In the Maw of the Dragon

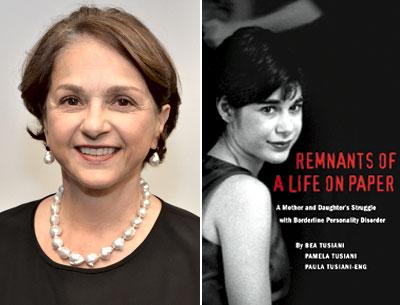

“Remnants of a Life

on Paper”

Bea Tusiani, Pamela Tusiani,

and Paula Tusiani-Eng

Baroque Books, $28.95

“Remnants of a Life on Paper” is a grueling book to read. It is a mother’s account of her daughter’s seemingly inevitable and harrowing slide toward destruction (self and otherwise) and eventually death. On the first page of the book we learn from an excerpt from court testimony that Bea Tusiani, the mother, is being deposed “in a lawsuit you and your husband have against [Road to Recovery] and others in connection with the death of your daughter, Pamela.”

The pall of Pamela’s eventual demise hangs over the book always. Though we do not know of what Pamela will die, the fact of her death is, like an impending storm, darkly threatening, hard to ignore, and ever present.

The book is narrated mostly by Bea looking back over the events of about three years from 1998 through 2001. There are briefer alternating sections by Pamela, in the form of material from her diaries and writings. Occasionally there are more transcript excerpts from various depositions of Bea and her husband, Mike. The Bea sections are matter-of-fact. She is trying mostly for a dispassionate look at the events as they transpired. The sections taken from Pamela’s diaries are sad and often pathetic. She ends many of them begging or thanking God.

Pamela suffers from what comes to be diagnosed as a mix of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and severe depression. BPD is defined by the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders as “a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, and affects, and marked impulsivity that begins by early adulthood. . . .” It is often accompanied by feelings of emptiness and abandonment, suicidal tendencies, self-mutilation, and impulsive use of drugs, sex, and alcohol.

Pamela is an undergrad at Loyola College when she first suffers some kind of breakdown. Her mother finds her sobbing in her dorm room, but she is oddly disconnected and unresponsive. She is admitted to the psych unit at Johns Hopkins and initially diagnosed with an “affective mood disorder,” which, her mother is assured, may be “under control in as little as two weeks.” No such luck.

At first, Pamela is optimistic. “Today was a better day. I just took my medications (all 7 of them!) and was more talkative and involved with activities and attended a group on antidepressant medications, which was very informative. I know I am on a long and difficult road to recovery but at least I am on that road.”

And then a few days later she writes, “I believe I have chronic depression because I’ve always been sad and the medicine will not change that.” She ends this diary entry as she does most of her entries, speaking to God. “God, please help everyone on Meyer 4 [the psych ward] and all the others in the world conquer their depression. I am very scared about the future.”

As a mental health professional, part of what was difficult and punishing for me about reading this book was observing how the medical, psychiatric, and psychotherapeutic professionals involved so often acted so confidently and assertively, and so often were so wrong, misguided, or worse. When Pamela entered the hospital she was on a single antidepressant medication. They immediately put her on “tranquilizers, a mood stabilizer, anti-psychotic and anti-seizure medications. . . .”

The doctors at Johns Hopkins initially put her on nortriptyline, a “mild” antidepressant medication, and when that failed to work after 10 days (not nearly enough time to judge) they suggested electroconvulsive therapy, which is sometimes used to treat intractable major depressive disorder. The problem? No one really knows how that therapy works. It is a bit like smacking your old vacuum tube television to get a better picture. Sometimes it works, sometimes not so much.

At this point, Pamela has entered the maw of the mental health dragon and she is in no shape to defend herself. She begins to deteriorate and to harm herself in various ways: self-cutting, drugging with crack, cocaine, and ecstasy, drinking to excess, and banging her head against the wall. She begins to have suicidal thoughts.

Bea writes, “I’m exhausted. Taking care of Pamela is becoming a 24-hour marathon. Her cutting is so out of control. Yesterday she ‘accidentally’ nicked her arm with a knife in the kitchen, and this morning she slashed herself with a safety razor in the shower. Keeping her from harming herself has become the focus of my every waking moment.”

The doctors soon tell Bea that they are going to try a new antidepressant. “ ‘Once the Effexor kicks in, Pamela will be happier than she’s been in years,’ Dr. Parker assures us.”

Pamela writes, “I’m very confused. I don’t even know what my diagnosis is. So many doctors, so many opinions. Am I chronically depressed or is this just an isolated episode of major depression?” Pamela is now cutting herself frequently with broken shards of glass, plastic, scissors, and even a hair barrette.

Pamela begins a back-and-forth among various psychiatric wards in Baltimore, New York, and Stockbridge, Mass., outpatient treatment programs, and her parents’ home. She becomes so self-destructive and suicidal, however, that Bea and Mike cannot adequately care for her. At one point she drinks a bottle of scouring cleanser.

On top of all this she becomes anorexic and bulimic, too, starving herself or often forcing herself to vomit after eating. “Three months ago, it was drugs, now it’s an eating disorder. When Pamela manages to control one self-abusive behavior another surfaces to take its place.”

After a while, one of the therapists offers Bea for the first time the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. The therapist tells her that it may take “years of intensive therapy to deconstruct [Pamela’s] personality and rebuild it.” And further that there is no medication “prescribed specifically for personality disorders.”

That may be true, but it stops no one from throwing one medication after another at Pamela. Before long she is on a cocktail of medications that would stagger a buffalo: Klonopin, Ativan, Depakote, Prozac, Buspar, Trazodone, Zyprexa. A book that Bea reads on BPD indicates that it may take 10 years for her daughter to get better. “ ‘Ten years?’ Michael says, ‘I don’t think Pamela will make it ten years like this. She’s going crazy and we have to find someone who will help her now.’ ”

And then Bea asks a very astute question: “Is it her brain or her will that is making this happen?” This is, in fact, something that mental health professionals don’t really know. Unlike medical conditions like heart disease or diabetes, there is no definitive test for a diagnosis like BPD. Such diagnoses are based on observation of behaviors, and generally if someone exhibits (as in the case of BPD) at least five out of nine listed behaviors, then they are said to have the disorder. But that is a bit tautological, as such a list is, itself, an artificial creation.

They are told that Pamela needs to be placed in “a closed facility that treats dual diagnosis patients — those with mental illness and substance abuse.” They find Road to Recovery, in Malibu, Calif. It charges $22,000 a month, and once there, they put Pamela on her seventh antidepressant medication. And they add to her already massive medical cocktail Ritalin, Risperdal, Mellaril, Neurontin, Ambien, Restoril, Serzone, and even Thorazine.

Apparently this goes under the strategy that if medications don’t work, try more medications. As if things are not dire enough, once there, she begins to have a frightening series of seizures that are eventually diagnosed as “psychogenic, caused by emotional trauma, not epilepsy.” In an eerie foreshadowing, it turns out that she is faking her seizures.

She is put on Parnate, an early MAOI antidepressant that, Bea is warned, has some severe food interactions. Due to many patient deaths, Parnate had been withdrawn from clinical use in the 1960s and then later reintroduced, but with specific warnings regarding the ingestion of some things like cheeses, wine, and tofu. Apparently, while at the facility that is supposed to be caring for her, Pamela is given pizza (with cheese) and suffers a massive, and this time very real, seizure that leaves her brain-dead.

As a mother’s account of her daughter’s trip through the awful territory of severe BPD, this book is disturbing and upsetting. Toward the end of it, one cannot help but notice a certain amount of ax-grinding regarding Pamela’s treatment at the Road to Recovery facility. It clearly sounds as though she received shoddy care (to be on Parnate and be given cheese pizza is close to manslaughter, to say the least). Further, she was perhaps even on the receiving end of some serious malpractice, but one cannot help but feel that this may be part of why Bea actually wrote the book: to plead her case.

Nonetheless, as a portrait of one family’s and one young woman’s struggles with borderline personality disorder, this is a cautionary tale and perhaps, as Bea writes in her introduction, one that others in similar situations may profit from. “This book is meant to enlighten. The hole Pamela wrote about is still there, but through the telling of valiant struggle, she has extended a hand to help others climb out.”

Michael Z. Jody is a psychotherapist and couples counselor with offices in Amagansett and Manhattan.

Bea Tusiani is the author of a memoir, “Con Amore: A Daughter-in-Law’s Story of Growing Up Italian-American in Bushwick,” and a children’s book, “The Fig Cake Family.” She has contributed “Guestwords” to The Star for many years and lives part time in East Hampton.