The Mast-Head: When Words Mattered

Eighty years ago last month, a boy was born in Eisenach, Germany, in a country already being torn apart as the Nazi Party rose to power. That boy was Karl Egon Heilbrunn, my father-in-law, and the story of his coming into the world, his defiant father, and what happened next is one of the millions of small tales of that terrible time that should not be forgotten.

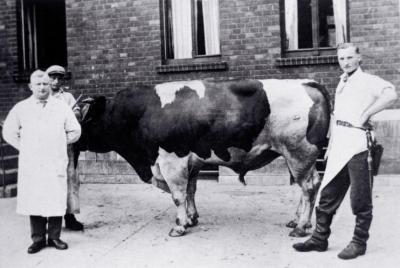

In and of itself Karl’s birth, the second son of Siegfried Heilbrunn, a Jewish butcher, and his wife, Beate, was just another in the small city that once was home to Martin Luther and Bach. In photographs, Siegfried appears to be a tough guy; his family remembers him as a rough character, stocky with thick hands that could quickly take apart the largest steer.

It was he who decided to take out an ad in one of Eisenach’s newspapers, announcing Karl’s birth, and that was not out of the ordinary. What was, however, was that Siegfried Heilbrunn had the paper put the first four letters of his first and last name in bold type. Think about that for a moment: Sieg Heil.

At a time when the Nazis were ascending and had become a force in Eisenach, a Jew had to be brave to do something like this, mocking the party’s own spoken salute. Demonstrations quickly followed outside the butcher shop. Karl’s brother, Martin, then only 3, was sent to the hospital, where his mother was recuperating, with a tall bunch of roses and a butcher knife for her to hide under her pillow.

Word spread, and Julius Streicher, the master propagandist later to be put on trial in Nuremberg and executed for his role in the Nazi war crimes, denounced Siegfried in the pages of Der Strurmer. It was, Streichter said, evidence of “jüdischer Frechheit,” which Martin Heilbrunn translated for me this week as “insolent nastiness.”

That was not the end of it. Germany was soon to be convulsed in one of the greatest human tragedies in history. Whether or not the birth announcement had a direct role in what followed for the Heilbrunns is probably unknown now, but it is clear that the butcher shop came under increased scrutiny.

Martin told me recently that officials eventually went after his father on taxes, and in 1936, when his mother mis-charged a customer a couple of pfennig due to a confusing new regulation, things escalated rapidly. An Eisenach police officer who knew Siegfried warned him of the gathering danger and took him into custody for his own safety. He told Siegfried that he had but 48 hours to get away; if the Gestapo were to detain him, he would have been but 2 hours away from a concentration camp. Siegfried understood that he had to leave Eisenach. He agreed never to return and never to work in Germany again.

Beate remained behind to close the shop and sell the family house, Martin told me. Then the family fled for the United States, ending up in New Jersey in July 1937. Karl, whom I have not said much about so far, and whose first memory is of hiding under a bed while the Nazis entered his house, will celebrate his 80th birthday with family and friends this weekend at home in East Hampton.