Meat and Empathy

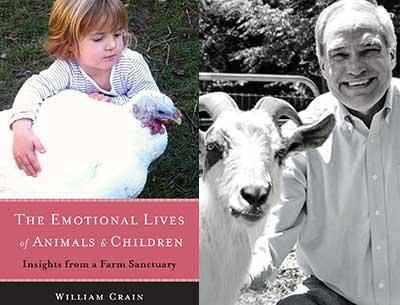

“The Emotional Lives of Animals & Children”

William Crain

Turning Stone, $15.95

William Crain, a professor of psychology at the City College of New York, has written a controversial book, a clear polemic against mistreatment of animals. “If we believe we have a moral obligation to reduce suffering in the world, we must include animals,” he writes. “To ignore their suffering, and focus only on our own species, is self-serving and prejudicial.”

In his mid-30s, Mr. Crain became a vegetarian. He knew little, then, about the horror of meat animals on factory farms. “The thought just came to me,” he writes, “that I would be a more peaceful person if I didn’t eat animals.”

Mr. Crain’s wife, Ellen, a pediatrician, arrived at a similar position. “She decided, pretty much on the basis of facts alone, that the treatment of animals in modern societies was abysmal.” It seemed self-evident that abysmal treatment included the act of eating them.

Mr. Crain hopes to help his readers develop empathy for animals. To accomplish that, he taps into our own childhood experiences with nature, using observations he has made of children and animals at the Safe Haven Farm Sanctuary, which he and his wife founded in Poughquag, N.Y. He admits these are informal observations, not research, yet he makes some convincing arguments that animals and children share many characteristics.

He lists some. 1) Fear. He describes the sanctuary’s first goats rescued from a live meat market. It took them months to develop trust for their new caregivers. 2) Play. He observed a baby goat jumping off a rock, over and over, with variations similar to the behavior of a 3-year-old child who practices jumping off a step. 3) Freedom. The professor observes that free-range animals seem much happier than caged ones, just as children with outdoor space to play in feel happier. 4) The ability to care about others. If treated respectfully by humans, many different animals care deeply for the human species. They can be both loving and protective.

There are times the author strains to make his connections between animals and humans. He hypothesizes that animals share spirituality with humans, but it does not seem self-evident that a goat standing on a hillside gazing into the horizon is in “a state of deep peace” similar to a human meditative state “on a sacred mountain.”

Do the comparisons between animals and children demean humanity? Many great heroes have maintained their own self-worth by differentiating themselves. “I am not an animal,” Spartacus proclaimed. Well, that’s currently open for more discussion, Mr. Spartacus.

The central point seems to be: Children and animals share many qualities. We don’t eat children, and we shouldn’t eat animals either. The author does not take this intellectual leap in writing, but leads his readers to the chasm and gives us the opportunity to jump across it ourselves if we have the tendency to do so. There are times the book’s message is stated so quietly it seems the professor wanted to avoid any controversy the book might engender.

Darwin proposed that all species are related, that we all belong to one extended family. Mr. Crain points out that current animal behavior research finds increasing evidence that other species share human cognitive and emotional capacities. Of all the points the author asks his readers to consider, this may be the most controversial, especially for the world’s religions. If it is possible that all species are related, then religions must pose the question, “Do all creatures possess a soul?” (Or, do any?)

This could be a timely issue for religions to debate, although lessons from history would indicate a discussion would be insufficient to distract some religious people from killing infidels.

The same week I was asked by an editor at The Star to review “The Emotional Lives of Animals & Children,” a headline appeared in The New York Times. “U.S. Research Lab Lets Livestock Suffer in Quest for Profit. Animal Welfare at Risk in Experiments for Meat Industry.”

If there was ever a piece of writing that could help Mr. Crain and others in the animal rights movement reduce animal suffering, this Times article about a taxpayer-financed federal institution called the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center is that piece.

The Meat Animal Research Center is made up of a complex of laboratories and pastures that sprawls over 55 square miles in Nebraska. The center has one overarching mission: help farmers and ranchers produce more beef, pork, and lamb and turn a higher profit. One of the center’s proponents claims, “It’s not a perfect world. We are trying to feed a population that is expanding very rapidly, to nine billion by 2050, and if we are going to feed that population, there are some trade-offs.”

Those trade-offs at the Meat Animal Research Center include baby piglets being crushed by mothers who have been bred to produce larger litters, and dead lambs piled up as mothers abandon one or more of their multiple-birth offspring and the center’s staff allows the lambs to starve in order to see which mothers will respond to the hungry bleating of their rejected babies. This is a disturbing fact for anyone interested in animal rights. Our tax dollars finance research that causes deliberate, extreme animal suffering.

The animal suffering documented in the Times article is more than an isolated incident growing out of a specific need to meet the demands of world hunger. It is the manifestation of the country’s prevailing attitude that the suffering of animals does not matter as long as it is for the benefit of humans. That this is the accepted attitude and practice is evidenced by how animals are treated within the crowded factory farms that raise commercial beef, pork, and poultry for retail outlets.

Mr. Crain, although admitting knowledge about what goes on within the factory farms, has chosen not to inform his readers, assuming, I imagine, that perhaps enough has already been said. On the other hand, it seems anyone who is concerned about animal suffering should not ignore a chance to speak truthfully about the accepted standard of practice on corporate factory farms, a major cause of animal suffering.

It is to their credit that Mr. Crain and his wife fight the pervasive national attitude about animal suffering through the Safe Haven Farm Sanctuary, with its 70 animals they have rescued, some from live meat markets in the Bronx and some that have managed to escape from a neighboring game farm where birds are raised off-premises, shipped to the farm, and released from cages moments before a hunting party arrives to shoot birds that have barely learned to fly. But the live meat markets and the hunting farms are small potatoes in the struggle for animal rights. The cause Mr. Crain promotes is a badly imbalanced fight against a monolithic corporate factory meat industry, supported by the U.S. government, where there are tens of millions of animals in despicable conditions. And these conditions are pretty much ignored by the general populace of the country.

Perhaps Mr. Crain is far ahead of his time. In this country we hardly seem ready to consider the issues of animal suffering and animal rights. In 1949, we participated in and signed the updated Geneva Convention that forbids the torture of human beings. But we now know our country, after an intricate process of rationalization to justify it by the very highest levels of our government, has continued torturing humans. The recently released Senate Intelligence Committee report on torture was reviewed in an issue of The New York Review of Books. The last sentence of the review reads, “We translated our ignorance into their pain. That is the story the Senate report tells.”

One captive was thought to be a high-ranking Al Qaeda member. He was subjected to 180 consecutive hours of sleep deprivation and waterboarded 83 times. It turned out he was not a member of Al Qaeda, but was their travel agent. He had given interrogators all the information he had long before they began using the “enhanced interrogation techniques” adopted by our country.

It is doubtful that the same country is ready to think seriously about reducing the suffering of other species. I’m afraid we will need many more books about animal rights, and many more animal sanctuaries, and many more vegetarians who speak out, and many more small organic farms, and many more elections before animal suffering enters the national consciousness.

Gary Reiswig is the author of “Land Rush,” a new short-story collection, and “The Thousand Mile Stare: One Family’s Journey Through the Struggle and Science of Alzheimer’s.” He lives in Springs.

William Crain, the president of the East Hampton Group for Wildlife, lives part time in Montauk.