Long Island Books: Quiet Comfort, Rich Gossip

“The Southampton

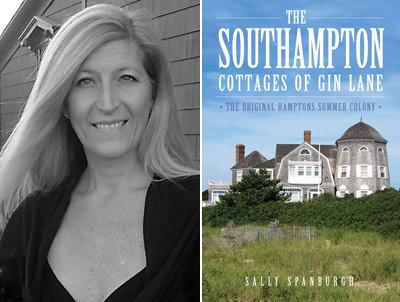

Cottages of Gin Lane”

Sally Spanburgh

History Press, $21.99

May King Van Rensselaer, in her quite brilliant book “The Social Ladder,” published in 1924, clearly states what the formula was behind the thoughts of those 19th-century colonists who planted their banknotes of conquest throughout the South Fork of Long Island.

She writes: “East Hampton, a neighboring village, also clings to the conservative fashions and manners of bygone days. Though the summer colony was not originally a creation of the old Society, many of the latter have since built homes in or near the town. They, like their neighbors of Southampton, rank comfort before splendor and cherish a Society based on a community of intellectual tastes rather than a feverish craving for display and excitement. Of all the social colonies that New York Society has planted in the great length and narrow breadth of Long Island these two alone still cling to the standards that the rest of present Society ignores.”

Southampton and East Hampton were about rural pleasures and restful escapes from society. There was an anti-Newport mentality — a summer away from the pretensions and demands of social position and the required social expectations.

East Hampton’s summer colonists began arriving in the mid-1840s, when the Long Island Rail Road went from Brooklyn as far east as Medford Station (Patchogue), where a stage was ready to take customers to as far as Montauk Point. It was the boarding house era. The Morgan Dix family spent several summers at Mr. Candy’s Boarding House in Georgica from 1845 until 1847. Morgan Dix’s diary recorded that they went out to see the Montauk Light. The family stopped at First House, where they were shocked at being charged $1 for milk and cookies. At the Lighthouse they were treated to a meal that was prepared by native people who lived in wigwams and frame shakes on the fringe of the keeper’s house.

The first summer cottage in East Hampton was likely that of the Rev. Stephen L. Mershon, who built Sea Side Cottage about 1871. Quickly a cluster of summer houses were established along Ocean and Cottage Avenues. These houses tended to be built in styles then in vogue, tending toward the Victorian picturesque. Second Empire, Italianate, Stick Style, and bits of the Gothic Revival seemed to be the most popular flights of summer house fancy.

Southampton’s first summer cottage was built by Leon Depeyre De Bost about 1875, on South Main Street following rows of the village’s whaling captains’ prim old Greek Revival homes. But the next group of cottages seemed to take on a more antique bent. In 1876, America had a birthday party in Philadelphia that celebrated American history and our new enthusiasm for the industrial arts. This Centennial Exhibition was on the scale of England’s inventive earlier World’s Fair. States created exhibit halls that copied their most famous historic buildings. Colonial culture became more than just a fad; indeed, architecture throughout the country was influenced by old Cape Cod cottages, shingle-clad saltboxes, New England Georgian mansions, Virginia plantations, and Philadelphia’s Independence Hall.

Coupled with an isolationist myth, the Hamptons (I’m sure the term is a bit older than the first reference I have found, but “the Hamptons” does appear in the Aug. 9, 1876, edition of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle) do generate a surprisingly forthright style of unadorned architecture that is at once romantic, practical, and colonial. It follows the code of quiet culture that Mrs. Van Rensselaer called “comfort before splendor.”

A new book by Sally Spanburgh, a Southampton preservationist, “The Southampton Cottages of Gin Lane,” is a wonderful way to discover the distinct look of our old South Fork summer cottages that follow the shore (south of Montauk Highway) from Quogue to Amagansett. Ms. Spanburgh has formed an excellent reading route by putting together a well-illustrated walking-tour booklet that brims with social chitchat and some surprising revelations.

Southampton’s Gin Lane isn’t really a microcosm of the development of our individual summer communities, but it follows a pattern that is not unique, and its late-19th and early-20th-century summer homes are representative of what is an East End aesthetic. It is certainly not what present-day magazine writers love to call the “Hamptons Style.” Sadly, today this term signifies a bland concoction of ill-conceived and clumsily proportioned, overfed Shingle Style want-to-bes that have little to do with the Hamptons and rather less to do with style.

What we first learn from Ms. Spanburgh is about Southampton’s summer colonists and how homogeneous they all were. Friends of friends, doctors of patients, patients of doctors, bankers and clients — everyone seemed to know one another, and at times rather intimately. Ms. Spanburgh describes them as “not the most affluent among the social elite but just below them, of ample means and good reputation, with ancestry that usually extended deep into the formation of the state of New York, and while always having their endeavors chronicled in the society pages of numerous publications, they were not highlighted by a hypothetical or literal spotlight. They consisted of doctors, lawyers and judges, stockbrokers, real estate brokers, bankers, publishers and merchants. . . .”

And clannish they were. They picked up good-size lots both for themselves and for investment. They bought up land that had been in families since the 1600s. Some of it was farmland that was too close to the ocean or grazed or farmed-out. The new colonists often would build a cottage for rent and one for their family. Or they would purchase several lots and hold them until the value increased or they looked for a fellow club member or family from a nearby church pew who could be interested in building in Southampton.

Land values were low after the Civil War, but once the first city investors arrived, in the 1870s, those $25 acres moved up to $200 each. Dr. T. Gaillard Thomas (a founder of the Southampton summer colony) bought 13 acres on Gin Lane for $2,743.75 in 1877. By 1887, Mr. William P. Douglas paid $12,650.00 for five and a half acres at 212 Gin Lane. A handsome increase even in a hot real estate market.

Once these intrepid 19th-century colonists had acquired their seaside land, it was time to construct a cottage that might bear an appropriately riparian name like Dune Eden, Over Dune, Sandymount, or Seaward. Ms. Spanburgh relies on many wonderful period postcards from the extensive holdings of Eric Woodward, a Southampton architect, to illustrate the Gin Lane summer houses. The pictures fill in for her rudimentary descriptions.

Though there are some splendid houses, such as Over Look and Wooldon Manor, the majority of the cottages are excellent examples of colonial revival and simple Shingle Style that need little use of adjectives, as they were always intended to leave the dramatics to their surroundings. Indeed, it is refreshing to sample such understated and familiar architecture.

These structures are not about ego, they are about friends and family filling bedrooms and playing in the surf. They are wooden framed and covered with wooden siding. They use gambrel gables like Southampton’s mid-18th-century Pelletreau Gold Shop and shingles like the 1660s Halsey House. It is vernacular building for modern times. Each house is a theme in variations. Longer, taller, boxy, or towered, they all use the same elements to achieve slightly different effects, but they are mostly members of the same family.

What is different about each of these Gin Lane cottages is who built them and lived within their walls. Here Ms. Spanburgh turns herself into a social historian (and perchance a gossip) as she vigorously searches through records and old newspaper clippings to document the lives of each of these Gin Lane residents. It is all rather rich, this 19th-century dishing. It’s really all about the cottagers. Who died young? Who went to jail? Who retired early? Who was sleeping with what neighbor? It may be old news, but it is decidedly vintage wine. The cast of characters is rich.

Windbreak was the summer residence of Mr. and Mrs. Josiah Copley Thaw. Mr. Thaw’s brother was Harry K. Thaw, “who shot and killed the prominent architect, Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White, in 1906 because of White’s relationship with his wife. . . .” After being acquitted, Harry often stayed at his brother’s Gin Lane estate, “but was kept on the ocean side of the house.”

Each house holds several delicious secrets and loads of name-dropping, for instance William K. Vanderbilt, Chuck Scarborough, J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, Dominick Dunne, Gary Cooper, and Chester Dale. This book makes architectural history fun. I suggest you buy the book and read it through before you descend on Gin Lane to start your self-guided tour.

I’m sorry to say that the lane is named after the pen where stray cattle were impounded during the 17th century. Gin Lane was not named for either gin and tonics or rum-running. But I would suggest getting a vodka and tonic at Little Red (hiding at the end of Job’s Lane) for the long trip home.

As to why the author subtitled her book “The Original Hamptons Summer Colony,” I will never know. Southampton has a hard enough time trying to substantiate that it is “the first English settlement in New York State” no less now seeking to be the “original summer colony.” Oh well, I’ll blame it on the publisher. Now where did I put my drink?

Sally Spanburgh, the program coordinator at the Bridgehampton Historical Society, lives in Southampton.

Richard Barons is the executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society. He lives in Springs.

Spanburgh Speaks

Sally Spanburgh will talk about her new book, “The Southampton Cottages of Gin Lane,” on Saturday at 5 p.m. at BookHampton in Southampton. Ms. Spanburgh is the chairwoman of the Landmarks and Historic Districts Board of Southampton Town. She writes about architecture and preservation issues at shvillagereview.blogspot.com.