Lord Lucan Is Back

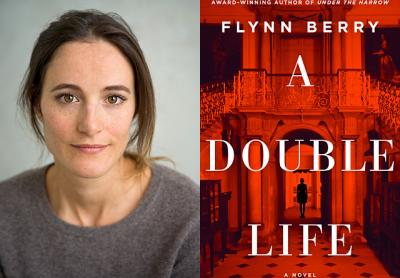

“A Double Life”

Flynn Berry

Viking, $26

Those who disappear seem to have a tenacious hold on the collective imagination. In 1974, a wealthy, charismatic British aristocrat, Richard John Bingham, the seventh Earl of Lucan, vanished after — as far as we know — killing his children’s nanny at their posh London home, having mistaken her for his estranged wife. He left behind an irresistible pall of intrigue, and strange theories proliferated over the years, from his drowning in the English Channel to his living in India as a banjo-playing hippy called Jungle Barry. There was even a far less prosaic ending suggested when a claim surfaced that he had been fed to tigers in a private zoo in the English countryside.

Despite his being officially declared dead by the British High Court in 1999, the Lord Lucan mystery continued to pique lurid fascination and excite conspiracy theorists. Today, it remains a story unlikely to ever have a complete ending.

An American author, Flynn Berry, a longtime summer resident of Amagansett, has decided to at least fictitiously resolve this real-life mystery in her astute new thriller, “A Double Life.” This is her second novel, following “Under the Harrow,” a 2017 Edgar Award winner for best first novel.

In “A Double Life,” Ms. Berry reimagines the real-life story by staying true to many of the details of the crime — although moving the action forward a couple of decades — while fictionalizing the characters. The narrator here is Claire Alden, a seemingly ordinary 34-year-old physician living in north London. But she’s really the daughter of Lord Colin Spenser, who vanished 26 years earlier, in 1992, after becoming the prime suspect in a brutal attack on Claire’s mother and nanny. (His character is perhaps the least fictitious, right down to his partying ways and the Eton education. Also interesting is the use of “Spenser” as his surname, which could be a nod to Spencer, Princess Diana’s maiden name, a family to which Lord Lucan was related.)

After her father’s disappearance, Claire and her family fled to Scotland, where they assumed new identities but remained haunted by the tragic past. Now an adult, with a brother who is struggling with addiction (“Robbie looks like our father. Sometimes I wonder if that’s why he mistreats himself. It’s the only act of revenge he can take”), Claire is understandably consumed by the possibility that her notorious fugitive father might still be alive. She hangs on to this possibility obsessively; it’s the only way she might ever find out what really happened on the fateful night.

In satisfyingly ominous prose we also learn of Claire’s seething rage: “It isn’t him. I call the dog, I say sorry in a strained voice. The path is narrow here, we have to pass within a few inches of each other, and I look at him again, to be sure. Then I clip the dog’s leash and hurry towards the houses and people on Well Walk. I wish it had been him, and that instead I was searching the ground for a heavy branch, and following him into the woods.”

Complex characters, especially the blue-blooded dastardly villain (“He’s a hedonist. That’s part of my fury — during all of this, even now, he’s somewhere enjoying himself”), are brought heartbreakingly to life while Britain’s unjust, and still prevalent, class system, which lies at the heart of this tale, lends the narrative some moral weight.

Ms. Berry paces her storytelling well, alternating between Claire’s present-day investigations and the patching together of memories and stories from her mother’s diaries of her married life almost three decades earlier. In doing so, the reader uncovers a young woman both defined and imprisoned by a past. Hers is a world falling silently apart, the innocent victim of a dreadful moment that changed everything utterly, like the floor dropping out from beneath her, so that all she is left with is a life that curdles into something more crippling and disturbing.

Here, she remembers the last time she saw her father, when he gave her a candy cane from the top of his ice cream: “He might have already made the weapon before we sat together in a booth at Luxardo’s. It’s difficult for me to think of that visit. Not because I could have stopped him, exactly, I was eight years old. But the scene seems grotesque. The little girl accepting the red-and-white candy from him. It’s like he made me complicit.” (Note: It’s highly unlikely for an English native to say “candy.” She would have said either “sweet” or “peppermint stick.”)

Although her sleuthing is perhaps the story’s weakest link, especially the blackmailing that eventually leads to a crucial lead, “A Double Life” culminates in a pretty gripping and plausible conclusion.

That an American author too young to have lived through the actual Lucan mystery chose a very British story to retell as her own solidifies the fact that, along with royal weddings and colonialism, Britain rules when it comes to crimes featuring colorful miscreants.