Long Island Books: A Vanished World

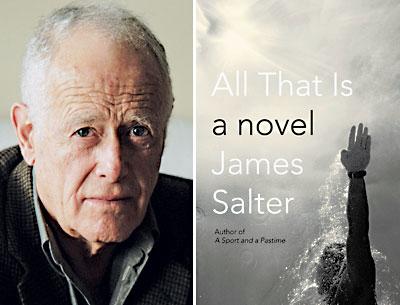

“All That Is”

James Salter

Knopf, $26.95

In the kind of world James Salter writes about, the writer James Salter would no doubt be a household name. The characters in his novels, for the most part, seem to live on a different aesthetic plane from the rest of us. They know literature, wine, good food, the great cities of Western Europe, architecture, and a good deal about sensuality. In this enlightened universe, Mr. Salter’s fourth novel, “Light Years,” would be as widely read as the books of Tom Wolfe, say, and soccer moms in search of an erotic charge might pass around his third book, “A Sport and a Pastime,” rather than “Fifty Shades of Grey.”

As it stands, though, the world is a far more parochial place, and James Salter the novelist remains in the margins of contemporary fiction — albeit with a very large asterisk, one reserved for writers who are not widely read but greatly admired. I can tell you that this is as tedious a sentence to write by now as it must be for James Salter to hear; this has been said too many times for too long. And yet it needs to be said — he is a truly great American writer who has somehow slipped through the cracks of the culture.

His new novel, “All That Is” (his first in over 30 years), probably won’t do much to change this, though it does inch, grudgingly, toward a larger audience. It is perhaps the most approachable of his books. And then hope always springs eternal for the novelist; Mr. Salter turns 88 this June.

As if propelled by this sense of encroaching time, “All That Is” begins, quite literally, with guns blazing, the first chapter a bravura rendering of World War II in the Pacific. We follow a 20-year-old Navy officer, Philip Bowman, during the Americans’ costly and excruciating march toward Japan. It is huge set piece compressed to miniature — a mere 10 pages — and yet Mr. Salter’s prose never allows the chapter to feel dashed off or superficial. Of the Japanese Navy, who are on a suicide mission, the author says, “They had written farewell letters home to their parents and wives and were sailing to their deaths. Find happiness with another, they wrote. Be proud of your son.” As the bombarded Japanese ship is ready to go down, he writes, “It was not a battle, it was a ritual, the death as of a huge beast brought down by repeated blows.”

As the war ends, Bowman heads toward New York, the “great city,” in Mr. Salter’s eyes. There Bowman stumbles into publishing, and thereby begins the life that seems to stand for the author as the quintessential postwar American experience. There are the girls in P.J. Clarke’s, the office parties, great dinners, love affairs, marriage, divorce, the move to the suburbs, business trips to Europe, betrayal, and finally rebirth. This is the real subject of “All That Is”: the arc of a full life lived at the second half of the last century.

Critics of Mr. Salter’s work — yes, there are a few — often take him to task for a kind of preciousness of style, if not mise-en-scene. For some, the premier cru Burgundy, the just placed flower vase, the luncheons out of a Manet painting, can smack of lifestyle writing. For others, the lyrical compression of his prose style can seem overwrought, if not pretentious. (Clearly I am not of this camp.) Either way, Mr. Salter’s new novel should temper these criticisms. The writer we encounter in “All That Is” is a less ecstatic one than the writer of “Light Years” and “A Sport and a Pastime,” both in its set pieces and its prose. There is a sober directness to this book, as if the author made a conscious effort, as William Faulkner once advised, to “kill all his darlings.”

That is not to say the author has become pedestrian. For fans of the Salter flourish, “All That Is” holds plenty of gems: “Bowman was feeling the drinks himself. Among the brilliant bottles in the mirror behind the bar he could see himself, jacket and tie, New York evening, people around him, faces.” Soldiers in the Pacific are “slaughtered in enemy fire as dense as bees.” In the back of a taxicab with a woman, Bowman sees the Manhattan skyline in the distance, “a long necklace of light across the river.” And here is the editor Bowman at night: “He liked to read with the silence and the golden color of the whiskey as his companions. He liked food, people, talk, but reading was an inexhaustible pleasure. What the joys of music were to others, words on a page were to him.”

You either respond to this sort of thing or you don’t. If you don’t, you may not find “All That Is” particularly nourishing. As ever, James Salter is a writer who exalts in the small moment, the brushstroked image. Excepting a scene of shocking sexual revenge toward the novel’s end, this is not a story of high-arcing trajectory; this is a realistic portrait of the ebb and flow of a postwar life. His hero, Philip Bowman, loves deeply, hurts deeply, and, like most of us, somehow endures. End of story. Yes, stylistically Mr. Salter has tempered, but as a dramatist, he has not changed — he meets you half way and no more.

This, I believe, is the crux of what has kept this writer from the mainstream for so long. You need to know something of life, of experience, to enjoy Mr. Salter’s universe. You need to share some of his sensibilities. And, as with the very best novels, you need to bring some of yourself, your own riches, to the party, or risk being left to stand in the corner, feeling resentful of the others’ good time.

For those who do respond, “All That Is” will be a novel of great pleasures. You will read it slowly, savoring passages, occasionally going back over a sentence that, like a crisp jab, catches you emotionally off-guard. Other moments you will see some of your own life passing before you on the page. Finally, you will be comforted that someone believes some of the same things you do, and lament the passing of a no less cruel, but somehow less juvenile, world.

Then perhaps in a few years, you will run across the novel again and, remembering the pleasure it gave you, reread it to see if you can get some of those pleasures back, to convince yourself you were right about it the first time.

And because of James Salter’s extraordinary and singular talents, you will be.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.

James Salter lives in Bridgehampton.