Long Island Books: Rumrunners’ Paradise

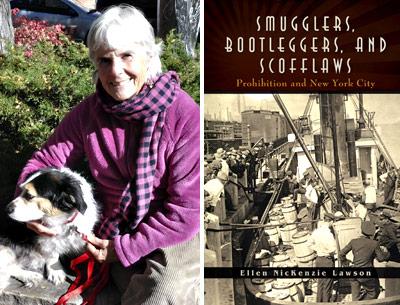

“Smugglers, Bootleggers, and Scofflaws”

Ellen NicKenzie Lawson

Excelsior Editions, $19.95

It was near midnight on Jan. 16, 1920, and at the Park Avenue Hotel in New York, waiters and patrons were dressed in all black and drank liquor from black glasses. Let Ellen NicKenzie Lawson take it from there: “At midnight the ballroom was darkened and a spotlight focused on two couples ceremoniously taking a black bottle from an open coffin in the center of the room, pouring out the last drops, and holding black handkerchiefs to their faces to wipe away tears.”

And so descended the Great Experiment, the 18th Amendment, Prohibition. As Ms. Lawson points out in her new book from Excelsior Editions of the SUNY Press, “Smugglers, Bootleggers, and Scofflaws,” historians are often “merely amused that Prohibition ever existed, embarrassed that the Amendment was ratified, appalled that it gave a boost to organized crime, and relieved that it was repealed.”

But what a rich trove for someone with a nose to find it. In neglected Coast Guard records in the National Archives, Ms. Lawson found not only documents and manifests but photos, including mug shots of captured gangsters and smugglers, maps, and nautical charts, among them one showing the locations of the supply ship Mazel Tov over the course of an entire year in what came to be known as Rum Row, southeast of Nantucket and Long Island, where liquor supply ships from Germany to Cuba stationed 12 miles offshore, outside the legal limit, waiting to run their lucrative errands to New York City.

Ah, Babylon-on-the-Hudson, Satan’s Seat, the biggest, unrepentantly wettest city in the nation, and its largest liquor market. For Ms. Lawson the city is the booze-happy center of gravity around which circles the Prohibition era’s most significant criminal activity, enterprising importers, creative rumrunners, gunsels, pirates, and dogged G-men.

And far out in that orbit, the rocky promontory that is Montauk came to be “a paradise for smugglers given its extensive coastal area and proximity to Rum Row.” Locals with intimate knowledge of the beaches and inlets were recruited to expedite the cargo to shore, where trucks with gangsters “riding shotgun” would haul it in nighttime convoys to New York.

Montauk saw a fair amount of gunplay — the first Coast Guard fatality of the Rum Wars was one result — and no end of watery chases. Vessels were rammed, went aground on Shagwong Reef, were torched, and one took 25 rounds of Coast Guard gunfire. A “fishing launch” seized off Culloden Point led an official to wonder, “What fish needs 800 horsepower to catch it?” Capt. John Hayes of Montauk was stopped at the helm of what had been a World War I American Red Cross yacht carrying 4,000 cases of whiskey.

In some instances, cases of liquor were tossed overboard to float for later pickup, or for retrieval from the bottom by hired divers. Thirsty locals could reap a bounty, too. After a Nova Scotia schooner went aground near Blackfish Rock, couples returning from a night out at a restaurant on Fort Pond Bay came upon hundreds of jettisoned bags of liquor bottles on the beach and soon found themselves fired upon by coast guardsmen. A group of men including Lennan Edwards and William Young returned at dawn with clam rakes, eel spears, and nets to retrieve the contraband liquor and were greeted by further volleys of bullets from Coast Guard vessels out of New London, leading the Suffolk County district attorney to lodge an official protest and complain to reporters.

It was, curiously, just one of a number of instances in which the coast guardsmen were the ones with the itchy trigger fingers, while the bootleggers were reluctant to return fire, employed, as the were, “to deliver liquor and not kill or die for it,” in Ms. Lawson’s words.

With the local police happy to be paid to look the other way, the liquor flowed. By the end of Prohibition, a syndicate run by T. Budd King and Emerson Tabor moved 10,000 cases a month between Montauk and Southampton, where scores of longshoremen were known to operate, with trucks stationed behind dunes and horse-drawn wagons waiting surfside.

Ms. Lawson places Prohibition within the tradition of the Progressive movement around the turn of the 20th century, which ended child labor, led to the regulation of food and drugs, and gave women the vote. The 18th Amendment was also the product of an America that was majority rural at the time of its passage and suspicious of cities. By the time of its repeal, at the end of 1933, however, the country had turned majority urban, with more immigrants and diversity and less of a belief in social engineering as the answer to the scourge of alcoholism.

The spirit of the scofflaw dates to the nation’s founding, of course, but what’s more, the “centrality of liquor” here, Ms. Lawson writes, can even be traced to the Pilgrims and their landing at Massachusetts because the shipboard supply of beer ran out.

And Manhattan, the center of those 14 years of alcohol-fueled gangland mischief? The resident American Indians had a name for it, once Europeans had started settling there: Manahactanienk, the “place of general inebriation.”

’Twas ever thus.

Ellen NicKenzie Lawson is the editor of “The Three Sarahs: Documents of Antebellum Black College Women.” She lives in Loveland, Colo.