Long Island Books: Montauk, the 300-Year War Zone

“American Gibraltar”

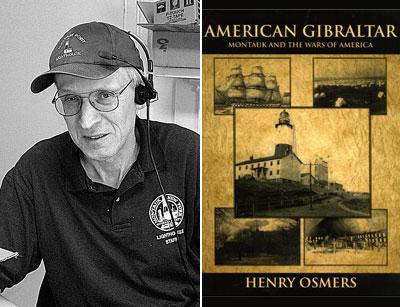

Henry Osmers

Outskirts Press, $21.95

Few would guess that the 11,000 acres of scrub oak and pine that we call Montauk can boast a history as complex as a small country’s. In “American Gibraltar: Montauk and the Wars of America,” which covers 300 years, Henry Osmers chronicles the regional repercussions of eight conflicts, from the Indian wars to the cold war years. Owing to its strategic location, Montauk has intersected with our war history and made one of its own.

The book is fully annotated, handsomely illustrated, and well written. It would be hard to find a more qualified historian. Mr. Osmers has written often of Montauk and the Montauk Point Lighthouse. His book “They Were All Strangers: The Wreck of the John Milton at Montauk, New York” came out in 2010. “American Gibraltar” is a goldmine of research, rich with anecdotes, quotations, and colorful detail. Its large paperback format nicely accommodates a host of archival photos and other artwork. There are 73 images in a book of 134 pages.

These sometimes distant wars altered the landscape from afar and gave Montauk special purpose. Whether a tent city for quarantined soldiers or a yacht club converted to a Navy base, U.S. military actions had a variety of effects. Such a history for an isolated peninsula is as unlikely as it was transforming.

We learn of a Montauk cleared of trees for a vast pastureland for 4,000 head of cattle and 2,000 sheep. The settlers who arrived in East Hampton in 1648 brought with them their farm life. The native Montaukett tribe not only accepted their neighbors but also taught them how to survive by hunting, fishing, and harvesting whales. It was a reciprocally protective coexistence.

But the maritime tribe had something other tribes wanted: wampum, ornate, finely wrought beads made from seashells and used as currency in trade between tribes. Montaukett wampum was the most coveted of all. According to another Montauk historian, Richard J. White, “Montauk . . . was considered the ‘mint.’ ” The Narragansett and Niantic tribes across Long Island Sound would kill for wampum, and did. The Indian wars weakened the Montaukett nation. By 1659, an epidemic reduced the tribe by two-thirds.

It was among the settlers of East Hampton that the Montauketts took refuge. As Jeannette Edwards Rattray wrote, “not a drop of blood was ever shed in anger between the Montauk Indians and their new white neighbors.”

Montauk saw the construction of only four houses by 1796. The fourth house included the building of the Montauk Point Lighthouse, which has since spared countless ships from disaster. The celebrated Third House, reconstructed in 1806, would serve as headquarters for Col. Theodore Roosevelt during the Spanish-American War. Thereafter, Montauk was described as “a natural Gibraltar, on a small scale.” Soon after that war, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle declared Montauk to be “a natural stronghold.” The aptness of the title “American Gibraltar” gathers weight one war after another.

We find the royal English fleet bristling with cannon in Gardiner’s Bay not once but twice: during the American Revolution and again in the War of 1812. Livestock presented an irresistible food source for the British fleets. In the spring of 1776, a battle off Montauk Point aborted a British attempt to steal cattle and horses. In September 1780 the royal fleet anchored in Gardiner’s Bay included eight men-of-war carrying, collectively, nearly 400 guns and thousands of men to feed.

The Spanish-American War brought both celebrity and compassion to Montauk. In Havana, the sinking of the battleship Maine triggered a war that would transform and publicize Montauk as never before. Tropical Cuban hostilities made for a bloody, disease-ridden conflict. If Spanish gunfire didn’t find American soldiers, malaria, typhoid, or yellow fever often did. Sick and wounded American combatants left Cuba by the shipload, bound for Montauk.

Teddy Roosevelt was the inspiration for a hospital and vast quarantine facility named Camp Wikoff at Montauk. Even before it was completed, the camp began receiving the first of 30,000 casualties. Photos reveal a tent city infirmary and T.R. himself, astride a sturdy mount.

This war extended the railroad and brought a new post office, a general store, the telegraph, and later the telephone. (When telephone service arrived, nine homing pigeons were also installed at the Montauk Lighthouse.) A power station and electric light came along, and so did two new restaurants. Local citizens, especially the women of East Hampton, took nourishment and much-needed supplies to the suffering men. Out of Camp Wikoff’s 30,000 wounded, only 263 died there.

Between the world wars, a National Guard training ground known as Camp Welsh came to Montauk. “The reverberation of guns fired by the artillery units . . . could be felt as far as fifty miles away,” writes Mr. Osmers. “Almost every summer, the Navy conducted target practice in Gardiner’s Bay.” Great warships like the Pennsylvania, the Nevada, and the Arizona unleashed fusillades from 14-inch guns.

During World War II, Mr. Osmers writes, “the majority of torpedoes that were sent to war ships, cruisers, and torpedo boats came from Sag Harbor.” Dirigibles occupied massive hangars at the Naval Air Station at Montauk. The area was considered an invasion point and was made part of the Eastern Coastal Defense Shield. These chapters of “American Gibraltar” are especially generous with old photos and revealing captions.

Camp Hero at Montauk became the main facility, with posh Montauk Manor serving as barracks for G.I.s. The government appropriated 468 acres, and Montauk was suddenly a military town. The Montauk Yacht Club at Star Island became a Navy auxiliary base, and private yachts became patrol boats. The Coast Guard used the restaurant magnate Howard Johnson’s yacht to search for subs. Much of Camp Hero’s military presence was disguised behind the facade of a mock fishing village. Quaint clapboard siding was actually four-foot-thick cement. The gymnasium appeared to be a church.

Boats, seaplanes, and lighter-than-air craft patrolled the coastline from Fire Island to Nantucket Shoals. Vulnerability of attack by sea demanded gun emplacements, better communications, new defenses, and men to man them.

They would come none too soon. Germany invaded Poland in 1939. And only 14 months after Pearl Harbor, a German U-boat would torpedo a Panamanian tanker 60 miles off Montauk.

By June 1943, huge 16-inch gun emplacements became part of Camp Hero. Vinnie Grimes, a lifelong resident, remembers the time well: “You had the Coast Guard up at the lighthouse, the Navy at Fort Pond, the Army at Camp Hero, the Signal Corps. . . .” From his house on Sandpiper Hill, Mr. Grimes remembers seeing “the flashes out in the ocean — it was German U-boats hitting tankers and cargo ships. . . .” Montauk’s new gun batteries could blast 2,240-pound projectiles across 30 miles of ocean with accuracy.

With the cold war, Montauk was among the first early warning defense sites. The guns of Montauk were dismantled and radar domes for Norad, the North American Aerospace Defense Command, went up. You could track the sophistication of advancing military technology by watching its evolution at Montauk. Before long, satellite technology would make shore defenses obsolete.

Montauk the geographic anomaly was made remarkable by people who coped with extremes. Real-life characters give this book heart because of the author’s humanistic style in the relaying of countless events. He shows how the consequences of war were answered with strength, intelligence, compassion, and invention.

As if nothing ever happened, Montauk has returned to a relatively pristine state. But its imprint on America’s military history remains indelible. War is about courage, resourcefulness, and nationhood. Patriots propel Mr. Osmers’s narrative from the beginning, and patriotism infuses it to the end.

Henry Osmers is the tour director and historian at the Montauk Point Lighthouse. He lives in Shirley.

Jeane Bice, who lives in Springs, is writing a book about life and death in small-town New York.