Long Island Books: Unto Rome

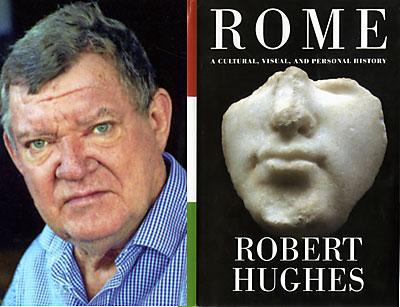

“Rome”

Robert Hughes

Knopf, $35

How does one tackle a subject as vast, complex, and full of bravado and drama as the history of the city of Rome? The answer, in the form of Robert Hughes’s “Rome: A Cultural, Visual, and Personal History,” is as an opinionated but erudite tour guide.

His 500-page opus addresses all of the highlights with slightly more in-depth examinations of particular events and personalities of note, all with the highly subjective takes on them that Mr. Hughes is now famous for, from a collection of books and television series such as “Shock of the New,” “American Visions,” and “Beyond the Fatal Shore.”

Bracketed by his first and latest reactions to a city that he describes as “one of the greatest treasures known to man,” the book introduces a place that in the era of Federico Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita” could still feel like one’s own, full of promise and artistic richness in May of 1959. Ever the cultural critic, he ends on a sour note, lamenting the obsessions with lowbrow television and soccer in the Silvio Berlusconi metropolis of today and the influx of tourists that overwhelms even less popular sites.

In between, he offers a soup to nuts, or alpha and omega (giving the city’s debt to Greek culture its due), approach to the history of Rome, from creation myth to postwar descent. The ancient statue of Marcus Aurelius, which captivated Mr. Hughes as a young man, is lamented in its current state, removed from Michelangelo’s Piazza del Campidoglio and replaced with a copy. The original is now in the Capitoline Museum and installed on a misguided slant to imply movement that Mr. Hughes finds epitomizes the condition of contemporary Rome “losing touch with its own nature, and in some respects has surrendered to its own iconic popularity among visitors.”

As his early encounter with the bronze sculpture turned art and history into reality for him, Mr. Hughes uses the visual products of the Roman imagination as touchstones for his history. Lacking factual evidence for the how and when Rome came into being, he describes the legend that places Rome’s founding at 753 B.C. on the Palatine Hill and then traces the known history from the time of the Etruscans forward. From the beginning, the Etruscans established a rich visual culture with both utilitarian ceramics and terra-cotta and bronze sculptures. Their trade with Greece and its nearby colonies in Naples and Sicily added even more beautiful objects to their legacy.

Mr. Hughes reminds us that the Etruscans were responsible for the Roman calendar of 12 months that we continue to use today in a modified form. Their alphabet and gods were likely early ancestors of the Roman versions as well, mixing with a bit of Greek tradition for the latter. From these early foundations a city rose up and became increasingly powerful by vanquishing those who set out to conquer it as it began conquering its own territory and colonies, eventually forming an empire victorious in both land and naval campaigns.

Rome’s battles with the Carthaginians led by Hannibal in the Punic Wars of the third century B.C. are notable not just for their descriptions of contemporary weaponry and sea vessels but the dissection of how Hannibal might have maneuvered 21 elephants and a force of some 35,000 men through the Alps from France into Italy. Mr. Hughes found that the favored view of scholars is that he approached from the western Alps through what is now France but was then Gaul, an ally to the North African city.

“Even if he did, the conditions they all encountered were appalling; the descending path was so narrow and steep as to be nearly impassable to horses at one point, let alone to elephants,” Mr. Hughes writes. “There is still disagreement over the usefulness of those elephants to Hannibal’s campaign, but there is little doubt that they terrified many a Roman soldier [whose ranks outnumbered the Carthaginians by 735,000 men], and the effort of getting these great beasts sliding and stumbling over the rocks and through the ice and snow of the Alps must have struck those who saw or even heard about it as astonishing.”

And that is what this book does so well. It takes historical events and astounding feats of physical and imaginative force from the ancient world through the later centuries of the second millennium and reinforces them with the latest scholarship and research. It reminds us of things that we probably haven’t contemplated since we first heard about them in high school or college and allows us to consider them anew and reconnect to their wonder.

Mr. Hughes keeps this up through empire, fall, Renaissance, Counter-Reformation, neo-classicism, modernity, futurism, fascism, and the postwar periods. There aren’t any new startling revelations, instead, as the subtitle states, personal reflections of someone who admits he never lived there but has lived on the outskirts and was a frequent visitor throughout his life. Early chapters tend to be repetitive, as if he’s getting acquainted with his audience and does not trust their attention span. Eventually, that falls away, which is fortunate because for the most part each page and paragraph is dense with information. In editing the storyline, he appears to make all the right choices. Nothing essential is missing and less common knowledge is shared.

While reacquaintance with key points in history is valuable in and of itself, Mr. Hughes also recreates the lifestyles of those periods. He likens Imperial Rome to Calcutta and observes that upward mobility of the masses, including former slaves, resulted in many a citizen who was “vulgar, gross, and a bit of a thug, like a goodly portion of the Upper East Side.”

He skirts in and out of the history of the popes, choosing only the more colorful and influential characters, such as Julius II and Pius IX, on whom to lavish his attention.

He also provides context when important events happen outside the city, managing to bring everyone back within the walls. While the Renaissance begins in the cities to the north, he reminds us that the Florentines Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello ventured to Rome to study its classical ruins some 1,000 years after they were made.

By then, the Forum was a cow pasture, and the artists had to cut through vines to measure and draw fallen arches and column fragments. “Nothing was self-evident as the Roman ruins are today,” Mr. Hughes observes. The inclusion of this story seemed gratuitous at first, but then essential to understanding how the Florentines continued to gather influences aside from just the relics collection of Lorenzo de Medici. When he credits Brunelleschi with finding the keys to linear perspective in these drawings, it is clear there really is no other explanation.

Mr. Hughes’s reputation precedes him, and it would not do much good to his effort not to mention his treatment of artists active in Rome over many centuries. While the book boasts an extensive bibliography, there are no footnotes. So when the author says that Michelangelo claimed all credit for the subject matter of the Sistine Chapel, “but he was given to claims like that,” we have to take him at his word.

His fans will no doubt enjoy his longish (no digression, no matter how meaningful, can be more than a few pages in such a survey) encomiums on his favorite artists, including Michelangelo, Raphael, Bramante, Bernini, Caravaggio, Carracci, Poussin, Lorrain, up to a grudging acknowledgment of Giorgio de Chirico and the futurists, at least in some cases.

One puzzling element, however, is Mr. Hughes’s well-reasoned arguments in favor of the once (and still, in some circles) controversial restoration of the Sistine Chapel frescos of Michelangelo. They contradict the prerestoration reproductions of the same frescoes included in the book. It is obviously a production versus editorial glitch, but anyone who casually skims the book would have an inaccurate impression of the author’s allegiances in this skirmish, which has divided art historians for decades.

Other than that, there are few false notes. In fact, each chapter, each page, each paragraph, sentence, and word sings out over the centuries with an assuredness we have come to expect from such a discerning voice. Even if one does not always agree with him, no one will find taking the time to discover his predilections an empty exercise.

Until an auto accident a few years ago, Robert Hughes lived on Shelter Island, where he beat off sharks with a baseball bat, among other tales apocryphal and strangely factual.