Long Island Books: More Than the Eye Can See

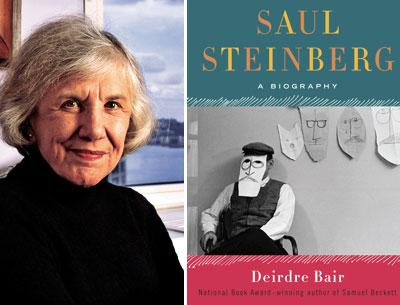

“Saul Steinberg:

A Biography”

Deirdre Bair

Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, $40

Saul Steinberg’s sharply ironic drawings became so well known in the 20th century that the term “Steinbergian” was readily understood as a reference to a perceptive and piercing wit that stemmed from some slightly off-kilter way of looking at the world.

Probing the mind behind this art, in the format of a biography, would seem to be an inevitable endeavor. There is much to suggest that Steinberg thought so too, for he saved every souvenir of his life and arranged for his archive to be deposited with the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale. This and other archival accumulations plus recollections gleaned from many interviews provide content for an insightful narrative that can seem edgy at those moments when aspects of his personal relationships are pushing norms of social behavior, or when Steinberg’s myths about himself come into play, or when the reader confronts excessive amounts of the artist’s own documentation of the churning neuroses in his life.

Deirdre Bair has previously proven her talent for examining a life and making details yield meaning. Her biography of Samuel Beckett won a National Book Award and her biographies of Simone de Beauvoir, Carl Jung, and Anais Nin also received prestigious honors. In choosing to write about Steinberg (1914-1999), whose drawings (especially those appearing in The New Yorker and on its covers) she had long collected in printed form, Ms. Bair once again took on the challenge of chronicling a deeply introspective achiever possessing very unusual creative sensibilities.

Ms. Bair weaves her research and wealth of material adroitly — although at times exhaustingly — as she recounts Steinberg’s roots in Romania; the anti-Semitic experiences of his boyhood, which he forever blamed for his haunted persona; the swift recognition of his talent in Italy and then America; the difficult escape from Europe in 1941; wartime service in an information unit of the United States Navy; the income generated by the reception to his art; every type of personal or business interaction; the marriage to Hedda Sterne; the attachment to his house in Springs; the tortuous 35-year relationship with Sigrid Spaeth; therapeutic travels; sexual escapades; anxieties, obsessions, and depressions.

Many will appreciate the author’s alertness to sources for specific imagery Steinberg repeated often, even as he processed new observations about new regions. There were experiences during his early years in Europe, for example, that influenced the artificial diplomas, false certificates, seemingly official government seals, tiny rubber-stamp figures, fanciful maps, pseudo-paper currency, postage stamps, marching soldiers, people fashioned from fingerprints, and elegant but undecipherable script.

Always penetrating, Ms. Bair suggests that a certain frequently used stylized female aligns with the artist’s domineering, hypochondriac mother, Rosa. His father, Moritz Steinberg, collected wooden type and reproductions of famous paintings for his ornamented box and decorative arts factory in Bucharest, and takes a significant role among the formative sources for his son’s pictorial quotations.

There is also rewarding background relating to the way Steinberg’s drawings can make buildings yield particularly strong messages. His use of Art Deco characteristics stems, tellingly, from his impressions of Miami, where he first entered the United States as an immigrant in 1942. More hints of the role buildings had in shaping his special sensibilities are found in his energizing years enrolled in the architecture program at Regio Politecnico in Milan. He made the effort to take final exams and complete his degree requirements only when Italy’s new restrictions on Jewish students became a threat to graduation.

He credited the launch of his unusual skill with a pencil, then pen, to a Politecnico drawing professor who instructed him to “show something more than what the eye can see.” In interviews for an autobiographical manuscript, Steinberg further explained that he found himself “retaining the attitude of a child, looking at the external world as if for the first time.” (As one of her sources, Ms. Bair uses this manuscript, prepared by the artist’s lifelong friend from the Regio Politecnico years, Aldo Buzzi. Selected excerpts were published by Buzzi as “Reflections and Shadows” in 2002.)

At least one famous New Yorker cover featured a mystical, watery horizon that Steinberg often repeated, and Ms. Bair emphasizes his use of Louse Point in Springs as the basic source. The site is a short bicycle ride from the home on Old Stone Highway that he purchased in 1959 and left to his niece and nephew at his death. Occasional alterations to the property form part of the narrative, especially Steinberg’s addition of a larger studio.

The artist’s commercial commissions are discussed with considerable detail, providing information about his handling of copyright, contracts, reproduction rights, publishing agents, and legal counsel. The range of these business endeavors shows projects as grand as stage sets and murals, as well as other undertakings more broadly targeted as profitable: mass production arrangements for fabrics, wallpaper, greeting cards, posters, and advertising campaigns. Ms. Bair’s intention is to underscore Steinberg’s popularity as well as his income, and she notes, “By the late ’50s he was on the verge of becoming a very wealthy man who had the luxury of doing exactly what he wanted to do.”

There were books of artworks too, some requested by publishers and others self-initiated. Ms. Bair uses this aspect of Steinberg’s career to portray him as deeply philosophical and sensitive to every nuance of interpretation as he pondered various combinations of drawings produced over decades. Creating work that could transcend a specific time or situation and achieve universality pleased him enormously. Book and catalog essays often came from literary figures, including Harold Rosenberg, John Updike, Arthur Danto, John Hollander, Italo Calvino, Michel Butor, and Roland Barthes. Many writers were also friends, to some degree. At times Ms. Bair’s efforts to show intellectual rapport between Steinberg and renowned men and women of letters raise more questions than they satisfy, for the text can seem like inventories of dinner party attendees.

A tendency to be overly generous in listing celebrity names is one of the problems with this extensively detailed book. Another is the way the author gives the impression that she has not formed an attitude toward her subject. She seems in awe of Steinberg’s talent, praising every small and large accomplishment and suggesting that he be defined as a social historian and cultural anthropologist, yet at the same time she shapes and selects documentation for his emotional thoughts and actions as if inviting the reader to form negative judgments. In still another vein, she seems to offer childhood experiences and inherited angst as excuses for behavioral extremes. In offering citations, she references interviews and the vast breadth of the Steinberg archival material, especially the correspondence. Letters addressed to Buzzi confide most every private passion over more than 60 years, for example.

The book’s two paths, the career and the personal relationships, both have the ingredients to propel the narrative with much momentum, yet they also produce a disharmony that can feel irritating. Discussions about the art achievements occasionally seem recitative in Ms. Bair’s handling, while the exposure of Steinberg’s psyche might seem overwhelming in its thoroughness. Yet both avenues are compelling, and certainly they help the book to more than adequately deliver the complexity that characterized Steinberg’s life.

Phyllis Braff is an art critic, curator, and former museum administrator who lives in East Hampton.