Lou Stillman’s Filthy Gym, by Jeffrey Sussman

I was a short, skinny teenager, and my father was concerned that bigger boys might pick on me. My father, who was a skillful boxer and friends with the heavyweight contender Abe Simon and other boxers, knew Lou Stillman, the owner of Stillman’s Gym. The place was named “the University of Eighth Avenue” by A.J. Liebling in a New Yorker magazine article.

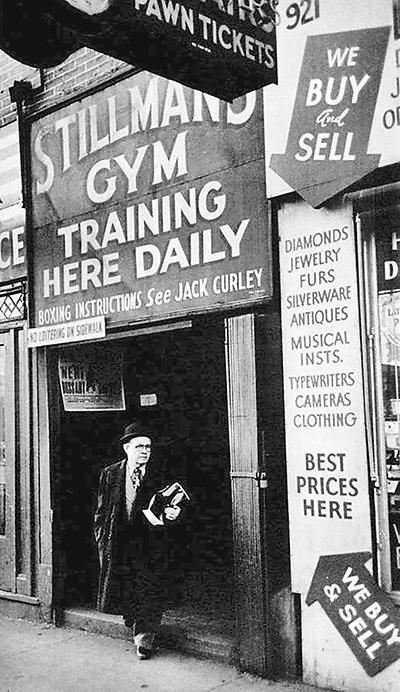

My father drove us into Manhattan from our home in Queens and found a parking space on a side street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. We arrived at 919 Eighth Avenue and went up a flight of stairs. There was Mr. Stillman, sitting at a desk near the door. He had a big, ugly cigar that smelled like rotten cabbage stuffed into his face. Hair billowed out from the sides of his head. He wore a shoulder holster that contained a snub-nosed .38.

“Howyadoin’ Bob?” Mr. Stillman said to my father.

“This is my boy. I want him to have those 10 lessons that I called you about.”

“It’s all set,” said Mr. Stillman. He called over his manager, a guy named Jack Curley.

My father handed over several bills, and Mr. Stillman called over a young middleweight, a good-looking Italian kid with dark, curly hair.

“I’m Nick. Follow me, kid,” he said.

He led me through one of the filthiest gyms in existence. It smelled of sweat and liniment. There were the sibilant sounds of soft-soled shoes skipping rope, the thwack-thwack-thwack of gloves hitting heavy bags, and the quick pop-pop-pop of gloves against speed bags.

Nick took me to a locker where I changed out of my jeans and polo shirt. I put on a cup, a pair of shorts, and a Stillman’s Gym T-shirt, and was then led to a heavy bag. Nick had me stuff my fists into a pair of large boxing gloves, then tightly tied them in place. He taught me to jab with my left, punch straight out with my right, and deliver an effective right cross.

“Always keep that left jabbing like a jackhammer,” he said. “And when your opponent can’t take his eyes off that jab, smack him with a right cross. Jab again and then deliver a right uppercut. That should stop him.”

In addition, I learned to duck, to feint, to swing a left to the body and a right to the jaw. I learned how to protect my head and to look for openings. I learned how to create openings. Nick had me shadowboxing and skipping rope. But he wouldn’t let me get into one of the rings. “You’re too young,” Nick said. “You’ll get killed.”

Nevertheless, I loved it and became a fan of boxing. I attended those sessions for 10 Saturdays and felt that I had learned to protect myself against bullies. Upon my graduation, I was given a Stillman’s T-shirt, though I suspected that my father had to pay for it. Stillman was not known for giving away his merchandise, though I later learned that he often staked some poor fighters.

Lou Stillman was a character out of a Damon Runyon story; he could have played himself in “Guys and Dolls.”

So who was Lou Stillman? He allegedly started out as cop named Louis Ingber. He left the police force and got a job managing a boxing gym called Stillman’s that had been started by a starry-eyed philanthropist named Marshall Stillman. It was Stillman’s idea to save poor kids from lives of crime by teaching them to box. He hired Lou Ingber to manage the gym after meeting him on a trolley car. They apparently had shared a seat and engaged in conversation about the day’s social problems.

Stillman’s initially became a mecca for young Jewish boxers, led by the lightweight champion Benny Leonard, who had left another gym after its owner claimed that World War I was started by Jews and “those people are responsible for all the wrongs of the world.”

Since Ingber managed the place, the boxers referred to him as Mr. Stillman. Lou conveniently changed his last name and went on to become a boxing legend, as did his gym. Some of the greatest champions trained at Stillman’s, including Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Rocky Graziano, Max Baer, and many others.

Stillman charged a couple of my friends 50 cents each for watching champs and contenders train. The gym also became a hangout for managers, promoters, gangsters, bookies, and sportswriters.

The place was probably the filthiest gym in New York. The floor was one gigantic spittoon; the windows were dark with grime and never opened. Stillman claimed that fresh air was bad for fighters. “It’ll kill ’em.” He added, “The golden age of prizefighting was the age of bad food, bad air, bad sanitation, and no sunlight. I keep the place like this for the fighters’ own good. If I clean it up, they’ll catch a cold from the cleanliness.”

Lou was known as a tough guy; he had a hair-trigger temper and could let fly an array of foul-mouthed epithets at anyone who made him angry. He was not intimidated by the biggest boxers, or by the gangsters who were always on the lookout for a fight to fix. And none of his targets ever responded in kind. They took Lou’s abuse as if it were part of the price to pay for being in Stillman’s Gym.

In 1959, Stillman’s Gym was targeted by the wrecker’s ball and cleared from its site to make room for an apartment building. Today there is no sign to commemorate the legendary gym; it is known by those who visited it, worked out there, and learned the trade of boxing. It’s a fond memory for a dying generation, and soon Stillman’s will exist only in the evanescent works of a few writers and as background in some movies.

If you want to catch glimpses of Stillman’s and enjoy a great boxing movie, watch “Somebody Up There Likes Me,” starring Paul Newman as Rocky Graziano. One old boxer told me it brings tears to his scarred eyes and a smile to his weathered lips.

Jeffrey Sussman, who lives part time in East Hampton, is the author of "Max Baer and Barney Ross: Jewish Heroes of Boxing," which comes out on Nov. 16.