Off the Mean Streets

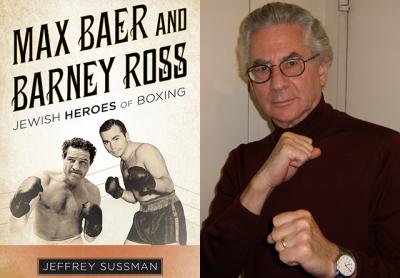

“Max Baer and

Barney Ross”

Jeffrey Sussman

Rowman & Littlefield, $36

Jewish boxers? Somehow, Jews as boxers sounds like a contradiction in terms, or a comical misprint, perhaps a racist joke. Jews, generally, are depicted as a gentle people who would choose to resolve a conflict with wit and tongue rather than with brawn and a right cross.

But this is a flawed reading of history. The bravery and tenacity of the Jewish people, especially as heroic warriors, are renowned throughout the centuries. A sturdy, proud people, their past is well populated with courageous warriors: Moses, Joshua, Samson, Saul, David, the Maccabees, and Bar Kokhba, to name a few.

From ancient times to the present, the fighting spirit of the Jews has been unquestioned. The many Jewish boxing champions and contenders celebrated in Jeffrey Sussman’s “Max Baer and Barney Ross: Jewish Heroes of Boxing” exemplify this great fighting tradition. Jewish dedication, perseverance, and intelligence have set fine examples for those who follow in their footsteps.

When I think of Max Baer, the Jewish heavyweight champion of the 1930s, I think of a man with raw, Tarzan-like strength. In the ring, he was a man of polished muscle, and when he hit you, you stayed hit.

Was Max Baer actually Jewish? Well, you decide. . . .

He was born in Omaha on Feb. 11, 1909, to a Jewish father and a mother of Scots-Irish descent. His family moved first to Colorado and then to California, where he dropped out of school after the eighth grade to work with his father on a cattle ranch.

Max Baer proudly wore the Star of David stitched on his trunks when entering the ring. He was boxing’s most colorful world heavyweight champion until a brash Muhammad Ali rolled around 30 years later.

Baer, a 6-foot-4-inch mountain of muscle and movie-star handsome, could have been such a star instead of a boxer. But Mad Cap Maxie just loved to fight. And fight he did, racking up an impressive knockout streak in California.

As Mr. Sussman points out, Baer had one of the hardest punches in heavyweight history. Early in his career, Frankie Campbell died after his knockout loss to Baer. Years later, the heavyweight Ernie Schaaf died following his defeat to Primo Carnera, but most people say it was Ernie’s savage beating at the hands of Max Baer only a few months before that resulted in his death.

As Mr. Sussman accurately points out, Baer loved to fight, but he loved the nightlife more. He was famous for dancing and drinking the night away with beautiful women instead of training. In 1934, however, the eccentric Max got serious enough to deliver a brutal beating to Primo Carnera to win the world heavyweight title.

Unfortunately, his total disdain for training caused him to lose his title to a 20-to-1 underdog, James Braddock, less than a year later. Mr. Sussman quotes Jack Dempsey regarding Baer’s lackluster performance, staged at Madison Square Garden: “Max Baer’s dilly-dallying and clowning caught up with him in the ring. There was not a dissenting voice raised when the long shot was declared the winner. Braddock won clearly on aggressiveness and clean hitting.”

This battle was popularized in Ron Howard’s 2005 drama, “Cinderella Man,” starring Russell Crowe and Renee Zellweger.

Baer’s next bout was three months later — a controversial knockout loss to the future heavyweight great Joe Louis. Louis gave Baer a horrible beating, and Baer was counted out on one knee. While many experts felt that Baer simply quit, Mr. Sussman sheds additional light on the fight: “At the time, no one knew that Baer had put up a noble fight with a broken hand.”

As is the case with most prizefighters, Baer launched a comeback, going on to shock the experts with an upset knockout victory over a top contender, Tony Galento. But, Mr. Sussman writes, “Baer no longer loved the sport that had elevated him to the status of national celebrity. He was tired of hitting opponents and tired of being hit.”

Baer, at the age of 50, checked in to the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel. Upon his arrival, he experienced chest pains. He called the front desk and asked for a doctor. The desk clerk said a house doctor would be right up.

“A house doctor?” he replied jokingly. “No, dummy, I need a people doctor.” Shortly thereafter, he slumped on his left side, turned blue, and died within a matter of minutes. His last words reportedly were, “Oh God, here I go.”

Mr. Sussman also recounts the exploits of Barney Ross, another Jewish champion.

The word “champion” can be spelled with a small “c” denoting what a man does in a sports arena. Or it can be spelled with a large “C” to cover the things he has done in life. Barney Ross was a Champion who is entitled to the largest capital letter any printer can print.

“Dov-Ber (Beryl) David Rosofsky was a tough little kid. A street fighter. Pugnacious, stubborn, afraid of no one. . . . Beryl, as he was known” before becoming the world lightweight champion, “ran with an informal gang of other teenage delinquents” in “the Jewish ghetto on Maxwell Street in 1920s Chicago. . . . The atmosphere of the Maxwell Street ghetto molded tough young men, for they felt they had to be tough to survive.”

Beryl was a boy weaned on poverty. Furthermore, a “flame of anger” was ignited within him after his father, Isadore, a religious and modest storeowner, was murdered in a robbery.

“While Beryl’s anger boiled inside of him like lava waiting to erupt . . . he could not satisfy his need for revenge. . . . Religion was no longer for him. He gave up attending Hebrew school and never went to synagogue. When his rabbi asked why, Beryl asked what God had done for Isadore, a holy man, a good man gunned down by a pair of lowlife punks who escaped their punishment. Yet, every day, for 11 days, Beryl said the Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer for the dead.”

The street became his “universe and his university,” a place where — with resolve and heartfelt passion — he learned to fight with his fists. Mr. Sussman’s chapter “Fists of Fury” explains how Beryl Rosofsky became Barney Ross, the great lightweight and welterweight champion who staged scintillating performances with other boxing greats: Jimmy McLarnin, Tony Canzoneri, and Hammerin’ Henry Armstrong.

Decades later, Nelson Algren, the author of “The Man With the Golden Arm,” was so smitten with reading about Ross’s illustrious career that he went out and had a pair of boxing gloves tattooed on his arm.

Ross’s boxing afterlife found him enlisting in the U.S. Marines. He won a Silver Star for having saved Marine buddies and killing 22 of the enemy on Guadalcanal despite suffering serious injuries. His addiction to the morphine administered to him during his convalescence, his humiliating slide into addiction, and his subsequent rehabilitation were dramatized in the well-received 1957 film “Monkey on My Back,” starring Cameron Mitchell.

In recounting the exploits of these two fighters, the pages of “Jewish Heroes of Boxing” are full of fascinating cameo appearances by Al Capone, Jack Ruby, Greta Garbo, Jean Harlow, Myrna Loy, Benny Leonard, Abe Attell, Adolf Hitler, Damon Runyon, and Budd Schulberg.

The sport of boxing could surely use another Barney Ross or Max Baer today.

Peter Wood is the author of the books “Confessions of a Fighter” and “A Clenched Fist.” He was a middleweight finalist in the 1971 New York City Golden Gloves and selected to represent America in the Maccabiah Games in Tel Aviv in 1977. He lives in East Hampton.

Jeffrey Sussman lives in Manhattan and East Hampton. He will read from “Max Baer and Barney Ross” at the East Hampton Library on Dec. 3 at 1 p.m.