Long Island Books: Truth and Fiction in Wartime

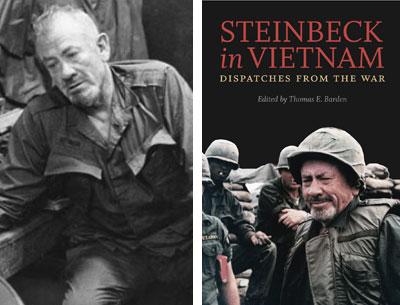

“Steinbeck in Vietnam”

Edited by Thomas E. Barden

University of Virginia Press, $29.95

When I lived in Hong Kong, in the 1960s, I’d met or heard about most of the war reporters who lived there or were passing through. How could I have missed John Steinbeck, one of my favorite writers of all time? As soon as I checked the dates of his dispatches, I realized why. A few months before Steinbeck’s arrival in December 1966, my first husband, Sam Castan, a correspondent for Look magazine, had been killed in Vietnam and I had returned to New York. It would take me far more than a few months to return to the life of the world, let alone the news of it.

Recently, I’ve spoken to people, in less extreme circumstances back then, who were also surprised to learn that Steinbeck had reported from Vietnam. Two reasons may account for this. First, his columns were published in Newsday; even with its wide circulation and its syndications, Newsday was not a primary source of international news. Second, the Steinbeck family had turned down earlier attempts to collect his Vietnam columns in a book. Apparently, they were reluctant to rebroadcast, in a more permanent format, his ultimately unpopular, hawkish position on the war.

Steinbeck a hawk! Impossible to imagine when you think of Steinbeck the novelist. I can still feel the cloth cover of “The Grapes of Wrath,” as if my palm were skimming across it, reverentially, right now, instead of half a century ago. How could this man, who chronicled the plight of Dust Bowl farmers and described the natural and human forces sustaining their misery, support a war that displaced, tormented, and maimed Vietnamese peasants? A war that would eventually kill at least two million Vietnamese men, women, and children and 58,000 Americans?

Thomas E. Barden, editor of “Steinbeck in Vietnam” and professor of English at the University of Toledo, answers many questions in the scholarly background he provides. Why, for example, did Steinbeck, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1962, become a war correspondent in 1966? After all, he was 64 years old. In Vietnam, journalists in their 30s were called “old man” by younger colleagues. It turns out that Steinbeck had been a correspondent for The New York Herald Tribune during World War II, a job he sought because he was not allowed to serve in the U.S. Army.

Now that’s a story in itself. In the 1940s, Steinbeck was regarded as an “extremist subversive” by U.S. conservatives. The F.B.I. kept a dossier on him, noting his association with “elements” of the Communist Party and the appearance of his writings in Communist publications.

The U.S. Army intelligence service wrote, “In view of substantial doubt as to subject’s loyalty and discretion, it is recommended that subject not be considered favorably for a commission in the Army of the United States.”

Here’s the amazing part. While the Army reached this conclusion, its commander in chief, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, had a personal relationship with Steinbeck and sought his advice. Among the topics Roosevelt discussed with Steinbeck was the very war the writer was not considered trustworthy enough to engage in as a U.S. soldier. Meanwhile, the “subject,” wanting to see the action for himself, managed to get an overseas assignment from The Trib.

In an odd parallel, more than 20 years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson wanted John Steinbeck’s opinion about the war in Vietnam. He asked his close friend — the Nobel laureate whom most Americans saw as morally trustworthy — to go to Vietnam as a correspondent. He thought Steinbeck’s words would promote his cause: to increase America’s involvement in a war he believed could be won.

Journalists who dared to go into harm’s way had begun to provide images that ignited antiwar sentiment in the United States. Takeovers and teach-ins on college campuses, draft-card burnings, and protest marches were making news. These forms of political expression emerged quickly and organically from struggles that yielded the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

War protesters made Steinbeck furious. He thought they should go to Vietnam and care for the wounded instead of burning their draft cards. This view may have been strengthened by the fact that his son John Steinbeck IV had just been sent to Vietnam as a soldier. His other son, Thom, also in the Army, was expected to be deployed to the war zone. Steinbeck wanted to go to Vietnam to see for himself what his boys would be facing and, most of all, he wanted to see them.

For all his liberal leanings, we are told, Steinbeck was against any system that promoted the collective over the individual. He thought the individual was both source and guardian of freedom of thought. Like Johnson, Steinbeck saw the war as a necessary means to halt the spread of Communism, but he was not comfortable going to war as a government spokesman. So, he approached Newsday’s publisher, Harry F. Guggenheim, for whom he had written before. The author was given complete freedom to write whatever he chose.

This reader instantly felt the sensation of being told the absolute truth, as Steinbeck saw it, or, perhaps, as he was assigned to tell it in what he perceived to be service to his country and to democracy. I confess it’s the first time in more than 45 years that I was able to experience pro-war words about Vietnam and not run screaming from the room — a testament to Steinbeck’s ability to convince by pure passion and by vivid description.

He very quickly perceived and conveyed how the Mekong Delta was key to feeding the entire region beyond Vietnam. He grasped the local politics engendered by a culture of rice farmers. He met American soldiers along the way and portrayed them to be as vital and heroic as his humble fictional characters. Despite the inexcusable My Lai Massacre of 1968 and other heinous atrocities that became known after Steinbeck’s death, most U.S. soldiers certainly were valiant. Steinbeck’s appreciation, had it been available to them, might have offered comfort when they returned to a scornful nation.

Praise of Steinbeck’s literary skills shouldn’t obscure the eerie confrontation with his naivete and/or his propaganda. He says that reporters had freedom to go anywhere they wished. Though there is some truth to this, most reporters partook of the military press briefings at the Rex Hotel in the city once called Saigon. Those notorious briefings came to be known as the Five o’clock Follies because of their increasingly unrecognizable relationship to what the more intrepid reporters learned in the field. And, of course, in Steinbeck’s “going anywhere he wanted to go,” he was escorted by military higher-ups. Did he really think the top brass who took him to see his son in combat, took him to what they didn’t want him to see as well as what they did?

Steinbeck himself says it best: “. . . armies haven’t changed in one respect since Roman times. They have never liked or trusted news. Given their druthers, army commands would announce victories and deny defeats and nothing more.”

Professor Barden writes that the dispatches are important and worth reading because they are the last work of a major writer. I would agree, even though they uphold fictions that did irreparable harm.

Fran Castan, who lives in Springs, is writing a memoir. She is author of “The Widow’s Quilt,” a book of poems, and “Venice: City That Paints Itself,” a collection of her poems and paintings by Lewis Zacks, her husband.

John Steinbeck lived in Sag Harbor for many years.