The Mast-Head: When There Was No Coal

Coal was in short supply as 1917 came to an end. I did not know this until recently, when I was reading the front page of a copy of The Star that was scanned and digitized by the East Hampton Library.

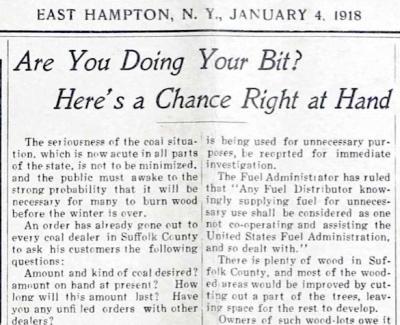

L.E. Terry, the local fuel administrator under a federal wartime program, wrote what amounted to the lead article on the Jan. 4, 1918, issue. In it, he outlined the strict questions that coal dealers had been ordered by Washington to ask each customer to determine if anyone might be hoarding coal. Printed cards would soon be distributed for coal buyers to sign, attesting that they were only ordering enough for their immediate needs.

If conditions persisted, East Hampton residents would soon have to burn wood for heat, Terry wrote. Suffolk County had plenty of that, and wooded areas would benefit from cutting, leaving new growth a chance to spread out. It was, he argued, the patriotic duty of wood-lot owners to cut wood themselves or allow someone else to do so. Owners of wood lots who refused should be reported, he wrote.

Wood lots were an old idea in East Hampton. Most of the families who established footholds here in the 17th century were granted them by the town trustees, acreage not suitable for farming but from which a supply of timber and wood for heat and cooking could be maintained. On old maps, land ownership in Northwest Woods appears in long, narrow blocks; these were the wood lots, though they now are broken up to accommodate houses and driveways, pools, tennis courts, and such.

The 1917-18 coal shortage was the result of a bottleneck in transportation more than a reflection of a drop in mining or soaring demand. Even though coal producers were increasing their output at a remarkable rate, wartime production had placed new demands on the nation’s rail system, making it difficult for all that newly mined coal to get where it had to go. Then, an early season blizzard that brought the Northeast to a standstill crimped the supply further.

Coal and the transportation pinch are thought to be one of the reasons President Wilson decided to nationalize the railroads at the end of December 1917. They would return to private control in 1920.

At the time of the 1917-18 coal crisis, some newspapers speculated that coal’s day would soon end and that a century later, its use would be abandoned. Though that day may still come, and nobody much uses coal to directly heat their house today, coal fuels a large share of the electricity produced today. And most of it is still carried by rail.