The Magnificent Dispersal

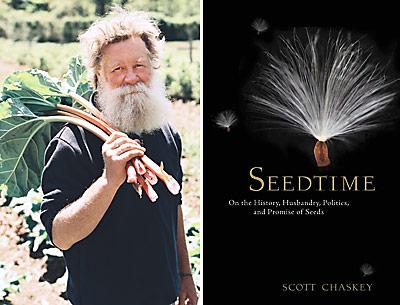

“Seedtime”

Scott Chaskey

Rodale, $23.99

An unassuming byway off Deep Lane in Amagansett, crowded with brambles common to Long Island, leads to where members of Quail Hill Farm are told by chalkboard what’s available for harvest this week. When you reach the fields, if you look closely at the rows of vegetables, you’ll see they cohabit with weeds (no herbicides applied here). The fields generally look as though the farmers have more work than they can finish. It’s all so low-key, a first-time visitor might whisper to a companion, “This does not seem like the fabulous Hamptons I’ve heard so much about.”

Your first sense that Quail Hill may be hallowed ground arrives when you see the milkweed with monarchs flitting from flower to flower. Glance around and you will spot the Quail Hill prophet, right over there with his foot on a hay bale. A thicket of white beard sprouts from his face, and there’s a circle of followers. If he weren’t already so well known as Scott Chaskey, I’d call him Jeremiah, whose task was to remind Israel about their covenant with Yahweh and the consequences of their ignorance of the covenant.

Mr. Chaskey’s task is to remind us we have a covenant with nature and there are consequences of ignoring that covenant. This covenant exists ipso facto because we live on the earth and depend on it for life. His new book, “Seedtime,” is this era’s The Book of the Prophet Jeremiah, the literary prophet. Like Jeremiah, Mr. Chaskey’s book is beautiful literature with a dreadful warning.

Scott Chaskey is a farmer. He has worked the land of Quail Hill Farm for the Peconic Land Trust for a quarter of a century. He is a pioneer in the community farm movement with all that implies; he grows food in the most wholesome and healthy way it can be grown for the farm’s members and the area’s restaurants; he trains people to do the same thing with an intern program, and he leads organizations that educate and promote healthy farming practices throughout the country and, yes, even worldwide.

At the same time, the farmer is a poet and scholar. “It took several hundred million years or more to move from the birth of a single cell to the evolution of seed cones to the formation of seeds,” he notes, “and yet we now take for granted this magnificent dispersal — the language of transport of the plant kingdom — as if it were simply a mechanical inevitability rather than a mysterious gift of time.” No one can grow food the right way without humility, without a little perspective on the relative place of mankind in the time of the universe. “Seedtime” prods us to regain the sense of reverence needed to protect the earth and its abundance. That respect glows from the book.

A prophet is also a teacher, and there is much to learn from Scott Chaskey: the history and nature of seeds, the difference between an open-pollinated seed and a hybrid seed, and what a GMO is and how it is genetically modified.

Mr. Chaskey states: “Hybrid seeds are not inherently evil, and more often than not our farm members are surprised to hear that we purchase and sow hybrid. . . .” But here’s the problem: If you choose a hybrid and learn to love it, say for instance a tomato, you are then tied to a seed company in order to secure the seed for next year. Thus begins the process of decreasing biodiversity. “Our increasing tendency to homogenize all aspects of our ecosystems limits our ability to adapt to ever-changing conditions of climate and culture.”

A prophet, by necessity, has a stern nature. “Thus saith the Lord of Hosts, ‘Amend your ways and your doings, and I will cause you to dwell in this place. Trust ye not in lying words.’ ” Jer. 7:3-4.

Mr. Chaskey speaks: “Now I am compelled to write in response to the urgent needs of planet Earth and to recover some sense of balance in our understanding and care for the land, in how we choose to manage and distribute seeds and to grow the food that sustains us.”

He both explains the process and warns about the transgenic methodology responsible for GMOs (genetically modified organisms). There are the known consequences, the reduction in biodiversity, as powerful seed companies try to get every farm to grow plants with their seed. Then there are the as yet unknown possible results.

In natural breeding, new kinds of chickens can be obtained by breeding a chicken of one variety to a chicken of another variety in order to enhance certain desired qualities. Transgenic breeding is like mating a chicken with a mouse or a potato. The long-range result of changing edible plants and animals by the transgenic method currently is unknown.

The argument in favor of GMOs is that they produce a greater yield than traditional varieties or even hybrids. The yield is needed to feed a hungry planet. So far, the argument has been persuasive. Mr. Chaskey reports that by 2010 in the U.S., 93 percent of soybean acreage, 63 percent of corn acreage, and 78 percent of cotton acreage were planted with GMO seed. One known result: less biodiversity. In the Philippines, there were once thousands of varieties of rice. Today, two varieties account for 98 percent of all rice grown. Think! Ireland. Potatoes. Blight. Famine.

Jeremiah warned Israel if they did not honor their covenant with God, the enemy from the north, the Babylonians, would carry them into captivity. Mr. Chaskey warns, “As we face the challenges of climate change and the loss of prime agricultural soils, we need a diverse seed supply to counter the unpredictable and the unknown. Instead, we continue to lose plant species — and the seeds of the future — at an alarming rate.” The diversity found in seeds is nature’s way of providing food for the earth. The destruction of biodiversity is the Babylon that threatens us.

Mr. Chaskey and other leaders of the biodiversity movement believe variety is the ultimate form of food security. “A holistic agricultural system, innovative by definition, includes different cultures and numerous producer-consumer relationships. ‘Freedom of Seed’ proclaims the right of farmers to save seeds and to breed new varieties, to exchange and trade seeds, to have access to open source seed (seed free of patents), and to be protected from contamination by GMO crops.”

Jeremiah spoke Yahweh’s message. “I brought you into a plentiful country, to eat the fruit thereof and the goodness thereof; but when ye entered, ye defiled my land, and made mine heritage an abomination.” Jer. 2:7.

With the striking language of his art as a writer, Mr. Chaskey in “Seedtime” conveys the voice of the natural world. “Seeds, like words, ‘behave like capricious and autonomous beings,’ so if we give them space to perform, perhaps we stand a chance to inherit their intelligence. This seems like a wiser choice to me, rather than to force our intelligence upon them.”

The author of “Seedtime” works a farm in what was once a humble farming and fishing community. His book is dense with language, information, insight, and hope. Remarkably, the book’s message is not strident, considering the strength of Babylon, the companies that seemingly will do anything to protect their perceived right to dominate the distribution of seeds through patents and legal maneuvers. The word about the threat is out, in newspapers, magazines, and all media. You see the pieces from time to time, mostly balanced with both points of view that I’d summarize as, “No GMOs,” “Yes GMOs.”

Now, this era’s Jeremiah has spoken. What Scott Chaskey works at in his small sphere of influence, an organic farm, seems tiny as a clover seed when compared to the enormity of the problems of world hunger and climate change, as well as the resources and the will of corporations to dominate governmental policy regarding seeds. However, without those tiny seeds sown by Mr. Chaskey and others, where would we be? “Behold, a sower went forth to sow; and some seed fell on good ground and brought forth fruit, some an hundredfold, some sixty fold, and some thirty fold.”

“Seedtime” is the most elegant and comprehensive description yet written of the fierce battle being waged over biodiversity.

Gary Reiswig lives in Springs and grew up on a farm in Oklahoma that harvested the best of each year’s crop for next year’s seed. His new book, “Land Rush: Stories From the Great Plains,” will be released soon.

Scott Chaskey lives in Sag Harbor. He will read from “Seedtime” at Sylvester Manor on Shelter Island on Friday, March 21, at 7 p.m.