Long Island Books: Really Top Chef

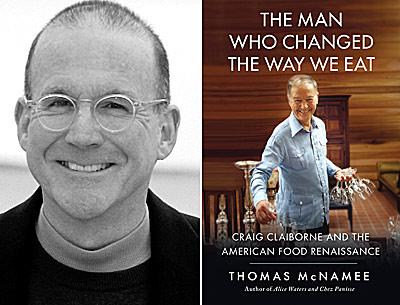

“The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat”

Thomas McNamee

Free Press, $27

When Craig Claiborne put his East Hampton house up for sale in 1988, the real estate agent included a long list of professional restaurant equipment in the “once-in-a-lifetime kitchen.” Apart from the many food columns, restaurant reviews, and best-selling cookbooks that made Claiborne’s reputation, the kitchen was about all he had left to show for his decades as food editor of The New York Times. It was largely paid for by The Times, proof of his success and his value, and it was where all those memorable meals were prepared by star chefs and consumed by notable guests.

For an asking price of $885,000, the atypical house on Clamshell Avenue facing Hand’s Creek was built to Claiborne’s plans in 1979. The kitchen had a stainless-steel Chinese roast pork oven, Salamander broiler, Simac “Gelatio” ice cream maker, Traulsen refrigeration, and 500-bottle wine closet. It was a kitchen wagging a house. Even by today’s measure, the space anchored by a 10-foot marble work island under a skylight would make Mario Batali wet his “Fanta pants” with excitement.

Claiborne had just definitively retired from The Times in 1988 when he tried unsuccessfully to sell the house. The food newsletter he once produced with the late Pierre Franey, his longtime Times colleague and East Hampton neighbor, had failed. The food world already had started to change around him. He needed to reinvent himself. Instead, as we see in “The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat” by Thomas McNamee, he continued a sad decline.

Reading this first comprehensive account of Claiborne’s life to appear since his death in 2000, it seems that he’s been given a somewhat ambiguous legacy 50 years after publishing his first column for The Times. In a world that has become so obsessed with food and dining, why did it take so long for someone to tell the story of someone so influential in what Mr. McNamee calls the “American food renaissance”? Why was Mr. McNamee, with only one other book in this genre to his credit — about Alice Waters and Chez Panisse — the one to write it?

No one doubts the extraordinary degree to which Claiborne changed what and how we eat today. Mr. McNamee accurately points out that it helped him to have the power of The Times behind him. Still, Claiborne set his own high standards that — at least before today’s food blogging free-for-all — were previously unimaginable. It’s difficult to measure his full contribution, not just to diners but to the food and hospitality trade.

Does it say as much about Claiborne’s contribution as it does about how his public, peers, and subjects ultimately perceived him that only now do we have a (sort of) definitive book about him? Has the rush to celebrity chef status and all its TV trappings reached such intensity that it has diminished Claiborne’s legacy so quickly? Or, as Mr. McNamee’s research attests, after years of not too successfully hiding his condescension is Claiborne seated in the restaurant equivalent of Siberia?

Perhaps that’s why Henri Soulé and his Le Pavillon restaurant in New York City (and brief summer outpost at the Hedges in East Hampton) were Claiborne’s ideals for fine French dining. Mr. McNamee shows us that Soulé was as much a dominant influence on Claiborne as his early studies at the Ecole Hoteliere de la Société Suisse des Hoteliers in Lausanne, Switzerland. Claiborne saw Soulé as the real thing, an imperious bearer of standards for classic French cuisine in a room governed by impeccable service — if not snobbism. In Soulé, Claiborne may unwittingly have come across the monster he was to help create in today’s egomaniacal TV celebrity chefs.

So what sort of monster has Claiborne created 50 years on? Take Scott Conan, the recent subject of a “Power Dressing” column in The Financial Times. Conan is 41, a U.S. chef, television personality, and cookbook author with six restaurants across this country and Canada. He’s been host of “24-hour Restaurant Battle” on the Food Network and is a judge on “Chopped.” Describing his shirt, Conan the power dresser informs us: “This is a light blue cotton, and woven inside the twill-like fabric is a darker blue. All my clothes are made to measure. I’m not just in the restaurant business; they’re quality restaurants so the shirt is representative.”

We can only imagine what Craig would say if he were around to read this sort of thing. Perhaps, “I’ll have what he’s wearing.”

Of all the people who could have written this book, why Mr. McNamee? To answer that you’d have to ask a long list of people who might have more deeply captured the era and the man. Gael Greene, for one, could have given us more zest and feel for her subject. Maybe there just wasn’t all that much material in the end. Were there too many falling-outs for anyone that close to him to want to put it all back together again? As informative as “The Man Who Changed the Way We Eat” can be, someday someone should delve more deeply into the social context that is the real payoff in what Claiborne accomplished for people and how they eat.

For now, Mr. McNamee gives us an accurate chronological account of a life and the people who were close to it before Claiborne’s darkness alienated them. He was frustrated in love and in not being able to live freely gay for much of his life. He drank a lot, and he largely ignored his deteriorating health later on.

In contrast to his subject’s élan, Mr. McNamee’s style is clunky and colloquial at times. There are stretches when he marshals so much information that the maddening signature of Zagat’s guide reviews comes to mind: Some readers will enjoy the accounts of feuding chefs, others will cringe at the attempts to put Claiborne’s sexuality into context.

In more than a few places Mr. McNamee’s references to food and cooking can seem more researched than knowledgeable. Other sections read as though he spent too much time in Claiborne’s archives rather than talking to people about him. We loved what Claiborne had to teach us, but everyone agreed that his writing mostly had the fluidity of a starched white napkin draped over a waiter’s forearm.

The book’s notes, credits, and index will be a helpful resource for those in the younger “Top Chef” generation who may just now be discovering Claiborne. Some of the detail seems included for the sake of proving that the research is ironclad. For those of us in East Hampton, it’s nice to know that Jacques Franey’s birthday is June 30 so we could wish him well when channeling his father, Pierre, at Domaine Franey Wines & Spirits on Pantigo Road. Among others, Mr. McNamee spoke extensively to Jacques’s sister, Diane, for the book.

Leaving no heirs, Claiborne left his estate to his great love, Jim Dinneen, and to the Culinary Institute of America, where a bookstore and scholarship fund bear his name. It was a fitting legacy from someone who long ago saw the value of such an institute in America — much the way Claiborne’s studies in Lausanne formed the approach to food and service he would keep forever.

While carefully describing the bitterness Claiborne never eluded, Mr. McNamee still makes sure Claiborne’s great kindness, generosity, and encouragement for others are given credit. Beyond helping Pierre Franey gain prominence, he backed Mimi Sheraton to become The Times restaurant critic, guided Marcella Hazan to produce one of the best Italian cookbooks ever written, and was the first to discover many other household names in the food business today.

As a side note, when I was a reporter for this newspaper in 1989 I got a call from Craig. He liked a piece I wrote about his Clamshell Avenue house being for sale. Would I organize the notes he’d been collecting for a book? We met at the house, I agreed, and I helped edit his last published book, “Elements of Etiquette: A Guide to Table Manners in an Imperfect World” (2001).

I don’t remember what he served at the first meal I had with Claiborne and Jim at the house, but I do recall the wine. It was a Simi Valley chardonnay I still buy today. Knowing about the famous $4,000 meal he and Pierre Franey shared in Paris in 1975 to stick it to American Express after winning a PBS auction, I had expected a bigger bottle, maybe a white Burgundy. No, the surprisingly crisp Californian was a sign of Craig’s egalitarian appreciation and respect for what was simply good.

Aside from its weak spots, Mr. McNamee’s book ultimately brings a complex and reserved man into accurate focus. We’re left with someone whose great achievements were overshadowed by loneliness and sadness. We wish he could have been a little less ahead of his time — for himself, and for us. In this era of “vibe dining” establishments and retina-exploding presentation, we could use a little more Claiborne.

Eric Kuhn is a former reporter and news editor for The Star. He has lived in Paris since 2000.

Thomas McNamee lives in San Francisco.