Long Island Books: Poetry Isn’t Dead, It’s Just Playing Dead

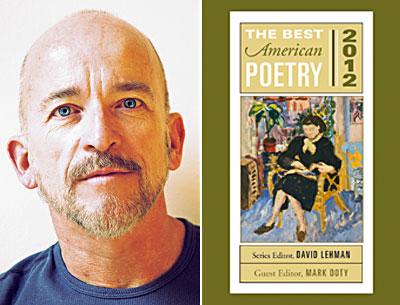

“The Best American

Poetry 2012”

Edited by Mark Doty

Scribner Poetry, $16

“Rain falls on the Western world, / the coldest spring in living memory everywhere,” begins Frederick Seidel’s “Rain,” one of 75 poems chosen by Mark Doty for the 25th volume of “The Best American Poetry 2012.” Mr. Seidel’s words could serve as an epigraph to this twilit anthology whose poems tend to exhibit an intense interest in death and the paranormal, casting shadows over the warm weather of poetic play with (in W.H. Auden’s words) the “problematic, the painful, the disorderly, the ugly.” And although much of the stormy weather in “The Best American Poetry 2012” is leavened by humor, the poets rarely flash the kind of conciliatory smile we expect from our local weatherman.

No consolation, for example, is found in Lynne Sharon Schwartz’s disturbingly funny “The Afterlife,” in which the speaker dreams of encountering her mother in heaven only to be rebuffed. “There are no mothers here,” says her dream-mother, “just separate souls.”

And in Paisley Rekdal’s long poem that braids the French Revolution, cancer, and waxworks, Ms. Rekdal, commenting on the wax figures in Madame Tussauds, notes: “there is a death / even for the deathless, objects / that depend on reputation to survive . . .”

Even Billy Collins, the country’s best-known comic bard, is here represented by “Delivery,” a short poem in which he imagines the news of his death being borne by “a little wooden truck / or a child’s drawing of a truck . . . and of course puffs of white smoke.”

To be fair, Mr. Doty, a resident of Springs and an award-winning poet himself, has done an admirable job of assembling poems that employ a variety of forms (ghazals, sonnets, prose poems) and registers (from the irate to the tender). Like previous guest editors of the series, he includes well-known poets (Mary Oliver, Mark Strand) and emerging poets (Eduardo C. Corral, Jenny Johnson). And there are plenty of poems in the book that deviate from dirge, glimmers of pure fun, such as the riotous opening of Jennifer Chang’s “Dorothy Wordsworth”: “The daffodils can go fuck themselves . . . I, too, have a big messy head.” Or Mary Ruefle’s “Middle School,” in which the students of a school named after the famously solitary Italian poet Cesare Pavese “all became janitors, / sitting in basements next to boilers / reading cheap books of Italian poetry, / and never sweep a thing. / Yet the world runs fine.”

Other poets in “The Best American Poetry 2012” appear less comfortable tending the boiler and reciting Auden’s maxim “poetry makes nothing happen.” The Bay Area poet Brenda Hillman’s prose poem, “Moaning Action at the Gas Pump,” is more manifesto than poem, exhorting readers to “start a behavior of moaning outdoors when pumping gas.” Ms. Hillman’s outrage may not make for the “best” poetry in the classical sense (i.e., it doesn’t sing and leaves little to the imagination), but our gas-guzzling culture, it suggests, neither deserves nor needs that kind of music. To survive, she writes, we must “shred the song.”

For those seeking chords of rapture, there is the hypnotic anaphora of Terrance Hayes’s “The Rose Has Teeth”:

I was trying to play the twelve-bar blues with two bars.

I was trying to fill the room with a shocked and awkward color,

I was trying to limber your shuffle, the muscle wired to muscle.

And Fady Joudah’s elliptical “Tenor,” where “each boy sits next / to his absence and holds him / in the space between two palms / pressed to his face — / this world this hospice.”

Less conventional is the beauty Heather Christle resuscitates from the deadening lingo of computer programming. Ms. Christle, a young poet with a voice that’s difficult to shake, generates an eerily sad music through the repetitious language of the computer program BASIC:

This program is designed to make people cry

and step away when they are finished.

In one variation the line moves diagonally

up and in another diagonally down.

This makes people cry differently,

diagonally. A whole room of people . . .

So many American poets are writing in so many styles nowadays that Mr. Doty’s task — and that of the series editor, David Lehman — seems highly fraught. In the past, “The Best American Poetry” series has been much maligned and contested for privileging certain kinds of poems and ignoring others. While Mr. Doty has succeeded in being a relatively democratic guest editor, one gets the feeling that this year the “Seventy-Five Poems Mark Likes” — as Mr. Doty modestly suggests renaming the volume — are unusually obsessed with mortality. Most poems, of course, are. These poems depart from traditional ruminations on the afterlife in their humble, often humorous tone and in their preoccupation not with individual mortality, but with the mortality of the species, a word that rhymes — in the ears of contemporary versifiers — with the word speech.

Perhaps, then, it’s fitting to close on Steven Orlen’s gentle, plain-spoken “Where Do We Go After We Die.” Mr. Orlen, who taught at the University of Arizona for over 30 years, died before his poem appeared in print. In a note on the poem, Tony Hoagland, Mr. Orlen’s literary executor and former student, writes, “The poem is about stories as much as death: its final lines rather magically depict the end of all narratives, and the onset of speechlessness.” Here are those lines:

The bartender is drying the last of the glasses,

Stories slide under the chairs into the shadows,

Speech reverts to its ancient, parabolic self — Yea,

Though I walk through the valley —

And actions lose their agency — It came to pass —

The things of the world become scarce,

And what’s left spreads its wings

And flies around among them, like bats at dusk.

Will Schutt, who lives in Wainscott, won the 2012 Yale Younger Poets Prize. His collection “Westerly” is due out in April from Yale University Press.