Long Island Books: Telling Truths

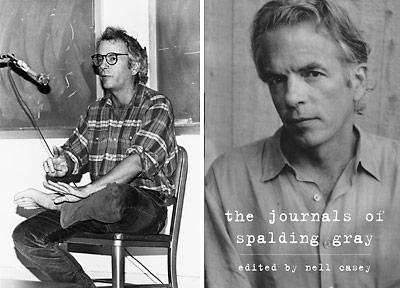

“The Journals of Spalding Gray”

Edited by Nell Casey

Alfred A. Knopf, $28.95

Creatives have the propensity to see life in quotations. However Job-like their experience, the proclivity and ability to turn it into art is ultimately a redeeming factor. Naturally the inclination to treat all of experience as a palette can also have a distancing effect. Nothing is ever taken at face value or enjoyed for what it is.

Early on in his journals, Spalding Gray says, “Would you take one complete and happy pump me up to the sky swing on that swing — or would you rather have a life long photograph memory — correct artistic interpretation of the swing — goddamn it I’d take the art.”

Nell Casey, who edited “The Journals of Spalding Gray,” points to a tradition of “confessional storytelling” that runs from Saint Augustine through Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Sylvia Plath, and Richard Pryor. Monologues like “Swimming to Cambodia” and “Gray’s Anatomy” established Gray as a significant part of that tradition.

Intimacy is of course the lingua franca of this kind of monologue, and as with the patient in therapy the monologuist is creating a narrative. The difference of course is that the primary motivation of the monologuist is to entertain and perform, while that of the patient is to get well. However, the willing suspension of disbelief that Gray was able to create, through his candid descriptions of sex and other elements of his personal life, may explain the shock and betrayal many fans felt when they learned he had thrown himself off a Staten Island ferry in 2004.

In her introduction, Ms. Casey points out that “The feeling of public devastation that rose up after his death came in no small part from the fact that the decision to end his life — and the act itself — were so private. Gray, by virtue of the ongoing autobiography of his monologues, had promised to tell his audience everything.” Yet, “Gray could not reveal everything, not only because he knew the best stories were lively distillations, but also out of the fear that too bold a truth might alienate his followers. He craved the love of his audience — and his audience wanted only a representative of Spalding Gray. . . .” Samuel Beckett’s 20-minute monologue “Not I,” written in 1972 and comprised simply of a mouth moving in darkness, could have been Gray’s epitaph.

If nothing else, “The Journals of Spalding Gray” is a colorful document of the avant-garde of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s — in particular Richard Schechner’s Performance Group and Elizabeth LeCompte’s Wooster Group — out of which Gray’s work derived (Gray co-founded the Wooster Group and was romantically involved with LeCompte). Ms. Casey describes how in “Rumstick Road,” the second of a trilogy of plays called “Three Places in Rhode Island,” “he stepped forward momentarily and addressed the audience as himself, thus beginning his career — and his particular cross to bear — in offering his life as art.” The influence of previous theatrical innovators like Thornton Wilder is also obvious in this watershed moment in Gray’s career. His breaking of the fourth wall recalls the stage manager in Thornton Wilder’s “Our Town,” a role Gray would later play at Lincoln Center.

Reading these journals one is impressed with the highly aestheticized provenance of Gray’s truth-telling. Plainly the monologue was as much a theatrical as a personal form for him, despite how much he depended on the candid and at times almost sensationalized rendering of his life experience. On the other hand, the exploitation of personal experience is itself one of the darker obsessions that Gray reveals in these journals. “I felt a slight feeling of loss and bitterness that these people were using me as their jester. Their poor entertainer who used his neurosis — his life for entertainment, that I was stuck somewhere as the poor artist that people came to see, to live off my pain and to say ‘there but for the grace of . . . go I’ a kind of unhappy Christ figure — a Woody Allen Wasp that cannot love and cannot make a lot money because the audience that identifies with me has no money.”

Unlike the monologue, the journal is not a performance. There is no narrative, no story, just a succession of observations. So journals don’t carry the same burden as the performances. If the monologue gives only the appearance of truth, then a journal, which may or may not see the light of day, is more direct and immediate, a kind of free association that brooks little interference. Gray had the hope that his journals would provide “a more therapeutic way of splitting off a part of my self to observe another part.”

The problem is that many of the entries either record endless trite and confessional details about sexual episodes with himself or others or epitomize the worst of psychobabble. “Renee thinks that I am both the boy and the mother,” he says describing a conversation with Renee Shafransky, another woman who played an important role in his life. “I want to be 12 again and also be the mother of myself and that I make women like her and Liz into the father and punish them by obsessing on the boy the way my mother did with ME and that I will only STOP doing this when it causes me too much pain and disaster in my life.”

Whether the journals are more truthful or not, the watered-down psychology unfortunately reads as sententious self-dramatization. Describing a discussion about his childhood, Gray summarizes his friend Ken Kobland’s feelings about his family dynamic thus: “Mom was openly seductive with me (in the tub and elsewhere). I could not deal with it so I turned it all back on my own body and there it got stuck.”

And then there are the quotidian renderings about sex (usually good), drinking (usually too much), and therapy (unusually obtuse), which are evidentiary without being revealing — though some of these are inadvertently funny at times. Here is a description of the aftermath of one passionate lovemaking session: “ ‘Oh Spalding’ and I said ‘yes’ and she said, ‘I think I’m going to be sick’ and at last she threw up.”

There are dreams aplenty — which never seem to rise to the biblical. But isn’t that the thing about dreams? They tend to have more significance to the dreamer no matter how bizarre or prophetic. Though the diarizing often amounts to little more than verbal diarrhea, there are exceptions. In commenting on “Swimming to Cambodia,” he invokes Freud when he says, “as long as there is individuation there will be conflict and as long as there is conflict there will be war but individuation seems to be a necessary ground for being.”

Inevitably the most interesting elements of the volume turn out to derive from the editor’s attempts to correlate the actions described to historic events in Gray’s life or previously published work. For instance, the diary entry about Gray’s involvement with a young Thai prostitute named Joy is no comparison to the section describing Joy in the published version of “Swimming to Cambodia” that Ms. Casey provides.

Gray’s mother committed suicide, and these entries demonstrate the almost unfathomable power a parent’s suicide can have over a child. “Quite a number of years earlier, he had flirted with the notion that there were potential parallels between [our mother’s] life and his,” Ms. Casey quotes Gray’s brother Rockwell explaining. “That was built into his obsession with her suicide.”

In his journals, Gray has no audience to spare, and the unmediated rawness with which he confronts his own death wish, particularly toward the end when he recapitulates his mother’s earlier trauma in his own move out of a beloved house during a period of mental instability, is perhaps the most profoundly disturbing element these entries reveal. If his audience would be shaken and surprised by the lack of forthcomingness in an artist who sought to create the illusion of truth-telling, then in his journals Gray was seemingly unafraid to unravel his own dark thoughts.

On April 1, 1995, Gray made the following journal entry, “That is when suicide comes. It comes when the shadow part or let’s say the part of you that you hate starts to take over and fill up or push out all the other parts until you are all the part that you hate and there is this one little part left that is the killer and the killer is closely related to the self hate and at last it does its dirty little deed.” Knowledge of the psyche seemed to work in this nefarious way for Gray, providing the ammunition with which he was eventually able to end his life.

—

Spalding Gray lived in Sag Harbor and, later, North Haven.

Francis Levy, who lives in Manhattan and Wainscott, is the author of the novels “Erotomania: A Romance” and “Seven Days in Rio.” He blogs at TheScreamingPope.com.