holbrook is 34, at a midpoint in his life. He looks back at what he has gained and what he has sacrificed to his driving ambition, acknowledging that he has been egregiously self-involved. He has many friends but his family life is, to quote him, “a mess.” He harbors a deep bitterness over the callous rejections he has endured from people like Lee Strasberg and the Actors Studio coterie.

All the same, his acting career was then finally on track, with many chapters still to be written. The climb had been arduous but the trajectory was clearly upward. Above all, he achieved what he set out to do — he established himself as a well-regarded member of the acting profession.

—

Hal Holbrook had a house in Amagansett for many years.

Jennifer Hartig left England in 1958 to star in “Jane Eyre” on Broadway opposite Errol Flynn. She lives in Noyac.