Making the Most Of Minimalism

It’s rather odd to think of a show of Minimalism in a place like Guild Hall, which has historically dedicated itself to more homegrown art. Minimalism seems anything but, which is why “Aspects of Minimalism” is exciting and almost a bit naughty, as if the museum were cheating on its partner.

When you think of the East End, Minimalism is not the first movement, or even the 21st movement that comes to mind. On the early side of the art colony’s timeline, there are the sweeping Western landscape vistas of Thomas Moran that he painted in East Hampton from his in situ sketches as well as the more intimate settings he chose as subjects here. Other 19th-century and early-20th-century painters such as Childe Hassam and William Merritt Chase were also active here.

The next significant artistic influx came after World War II, when several members of the New York School found second homes and studios here. This group’s highly personalized, even emotional visions, executed with gestural marks and imprints clearly in the artist’s hand, were everything that Minimalists reacted to in their emphasis on mechanical and orderly processes. Their materials, mostly industrial and often fabricated or mass-market, were executed with rigid geometric and linear forms.

Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol represented American Pop Art in the 1960s and ’70s, taking up residence in Southampton, East Hampton, and Montauk respectively, and then the next wave came in, with painters who hit their stride in the 1980s — Eric Fischl, Ross Bleckner, and Julian Schnabel and members of the Pictures Generation such as Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince. Artists associated with the original Minimalist movement such as Dan Flavin and Frank Stella found their way here, but they were the exceptions. The most clear connection the exhibition has to the South Fork is the primary lender, Leonard Riggio of Bridgehampton.

The show’s title makes it plain that the guiding principle of its organization is less strident and more spiritual, which gives the exhibition a kind of inclusionary warmth it might not otherwise have.

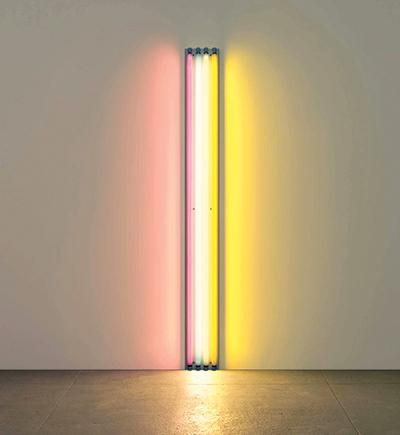

The installation displays several Flavin florescent pieces and Robert Irwin’s more recent interpretation. There is no Stella, but the broad net brings in a number of exciting proxies such as Joseph Beuys, Blinky Palermo, Rachel Whiteread, Gerhard Richter, and Edward Ruscha.

The traditionalist old guard is represented here as well with a couple of strong Agnes Martin paintings, two Donald Judd sculptures, and a glass cube by Larry Bell. They are joined by some proto-Minimalists such as Josef Albers. Bridget Riley, On Kawara, and a very uncharacteristic painting by Warhol round out the group of 12 artists represented.

It is the Warhol that stands out, mostly because it is unexpected and seems to relate more to the Abstract Expressionist aesthetic. The silkscreen process and synthetic polymer that helped create the work does allude to mechanical fabrication, but the resulting canvas sure doesn’t look like it. Sea green takes up the top and right side of the canvas in varying densities. Another band of the color near the bottom looks like a gestural green slash. What also makes the work stand out, since this is a collector’s show, is that it is so unlike the classic Warhol oeuvre. Given the inordinate amount of consideration the art market holds in determining aesthetic value, most collectors in it for the investment value would never choose a work so far outside of the artist’s norm. It is commendable that someone let their taste and intellect guide them in a purchase, rather than the dictates of resale.

The fact that the Flavins are all from the same year or so, 1963-64, captures the artist at a moment in time. Conversely, the broad range of dates of Donald Judd’s work underline the consistency the artist has adhered to throughout his career.

The English artists Bridget Riley and Rachel Whiteread are both bracing choices, again mostly for the unusual experience of seeing them here. Ms. Riley’s Op Art provides at least 20 percent of the vibrant color in a show that features a great deal of tonal work. The paintings look gleeful and irreverent compared to their often-somber neighbors. Ms. Whiteread’s casts of both a window and a brick wall laid over each other offer a dose of urban-inspired claustrophobia. The work’s linearity and flattened pattern could be seen as merely geometry to a purist, but its psychological effect is undeniable.

The exhibition remains on view through Oct. 10. Ms. Strassfield will give a talk in the gallery on Sept. 17 at 2 p.m. The museum will gather a group of regional artists to give their response to the works in the show on Oct. 1 at 2 p.m.