Long Island Books: Paths to Freedom

“The Underground

Railroad on Long Island”

Kathleen G. Velsor

History Press, $19.99

In recent years, the Underground Railroad has received extensive attention. The National Park Service’s Network to Freedom and the Underground Railroad Heritage Trail of the New York State Office of Parks promote understanding of the movement. On Long Island, Kathleen G. Velsor, a professor at the State University at Old Westbury, has devoted decades to researching local connections to the Underground Railroad, focusing on the activities of members of the Religious Society of Friends (popularly known as Quakers). She contributed chapters to books on the subject published by the Queens Historical Society in 1999 and 2006 and wrote a young-adult historical novel in 2005.

Now she has presented the results of her years of research in a 144-page paperback that has more than 55 illustrations, including vintage and recent photographs of homes and meetinghouses, period engravings, and maps.

The Underground Railroad refers to the process by which enslaved people in the South escaped northward in the years before the Civil War, assisted by abolitionists and other sympathizers. Since aiding slave fugitives was illegal, documentation of Railroad activities is sparse and often limited to oral accounts passed down in families and churches.

Many today do not realize that slavery ever existed in New York. On Long Island in 1771, 17 percent of the population was black and virtually all were enslaved. By 1790, slaves were 32 percent of the population in Kings County (today’s Brooklyn), 14 percent in Queens (including present-day Nassau County), and 7 percent in Suffolk County and also in the Town of East Hampton. Suffolk was the only county in the state where free blacks outnumbered slaves. In 1799 New York adopted a gradual manumission law. Those born after July 4, 1799, would be free, females at age 25 and males at 28. Later legislation ended all slavery in New York in 1827.

In her recent book, “The Underground Railroad on Long Island: Friends in Freedom,” Ms. Velsor focuses on a number of Quaker families, including the Hickses, Jacksons, Motts, and Posts. The Quakers have kept excellent genealogical records, but providing names of so many relatives and their relationships risks bogging down readers.

Elias Hicks (1748-1830) is featured for his antislavery stance. He helped convince fellow Quakers to manumit and educate their slaves. In 1794 he was the “driving force” in organizing the Charity Society on Long Island, which opened three schools for blacks before public schools existed.

Ms. Velsor also identifies several Quaker homes in Jericho connected with the Underground Railroad. According to a 1939 account, the Ketchams “often took in runaways.” The attic of the Jackson-Malcolm house apparently was used as a school for fugitives from the South. A linen closet on the second floor of the home of Valentine Hicks hid a staircase to the attic where escapees may have stayed, according to family stories. Largely as a result of Ms. Velsor’s research, the Town of Oyster Bay recently landmarked this site, better known today as the Maine Maid Inn.

Upstate, in Rochester, Amy and Isaac Post were active in antislavery activities. Correspondence from their Westbury friends and relatives offers some clues to fugitive activities on Long Island. In Old Westbury, the Old Place home of the Hicks family on Post Road had hiding places recorded in family accounts. Other locations Ms. Velsor identifies as associated with the Underground Railroad include the Jerusalem “Brush” area in today’s Wantagh, the Townsend family’s Mill Hill house in Oyster Bay, the Roslyn gristmill, and the Mott homestead in Sands Point.

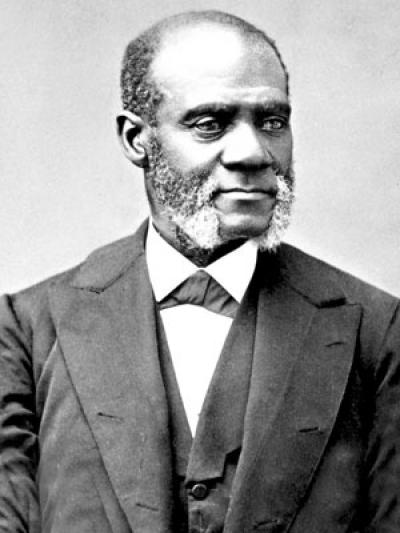

Henry Highland Garnet’s early years in Smithtown are familiar to historians, but Ms. Velsor has expanded the material on the subject by providing details of his family’s escape from New Market, Md., in 1824. Less well known is the experience of the 27 people who, aided by North Carolina Quakers, found temporary refuge in 1835 with members of the Jericho and Bethpage Meetings.

In her enthusiasm for the subject, Ms. Velsor includes information somewhat tangential to Long Island and the Underground Railroad. Some examples are the history of Quakers in New York in the 1600s, information on slavery in New York City, and the Underground Railroad in Westchester and Dutchess Counties. Quakers were not the only Long Islanders to be involved in antislavery activities and the Underground Railroad. Black churches, including St. David’s A.M.E. Zion Church in Sag Harbor’s Eastville, may also have aided escaped slaves, although Ms. Velsor does not mention them.

At times, Ms. Velsor uses the first person, explaining how she conducted her research through interviews and travels. This personalization enhances the reader’s interest. Unfortunately, a number of errors have crept into the text, such as incorrect dates and quotations, and the misspelling of names.

Ms. Velsor often uses language such as “is believed to,” “could have been,” or “it is reasonable to believe” without citing definitive evidence. Most of the few written accounts (based on oral traditions in families) were not set down until more than a hundred years after the events occurred. Ms. Velsor concludes that “the story of how the Quakers on Long Island helped enslaved people to freedom should no longer be subject to speculation.” However, this writer doubts that Long Island’s role in the Underground Railroad was as extensive as Ms. Velsor claims. It would have been a detour for most northern escapees.

I commend Ms. Velsor for her tenacious research over many years and for developing relevant educational materials. She has assembled a great deal of related information, and her book joins the few others on Long Island’s black history, specifically Grania Marcus’s “Discovering the African-American Experience in Suffolk County, 1620-1860” (second edition, 1995) and Lynda R. Day’s “Making a Way to Freedom: A History of African-Americans on Long Island” (1997).

“American Antislavery Writings”

Edited by James G. Basker

Library of America, $40

James Basker’s anthology of edited readings, “American Antislavery Writings,” provides in its 963 pages more than 216 selections by 158 writers, plus 22 illustrations. Introductions to each selection and a useful chronology provide context, and 48 pages of notes make this an exemplary reference work.

Seven of the eight earliest writings included, spanning the years 1688 and 1759, are by Quakers, most from Philadelphia and environs. Some selections are by statesmen (including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and of course Abraham Lincoln), poets and writers (e.g., Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow), abolitionists (William Lloyd Garrison, Charles Sumner, and John Brown), and former slaves (Frederick Douglass, Solomon Northrup, and Harriet Jacobs), to mention just a few. Nearly one-fourth of the writers were African-Americans, and one-fourth were women.

A few of the authors have connections to Long Island. Jupiter Hammon, who was enslaved by the Lloyd family, is represented by his 1782 poem “Kind Master and the Dutiful Servant.” The editor notes his careful “resistance to the master on theological grounds, not daring, as a slave, to utter a claim based on civil or natural rights.” (Unfortunately, Queens Village is wrongly located as “now part of New York City,” rather than on Lloyd Neck, north of Huntington.) Also included is a 1774 letter by the better-known black poet Phillis Wheatley to Samson Occom, the Mohegan minister who was ordained in East Hampton in 1759.

As a U.S. senator, Rufus King spoke against the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819. King’s country estate in Jamaica, Queens, is now a historic house museum (King Manor). The argument by former President John Quincy Adams before the Supreme Court in 1841 in the Amistad case is quoted, defending the Africans captured off Montauk.

Another author in the anthology, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was born in Litchfield, Conn., a year after her father, Lyman Beecher, left his 12-year ministry at the East Hampton Presbyterian Church in 1810. Her 1842 novel, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” was the “most celebrated” of American antislavery writing.

Long Island’s Walt Whitman, whose birthplace in Huntington Station is now a state historic site, is represented by his 1860 poem “Mannahatta,” celebrating “The free city! no slaves! no owners of slaves!” William Cullen Bryant, whose country home in Roslyn Harbor (Cedarmere) is owned and under restoration by Nassau County, has two poems, “The African Chief” and “The Death of Lincoln.”

Henry Highland Garnet appears in both books, having spent two of his teenage years in Smithtown as a fugitive. After he became a famous minister and abolitionist, he was the first African-American to address the U.S. Congress, one of two of his speeches reprinted in the anthology.

Although no Long Island Quakers are included in “Antislavery Writings,” they were in the forefront of those who early freed their slaves and educated free blacks. Quakers acted on their beliefs by their participation in the Underground Railroad. Ms. Velsor’s and Mr. Basker’s books both provide extensive information on the efforts to end slavery. They are welcome additions to local history and the literature of antislavery.

Natalie A. Naylor is a retired Hofstra University history professor and author of “Women in Long Island’s Past: A History of Eminent Ladies and Everyday Lives,” published last year. She lives in Uniondale.