Long Island Books: Suburban Madcap

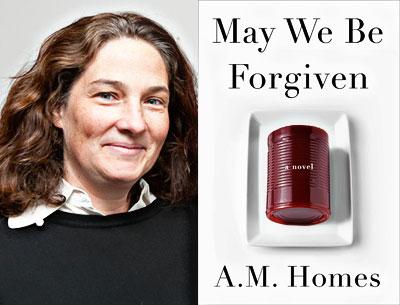

“May We Be Forgiven”

A.M. Homes

Viking, $27.95

A.M. Homes, author of “Music for Torching,” “The End of Alice,” “In a Country of Mothers,” and others, has a new one out. It has lots of characters and it covers lots of ground. It has ambition, authority, and plenty of laughs. It has keen observation of contemporary culture in big enormous buckets; it’s nothing if not right now. Finally, and not incidentally, Ms. Homes’s new one is on the longer side for contemporary literary fiction. You get in and stay in for a while. Big.

This is a category: the Big Book. Big Books are reviewed in The New York Times and placed on the front tables in bookstores. Big Books get attention, which is similar to buzz, but more literary. (If the Big Book doesn’t get quite enough attention, can it still be a Big Book? Does it go on the Big Book B list?) On the inside, a Big Book is like The Great American Novel — a reflection of the times in which it was written — only with less of a requirement for universality, the extra requirement of length, and the extra, extra requirement of investment. The writer invests her time, the publisher invests its power, the bookstore invests its shelf space, and the Big Book claims its corner with heft and authority.

It’s not clear what might happen to the Big Book if literature goes irrevocably digital, because it’s harder to be impressed by the length of a book when you can’t see it as a physical object. Yet another 21st-century conundrum for the publishing industry! But anyway, A.M. Homes takes herself seriously; her publisher takes her seriously. And her readers take her seriously, too, even as, or because, she cracks us up with a weird confection of absurdity and reality, a hilarity that starts on page one of “May We Be Forgiven” and ends at the end, on page 480.

The story of “May We Be Forgiven” takes place over the course of one year, Thanksgiving to Thanksgiving. It’s a blow-by-blow of the events in one man’s life, and there’s a lot involved. Betrayal, death, legal guardianship, sex in the suburbs, power of attorney. The protagonist of the book is Harold Silver, and it’s his book — his story, his year, his first-person narration, his transformation.

At the opening of the book, Harold is a Nixon scholar, married with no children, living in New York City and inhabiting a thin and disconnected emotional life. Meanwhile, Harold’s brother, George, is a television network executive, married with two adolescent children, living in the suburbs and playing out his role as angry, aggressive golden boy.

The book hits the ground wild and running: A car accident for which George is at fault kills two adults, orphaning a child. George is removed to the hospital. Harold is called in, stays with his sister-in-law by way of support, and the two begin an affair. When George emerges from the hospital and discovers the affair, he brutally and fatally attacks his wife with a bedside table lamp. All of this happens in the first 15 pages of the book. In the vacuum created by these events, Harold is left in charge of his brother’s life. Here is how Ms. Homes accomplishes this transfer of responsibility that gives way to the rest of the book:

In the lobby of the hospital, the lawyer asks me to take a seat. He places his enormous bag on the small table next to me and proceeds to unpack a series of documents. “Due to the physical and mental conditions of both Jane and George, you are now legal guardian of the two minor children, Ashley and Nathaniel. Further, you are temporary guardian and the medical proxy for George. With these roles comes a responsibility that is both fiduciary and moral. Do you feel able to accept that responsibility?” He looks at me — waiting.

“I do.”

Harold’s wife gets wind of his affair with his sister-in-law and divorces him summarily, setting the stage for a delve into Internet-arranged sexual escapades that take place during the day in the suburbs. These escapades lead to an actual, though totally nonconventional, relationship full of honesty and funny dialogue, which develops alongside and in counterpoint to another romance, disjointed and mysterious and also non-conventional.

Meanwhile, Harold adopts the child orphaned by the car accident that began the novel’s proceedings and takes in an elderly couple who began as incidental characters connected to the second nonconventional romance. Throughout, in the background that trades places with the foreground, Harold becomes increasingly bonded to Ashley and Nate, his niece and nephew, and increasingly tied to the life in the suburbs into which he’s stepped.

The plotline is madcap and absurdist — at one point Harold’s brother is taken to an “alternate prison setting” where he’s left with a group of other prisoners to survive in the wilderness; at another point, Harold is held prisoner in a suburban home by the children of a woman he’s arranged a “lunch” meeting with over the Internet. That kind of absurd.

In terms of plot, Ms. Homes replaces necessity with quantity: It is important in this book that many crazy things happen, but less important exactly what those crazy things are, as long as they provide opportunity to observe contemporary culture (e.g., hand sanitizer, ubiquitous medication, a party planner who believes she should “follow the aesthetic” of the writer Lynne Tillman).

Yet the dialogue in “May We Be Forgiven” is realistic and naturalistic, specific, pitch-perfect, and extremely adroit. Also, it’s hilarious. Although entertaining almost the whole way through, the novel is most engaging when the absurd and the realistic meet and fuse. This happens most touchingly through Harold’s growing love and sense of responsibility for his niece and nephew.

Along that line, a standout scene happens about a third of the way through the book: Harold is on the phone with his adolescent niece, who has called to talk with her mother, who at that point in the story is dead. The niece knows this, but she’s gotten her period for the first time and she’s desperate. “I tried to use the Tampax,” Ashley says, bursting into tears again. “I put it in the wrong hole.”

“You know how there are two holes down there?”

“I think so,” I say. “I put it in the wrong one.”

“How do you know?”

“It doesn’t feel right.”

“You put it in your tush?” I don’t know what else to call it — I don’t want to say “behind” because everything we’re talking about is behind. . . .

Harold successfully talks his niece through the safe removal of the tampon. The conversation is both absurd and realistic, funny and crazy and full of love and trust and just the madness of what it means to love and take responsibility for a child. Ashley hangs up the phone, and Homes/Harold says, “I am shaken, but, oddly, I feel like a rock star, like I am a NASA engineer having given the directions that saved the space lab from an uncertain end.”

The virtue in the length of “May We Be Forgiven” lies in the quasi “real time” experience of reading a long book in which the passage of time — that blow-by-blow — is an important factor. You’re in it, too. This is heightened by the absence of chapters or parts: The narrative unfolds in one long chunk, variegated only by line spaces to indicate transitions. These sections range from several pages to a single paragraph, and the arrangement is effective. It’s the sense of flow: You can stop and take a break, but it’s all one thing, and so is life.

It’s worth noting that in spite of the events upon which the book is based — the affair and murder — “May We Be Forgiven” is not mainly a story about sibling comparison or conflict, or as we say in the Mama business, “brother stuff.” So what, then, is this Big Book about? One little word, my friends: change.

Narrator/protagonist/hero Harold Silver begins lonely and disconnected and takes on a ragtag family cobbled together from the events of the novel. He goes from a stunted emotional life to a rich one. Ms. Homes plays with a certain expectation in literature that characters change, that this is what makes a story a story. Here, the transformation of Harold Silver is both absurd and realistic.

And what is the mechanism behind his change? He accepts absurdity as opportunity: He’s willing. That active, that refreshing: Harold Silver is willing to try. He doesn’t know what he’s doing but he’s willing to try to do it anyway. Absurd and real and big.

Evan Harris is the author of “The Art of Quitting.” She lives in East Hampton with her husband and two sons.

A.M. Homes has a house in East Hampton.