Long Island Books: Sir Paul’s Not So Happy Hippie Decade

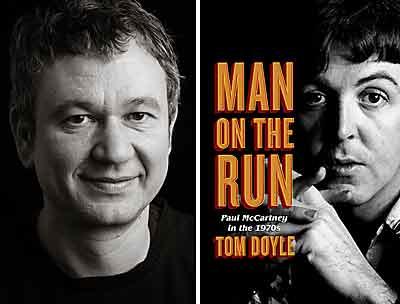

“Man on the Run”

Tom Doyle

Ballantine, $27

Rare is the artist whose cultural significance is such that a biography is devoted to a single decade in his or her life. But Paul McCartney, a popular-music phenomenon for a half-century and counting, has created a body of work deserving the same scrutiny as that of his former band, the Beatles.

At 72, Mr. McCartney, who has a house in Amagansett, continues to record and perform, the musician’s legendary work ethic undimmed by time. This week, he is in the midst of a world tour that, while partially postponed by illness earlier in the summer, is characterized by hours-long concerts and literally dozens of hit songs revered among all age groups and cultures.

As the title indicates, “Man on the Run: Paul McCartney in the 1970s” focuses on the artist’s first post-Beatles decade. In it, the veteran music journalist Tom Doyle digs deeply into Mr. McCartney’s life and career, doing fans a great service as he unearths details even the most obsessive among them likely did not know.

Mr. Doyle uses interviews with his subject as well as Ringo Starr, Yoko Ono, and former bandmates and others on the rock ’n’ roll scene to construct a thorough narrative of Mr. McCartney’s life and career in the 1970s, a period as prolific for the artist as the one that preceded it.

In Mr. Doyle’s telling, calamitous events serve as bookends for the decade. The first, of course, is the Beatles’ breakup, a years-in-the-making divorce that for a time left Mr. McCartney, then newly married to the American photographer Linda Eastman, shattered and secluded on a farm in remote Scotland, his sunny and cheerful public persona obscured by a deepening depression. “His often sleepless nights were spent shaking with anxiety,” Mr. Doyle writes, “while his days, which he was finding harder and harder to make it through, were characterized by heavy drinking and self-sedation with marijuana. He found himself chain-smoking his unfiltered, lung-blackening Senior Service cigarettes one after another after another.”

At the other end of the decade were two incidents: the first, a marijuana bust in January 1980, as Mr. McCartney and his band, Wings, landed in Tokyo for a tour of Japan. The artist was jailed for 10 days and the tour canceled, indirectly leading to the demise of Wings, which Mr. McCartney had first assembled in 1971. The other was John Lennon’s murder at the hands of a deranged fan in December 1980, a tragedy that rendered any true Beatles reunion impossible. “Always utterly thrown by death,” Mr. Doyle writes of Lennon’s murder, “McCartney was in a state of emotional paralysis.”

Between these bookends, Mr. Doyle writes, the shadow of Mr. McCartney’s former band, and particularly that of Lennon, his first and most significant artistic partner, loomed large. Millions yearned for a reunion of the Beatles, and, as revealed in “Man on the Run,” it was often a tantalizingly real possibility. While unlikely in the decade’s first years as the Beatles’ business affairs were slowly untangled in court and wounds of their acrimonious breakup gradually healed, Mr. Doyle documents occasional stirrings sprinkled throughout the decade, any of which might have blossomed into a full-fledged reunion.

Two other themes emerge through Mr. Doyle’s research. As the 1970s rose from the ashes of the previous, tumultuous decade, one in which the Beatles had delved deeply into mind-altering substances, Mr. McCartney in the new era is portrayed as a happy-go-lucky, whimsically stoned hippie. He documents the first “freewheeling, haphazard tour” undertaken by Mr. McCartney’s new band, which included his musically inexperienced spouse: “Everyone — musicians, roadies, kids, even dogs — was to pile into the vehicles and take off up the motorway, heading for university towns in search of somewhere to play.” Frequent marijuana busts and abundant music — sometimes self-indulgent and even silly but very often brilliant and enduring — further illustrate the theme.

The other is the inherent tension presented by Mr. McCartney’s twin desires to both be a member of a band, as he had with the Beatles, and simultaneously the unquestioned leader of said group. Surely, he had earned the right to direct the proceedings of his new creative vehicle. But, as it had among his collaborators in the Beatles, Mr. McCartney’s exacting direction rankled his new bandmates, often to a point of no return.

“Behind their happy hippie-family facade,” Mr. Doyle writes, “the discontent had been stewing in Wings for some time.” A quote from Denny Laine, the band’s longest-serving member, illustrates the point: “Let’s be honest — he wanted to be in a band in a sense. But he would still have the final call.” The lineup was ever shifting, no lead guitarist or drummer lasting more than a few years. While Mr. McCartney assembled many fine, hard-rocking iterations of Wings, the frequent turnover, and complaints of inadequate wages and the spartan living conditions on Mr. McCartney’s farm, hindered the effort to realize a “band” in the ideal sense — an egalitarian unit with common attitudes, goals, and, critically, respect.

Yet the record is clear. For all the dismissals of Mr. McCartney’s music as saccharine, nursery-rhyme fluff — “Muzak to my ears” was Lennon’s caustic assessment in an early post-Beatles song of his own — the artist recovered from the Beatles’ disbanding and produced another body of work that surpassed that of all but a handful of his contemporaries. Four decades on, the seemingly ageless Mr. McCartney has been performing a dozen or so of these post-Beatles hits, among a nearly 40-song set, on the aforementioned tour.

The decade, Mr. McCartney tells Mr. Doyle, represented achievement. “ ‘Achieving the impossible, really,’ he emphasized, before remembering the words of those critics who rejected the idea that he would ever create anything that could be held up against the golden light of the Beatles. ‘It had always been, “You can’t do that, that’s not gonna be possible.” I slightly believed that, and thought, Yeah, but I want to be in music, so I’m gonna have to do something, and this is my best shot.’ ”

“ ‘And it was a wacky thing,’ ” Mr. McCartney summarized. “ ‘But, come on, man, we were hippies.’ ”