Long Island Books: Talkin’ Revolution

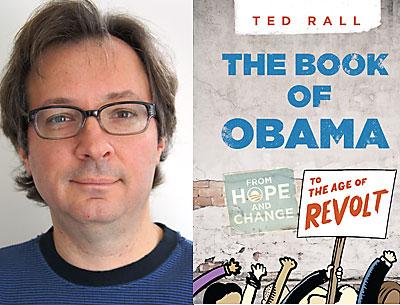

“The Book of Obama”

Ted Rall

Seven Stories, $14.95

The current state of the United States maddens Ted Rall, and in his most recent book, he seeks to enrage his readers. While the book will most likely anger many people, the ire it raises may not always be focused in the way Mr. Rall intends. The problems that Mr. Rall deftly elucidates — income inequality, political hypocrisy, crony capitalism — trouble me; in fact, they deeply trouble me, but, as I read “The Book of Obama: From Hope and Change to the Age of Revolt,” I also felt upset by the gaps in Mr. Rall’s logic.

Mr. Rall’s work is very important because the mass media, governed by commercial and political interests, ignore the decidedly unglamorous and morally disquieting stories of poverty, international human rights abuses, and corrupt business that Mr. Rall addresses. The flaws in his book are in no way a reason to ignore these very true and very important problems. But, to address these problems, we need to move beyond either/or logic; we need to reimagine the possibilities of nonviolence, and we need to always remember that the future involves all of us, not us versus them.

Let me first emphasize that Mr. Rall gets so very much right. For example, he is right when it comes to political hypocrisy and international affairs. Waging wars to oust some dictators based on their human rights records while courting other dictators with equally reprehensible human rights records is nothing new, but Mr. Rall makes us look at this anew when he contrasts U.S. relationships to Libya with U.S. relationships to Uzbekistan. We invaded Libya in 2011 with the purported intention of toppling Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi because of his dictatorial rule. In the same year, the U.S. lifted sanctions against Uzbekistan in order to cultivate a relationship with Islam Karimov, whose government had attracted the attention of Amnesty International for, among other atrocities, boiling dissidents alive.

Mr. Rall not only points out this hypocrisy, he also connects these international problems and the money we spend on war with national problems of debt and the lived experience of Americans who are suffering because our government hasabdicated responsibility for really protecting its citizens. He makes us see that the real threats to our security come not from foreign dictators but rather from the predations of capitalism, as practiced by Americans and by others. He is right.

I part from Mr. Rall when he directs much of the blame at President Obama and argues that we will not find viable solutions in our current political system. I believe President Obama has made some progress on a number of the problems he inherited. This is not enough for Mr. Rall. A crucial part of his argument is that incrementalism does not work, and he offers a witty cartoon to illustrate this. It imagines what would have ensued had Lincoln employed incrementalism: 4 percent fewer whippings rather than the abolition of slavery.

Mr. Rall’s cartoons are like funhouse mirrors that force us to see the hypocrisy of much common sense. While I agree that incrementalism alone will not work, Mr. Rall misleads by offering a false choice between incrementalism and revolution. This false choice, relying on either/or logic, conceals other options, such as pursuing incremental change within the system and also engaging in other work to enact change.

Here is what I mean. We can vote and we should vote because there are real differences between the candidates. I believe that President Obama has done a better job than John McCain would have and that today, President Obama offers a different vision of the future and different policies than those Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan propose. Because these differences will have concrete consequences on our lives, I will vote for Barack Obama.

In addition to voting, we can work outside the system in a range of ways. Mr. Rall’s outside-the-system solutions are more interesting, if less precise, than his exhaustive and exhausting critique of President Obama. In some ways, he addresses the final chapter of this book to the leaders of the Occupy movement, urging them to make greater efforts to find common ground with the many disenfranchised Americans who have been and continue to be hurt by business as usual. Yet, he also advocates violence as a necessary component of change, a position that would not help the Occupy movement find common ground with mainstream America.

Last autumn, harvest time, I kept expecting the Occupy protesters in New York to hack through the concrete sidewalks of downtown Manhattan and start planting vegetable gardens. That is how the revolution began in Starhawk’s 1993 novel “The Fifth Sacred Thing,” a work that helps me understand the limits of Mr. Rall’s argument for violent interventions. Creating gardens out of concrete is no longer a utopian dream, but rather part of a global movement of people finding power in their ability to feed themselves and their communities.

In addition, some people are establishing time banks that encourage barter rather than reliance on the dominant economy. Transition towns, so named because they are actively working to make the transition to more sustainable communities by reducing dependence on fossil fuels, offer a model for enacting change on many levels. We can take steps that will make our lives better in material, aesthetic ways, steps that will improve our communities and pave the way for a more equitable and environmentally sound future, and we can also vote, thereby working toward a better world within the system and beyond it.

Mr. Rall reminds us of how much work needs to be done; we need to engage in this work in many ways.

Stephanie Wade teaches writing at Unity College in Maine and spends summers in East Hampton.

Ted Rall has a house in East Hampton.