A Man of Midcentury Anguish

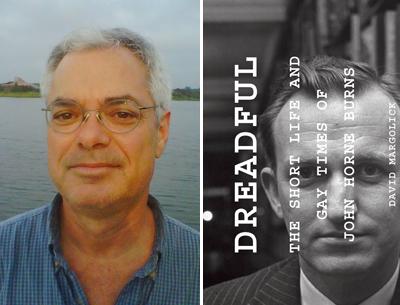

“Dreadful”

David Margolick

Other Press, $28.95

Soon after the journalist and author David Margolick entered the Loomis School in Windsor, Conn., in the fall of 1966, he became aware of a particularly captivating bit of school lore: A generation or so earlier, a Loomis English teacher, who had already made a name for himself as the author of a celebrated novel set in World War II Italy, had written “a scabrous novel about Loomis called ‘Lucifer With a Book.’ It was . . . filled with thinly veiled caricatures of its teachers, many of whom were still there, the people we saw walking around every day.”

That the satire was banned from Loomis’s own library only intrigued Mr. Margolick the more and impelled him to find out all he could about the book’s author, John Horne Burns, and about Burns’s life, his literary output, and his Loomis career. The result of Mr. Margolick’s decades-old fascination is “Dreadful: The Short Life and Gay Times of John Horne Burns,” published earlier this month.

A longtime contributing editor for Vanity Fair (before that he was the national legal affairs correspondent at The New York Times), Mr. Margolick brings to this study of a now-forgotten author his considerable skills as a researcher and writer. The 437-page biography reads easily. It is a comprehensive reconstruction of an idiosyncratic life in a peculiar time.

The two overarching elements of that life, apparently, were Burns’s intelligence and his homosexuality. They defined the arc of his existence. One accounted for his rise; the other, for his precipitous descent.

He was born in 1916, the eldest of seven children in an Irish-Catholic family in Andover, Mass. Educated at Phillips Academy there, he went on to Harvard, where he majored in English and graduated having earned membership in Phi Beta Kappa.

Accepting a teaching position at Loomis, an independent boys’ secondary school founded in 1914 (it merged with the nearby Chafee School in 1970 to become coeducational), was something of a compromise for Burns; he had sought employment at more prestigious institutions. Once there, however, he gave it his all, holding his students to high intellectual standards and becoming the sort of sardonic teacher one often finds at prep schools — a type whose combination of brilliance and haughtiness creates a cult of personality that invariably ensnares certain of their pupils and turns them into acolytes.

One former student recalled a Burns lesson on how to distinguish a major poet from a minor one. “ ‘Now which is Edna St. Vincent Millay?’ he asked. ‘Clearly minor,’ several students replied. ‘No, of course not, you fools,’ he snapped back. ‘Anyone with the name Edna St. Vincent Millay is a major poet! Obviously!’ ”

“John Horne Burns was the best teacher I ever had anywhere, in anything,” reported another Loomis alumnus.

What might have been a satisfying life and career for many, failed to engage and satisfy Burns. While at Loomis, he wrote and destroyed several novels and began to leave campus whenever he could, presumably to pursue a clandestine gay social life away from the scrutiny of the school community.

When the United States entered World War II, Burns had his excuse to escape what had become an oppressive existence at a New England boarding school. He entered the Army as a private and in short order was commissioned as a second lieutenant. His knowledge of several languages was put to use in various noncombat jobs in Morocco, Algeria, and Italy.

The life of an American abroad appealed to Burns, who applied for work at the State Department following his discharge from the military in 1946. “They’ll take me for my snob value and education,” he predicted with some arrogance. But they didn’t. Turned down — presumably because of his homosexuality — Burns returned to Loomis for a year, during which time he wrote the novel that would bring him fame and, to a lesser degree, fortune.

Published by Harper & Brothers in 1947, “The Gallery” was a somewhat controversial book. A novel created as a series of portraits of people whose lives intersected during the war at the Galleria Umberto, a Naples shopping arcade, it was considered unflattering to Italians and Americans alike. Moreover, it did not shy away from dealing explicitly with sexual matters (including homosexual matters) at a time when this was considered out of bounds for cultivated literature.

Though far from universally acclaimed, “The Gallery” earned praise from such cultural and literary lights as Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos, and Ernest Hemingway, among others. The attention and the royalties that accrued from the book enabled its author to leave Loomis and America for good, establishing himself as an expatriate writer in Florence in the late 1940s.

His next two novels, “Lucifer” (1949) and “A Cry of Children” (1952), brought increasingly negative reviews and declining income. Burns, who had been drinking heavily for years, was by now probably an alcoholic. His life in Florence revolved around the bar at the Hotel Excelsior, where he became a fixture and held court nightly.

Following a sailing trip in August 1953, Burns suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died in a Florence hospital. He was 36.

At first blush, it is difficult to discern the underlying objective of Mr. Margolick’s enterprise here. One might suspect that it is to redirect the spotlight on, and rehabilitate the image of, an author of merit who has fallen into near-total obscurity. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Mr. Margolick argues neither that Burns’s life was exemplary (or even admirable), nor that his literary output deserves rediscovery.

What we are left with, then, is a description of the corrosive effect of being gay in midcentury America on a person who was evidently intelligent, well educated, and talented. Like so many of his generation, Burns struggled with the overbearing pressure of being homosexual in a pervasively homophobic world, especially in a Roman Catholic family in New England. Although he himself made no secret of his sexuality, he was also self-loathing for it. The book’s very title, “Dreadful,” refers to a Burns code word for gay people; he used it as a noun, referring to himself and his gay counterparts as “dreadfuls.” To this day, some of Burns’s surviving siblings deny that their brother was gay (or at least refuse to talk about it).

Mr. Margolick creates the unavoidable impression that Burns’s homosexuality contributed significantly to his becoming an increasingly bitter, biting, sarcastic, and unhappy man, and that there was a direct connection to his drinking — all of which short-circuited his innate talent and diminished his success and his reputation.

On one hand, ultimately all one really needs to know about John Horne Burns is what Hemingway once wrote about him in his characteristically spare manner: “There was a fellow who wrote a fine book and then a stinking book about a prep school and then just blew himself up.”

All the rest is detail.

On the other hand, while Mr. Margolick’s biography does not convince me that Burns deserves the attention it affords him, it does illuminate what it was like to be gay at a particular moment in time. And as society moves toward eliminating what some consider to be the last acceptable prejudice, that is a worthy contribution. (Is it cynical to suspect that the book’s publication was timed to occur during Gay Pride Month?)

Moreover, this book has inspired me to seek out “The Gallery,” if for no other reason than to see what all the short-lived fuss was about, once upon a time.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

David Margolick lives in Sag Harbor.