Marching Anew For Suffrage

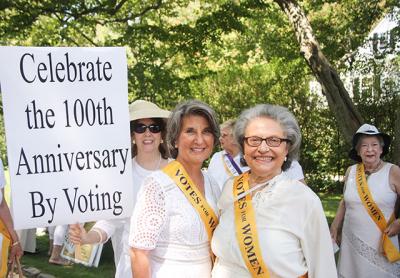

A crowd some 200 strong, mostly women and most wearing white, gathered under the shade of the elms on East Hampton’s Main Street last Thursday to recreate a march for women’s suffrage that took place here in 1913, four years before women gained the right to vote in New York State.

Organized by the League of Women Voters of the Hamptons, the march began at the house where May Groot Manson, a suffragist leader, lived in 1913. The marchers stopped at Clinton Academy, where they were welcomed by Arlene Hinkemeyer, vice president of the league, Jill Malusky, executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society, and David E. Rattray, the editor of The East Hampton Star.

Mr. Rattray pointed to an editorial in The Star that day that called attention to the fact that even as New York celebrates the anniversary of women gaining the right to vote, “the struggle for equal access to the polls continues.”

It was a message echoed by many in the crowd, most of whom wore yellow ribbon sashes bearing the slogan “Votes for Women.” A handful of staffers from the Lady Parts Justice League, a reproductive rights organization, had handmade sashes that drew particular attention to “black suffragists seldom recognized by feminists and often omitted in the history of voting rights activism,” according to a release. Some said “Black Lives Matter,” and one bore Sojourner Tru th’s famous rallying cry, “Ain’t I a Woman?”

Nicole Moore, the organization’s communications director, said some in the crowd seemed taken aback by the message, but, she said in a statement, “It’s imperative for feminists to look at how patriarchy has impacted the women’s movement and how, even in 2017, the voices of black women and women of color are being excluded.”

After stopping at Clinton Academy, in a festive wave of white, the group made its way to the East Hampton Library. There, Lt. Gov. Kathy Hochul talked about what women like Ms. Manson and her predecessors were up against when they began to publicly agitate for access to the ballot box so many decades before that historic local march.

“It was a crime at the time, and you could be arrested for having the audacity to vote for office,” Ms. Hochul said. She recalled “what women had to endure” to gain the right to vote, “how audacious they had to be . . . how bold” to stand up to their communities and even their families. Newspaper accounts and editorials in the wake of the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 were largely unsupportive of the effort, she said. One wondered, for example, if women insisted on voting, “where, gentleman, will be our dinners . . . ?” And anti-suffrage pamphlets pointed out, “You do not need a ballot to clean out your sink spout.”

In 2017, “do we have the same courage, the same fortitude, the same fire to march on?” Ms. Hochul asked. Women’s equality remains elusive today, she pointed out, and then wondered, “What will they say we did” at the bicentennial of women’s right to vote in New York. “Are we doing enough every single day,” she asked, to call out intolerance and inequity?

Ms. Hochul, who is chairwoman of the New York State Women’s Suffrage 100th Anniversary Commemoration Commission, told the crowd, “I leave here with a heart full of joy that all of you cared enough about not just our history, but our future, as well.”

Also speaking at the library was Coline Jenkins, the great-granddaughter of Harriot Stanton Blatch, president of the Women’s Political Union and a speaker at the 1913 march in East Hampton. Ms. Jenkins is also the great-great-granddaughter of the 19th-century suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the president of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton Trust.

“This movement affected 51 percent of the population,” Ms. Jenkins said, and it was so important to women because “if you don’t have the right to vote, you can’t get the rest of your rights. . . . It starts with drops and drops and drops, and they flow into a stream, they flow into a river, they flow into an ocean.”

“We’re all standing on the shoulders of the women and men before us,” she said, and “our shoulders will be the ones that future generations stand on.”

“I’m here today with my mom to commemorate the occasion, but also to bring attention to the fact that voting rights are in danger,” Ms. Jenkins’s daughter, Elizabeth Jenkins-Sahlin, said earlier on the walk from the May Groot Manson house to the library.