A Long, Slow Revolution

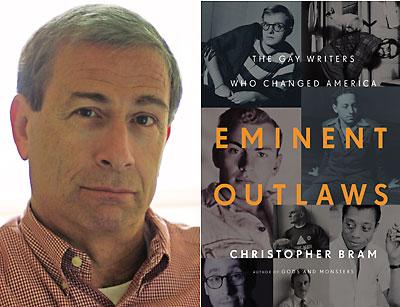

“Eminent Outlaws”

Christopher Bram

Twelve, $27.99

What would American literature look like without contributions from gay writers? Think of a canon without “A Streetcar Named Desire,” “In Cold Blood,” “Angels in America,” “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf,” or the essays of Gore Vidal and James Baldwin. It isn’t pretty to think so (and these are just the men). While many of these works will live on indefinitely, what is often overlooked is the indifference, resistance, or often outright hostility these writers endured in both their private and professional lives. It is this struggle, and these writers’ role in carving out what would eventually become a gay American “mainstream,” that Christopher Bram explores in his new book, “Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America.”

Mr. Bram begins his tale in the late 1940s, in (where else?) Times Square, where a young Gore Vidal is working as a part-time book editor by day and picking up male hustlers by night. He also finds time to write a novel, “The City and the Pillar,” which may be the first direct account of male homosexuality in a widely published American novel. Vidal was a sergeant in the Navy, too, a fact that figures widely in Mr. Bram’s thesis. It was the mass mobilization of the war itself, he posits, that threw together Americans from different parts of the country and “which first made the idea of homosexuality more amenable to American culture. Men who liked men and women who liked women found they were far from alone.” While gay American writers had previously kept their mouths shut about their sexuality, at least in their fiction — Henry James, Hart Crane, Thornton Wilder — writers now had a new freedom to speak more directly about their inclinations.

Things hardly changed overnight, however. Along with Vidal’s novel, Truman Capote would publish “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” a book that made more gentle allusion to homosexuality, but which garnered the same tepid reviews, or worse: “disgusting,” “sterile,” and “gauche” for Vidal; Capote, meanwhile, “has talent, but it is not a promising talent; it is a ruined one.” Tennessee Williams succumbs to the pressure to tone down the homosexuality of his hero Brick in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” with so many different drafts, Mr. Bram speculates that the famous exclamations of “mendacity!” are partially Williams chafing himself over his own artistic integrity.

By the time Allen Ginsberg publishes his epic poem “Howl” the knives are out, and an obscenity trial follows. The liberality of the postwar years has evaporated and many gay writers return to the closet — or is it just their characters? As his book moves through the early 1960s, Mr. Bram does a terrific job of covering the sometimes ugly accusations that the “straight” work of gay writers was in fact simply a foxhole for gay themes; it was widely argued, for example, that the combative husband and wife of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” were really just a bickering gay couple. Why so many straight couples saw themselves so completely in Martha and George — or if it mattered whether the author, Edward Albee, drew them from gay characters or not — was never considered.

As we move into the ’70s and early ’80s, though, Mr. Bram’s book loses steam — always in direct proportion to the gradual acceptance of gay culture. In fact, I’m not sure that Mr. Bram ever satisfactorily proves his thesis, that it was gay writers who made the culture more accepting of homosexuals (rather than the changing culture making these artists’ success possible). Is there a natural line connecting, say, Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, and Tennessee Williams to “Will and Grace,” the sitcom so often cited as the touchstone of a gay infiltration of mainstream America? That seems a tenuous connection at best.

And I’m not sure that, however besieged they were or felt to be, most of the writers in this collection can fall under the moniker of “outlaw.” The majority of writers explored here were highly successful establishment icons whose works flourished. Many became fixtures on the TV talk show circuit, and a handful, at least, even grew rich. Jean Genet was an outlaw; as for Tennessee Williams, I believe the term “genius” will do.

But so what if Mr. Bram’s book doesn’t quite live up to the grandness of its title; it is still a sizable accomplishment — a history of gay men’s contribution to American literature in the second half of the 20th century. If these writers didn’t single-handedly create an American acceptance of homosexuality, they certainly played their part. I only wish the Rick Santorums of this world would read Mr. Bram’s book, or better yet, some of the actual works of these great authors.

But then some people only need one book.

Christopher Bram’s novels include “Father of Frankenstein,” which was made into the movie “Gods and Monsters.” Of the subjects of “Eminent Outlaws,” Edward Albee lives in Montauk and Truman Capote lived in Sagaponack.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels “Lit Life,” “Gotham Tragic,” and “Exposure.” He lives in Springs.